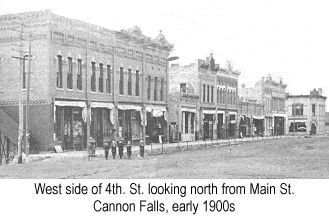

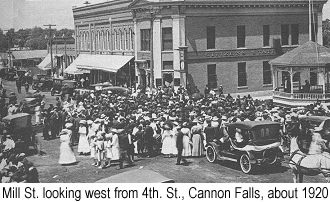

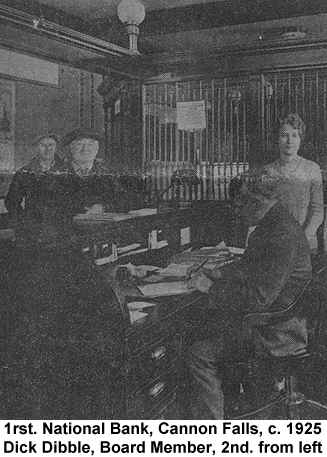

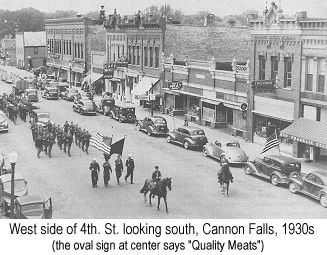

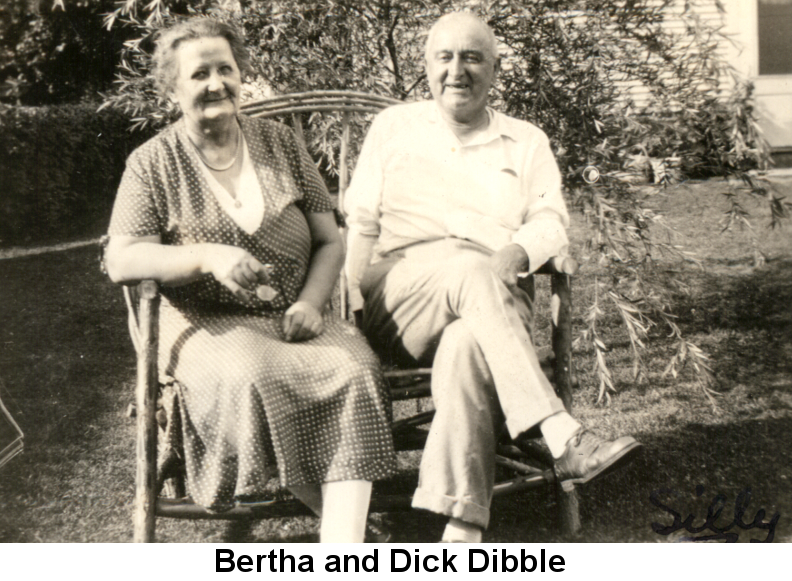

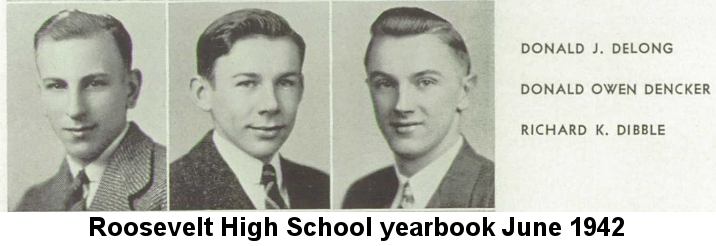

The Dibble Brothers meat market, Dick and Dan Dibble, proprietors, was prospering on 4th. Street. Dick tooled around town in his new 1914 REO five-passenger touring car (REO stood for "Ransom Edward Olds", who had previously founded Oldsmobile). By that year Dick had taken over Dan's 50-something-acre plot in northeast Stanton Township (the land was along the river, whose course periodically wandered, likely changing the size of the plot), and he had also recently acquired a 160-acre parcel of land on Spring Garden Road just southeast of the Cannon Falls city limits. His plan was to start a cattle farm that would provide meat to the butcher shop as well as milk for the local creameries. He had a large stone barn built on the property in the summer of 1915, and a one-story house with a full basement was added that fall. Dick and Dan dissolved their partnership in the late summer of 1916. From that point on, Dick focused on raising prize-winning cattle and maintaining his real estate holdings, including the store building on West Mill St., and Dan continued as sole owner of the meat market.

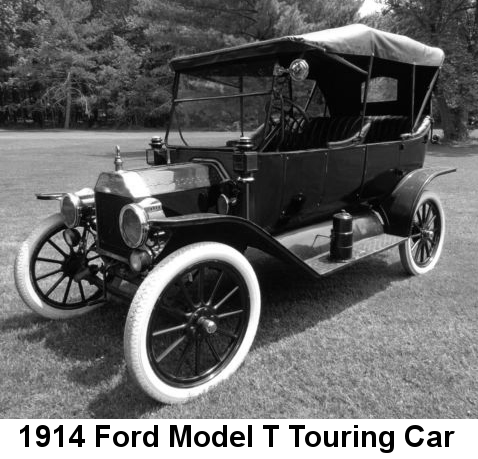

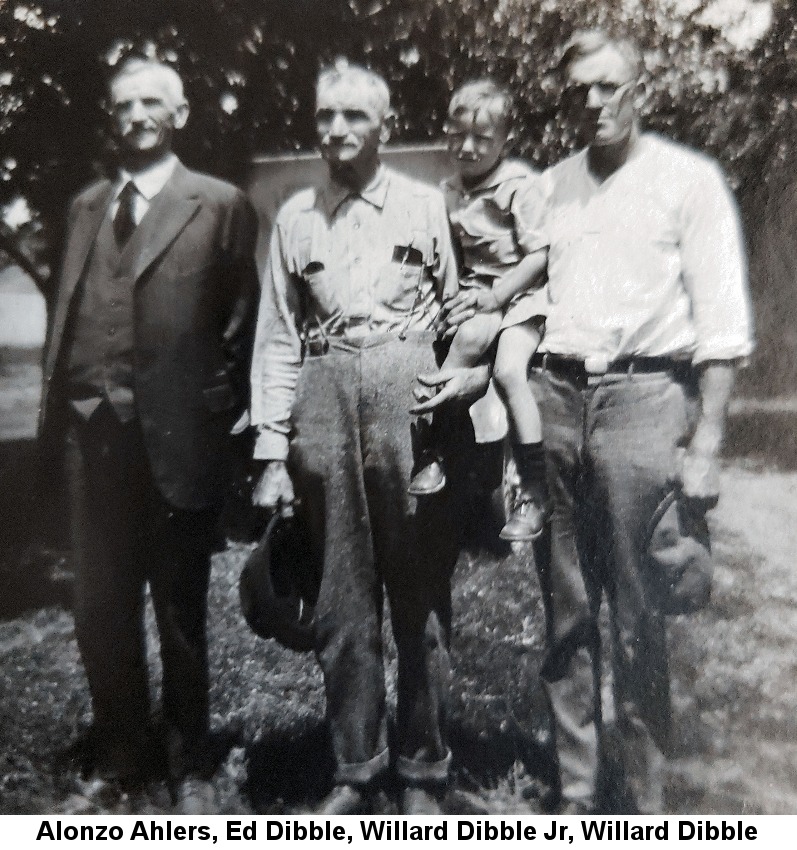

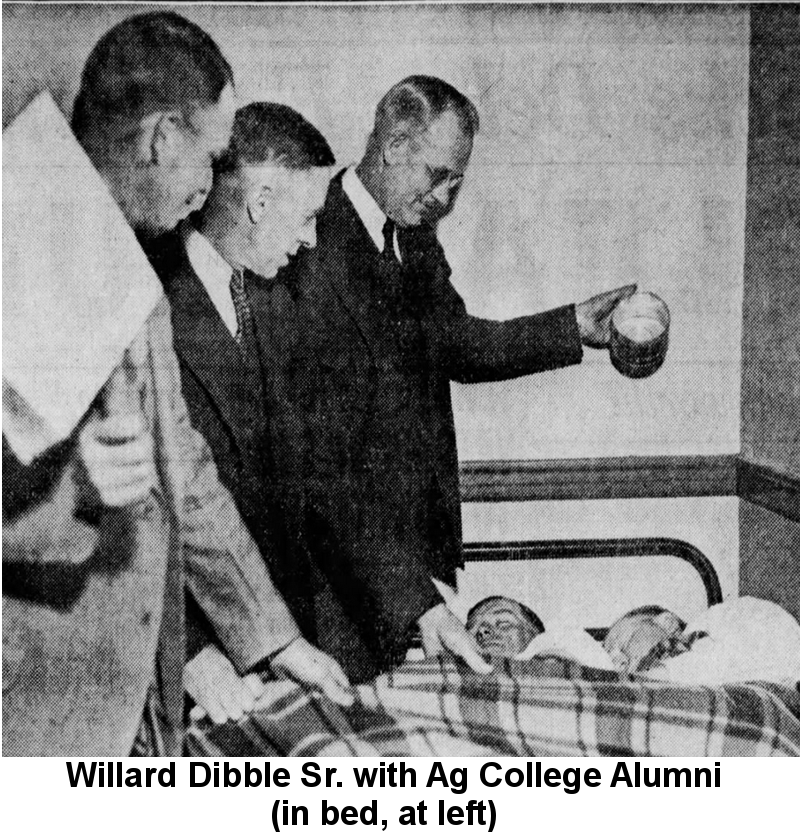

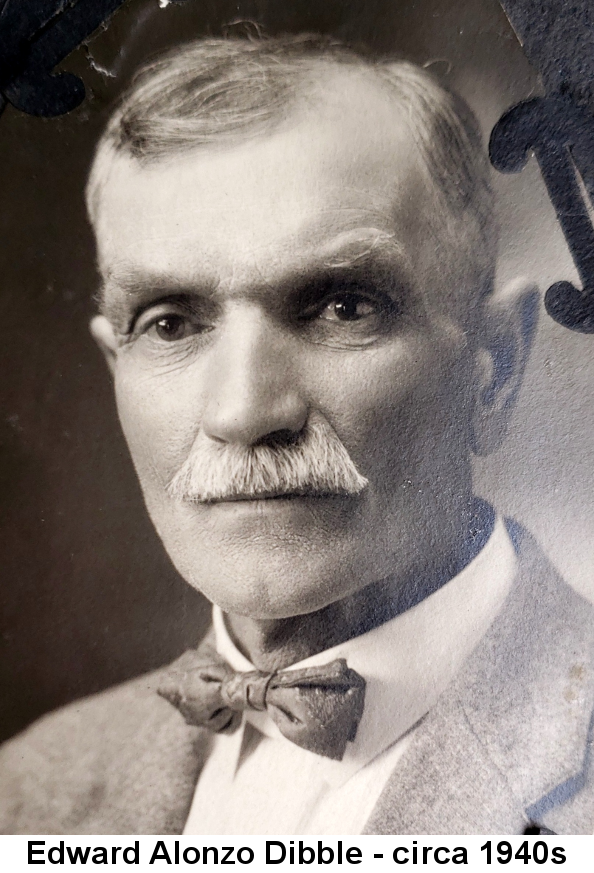

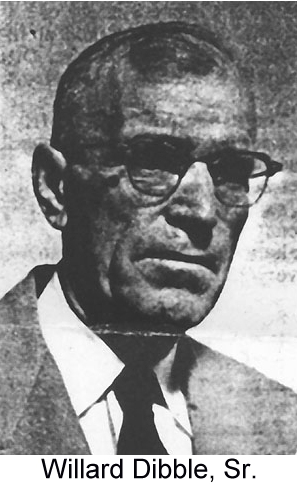

Their cousin Ed Dibble was continuing his political career and was re-elected to the Town of Stanton Board of Supervisors in March 1914. Ed was a local business leader as well; he had been a member of the board of the Cannon Falls Canning Company, along with his brother-in-law Dr. Hiram "Ed" Conley and the town's "summer Santa", Citizens State Bank President Cliff W. Gress, for ten years. Unfortunately the company suffered from increasing difficulties in convincing farmers to grow enough corn to make the operation profitable, and they were unable to attract enough other vegetables to make canning them worthwhile, though they frequently advertised for "any kind of beans". The company changed hands a few times over the next several years, during which Ed left the board. He was elected to the board of the Farmers Shipping and Produce Association in February, and he continued his long history as an officer of the Leon Farmers Mutual Insurance Company, with which he had been associated for at least eight years. He was also still running his 466-acre dairy farm in Stanton, which had recently also begun raising Poland hogs, although his son Willard was about to assume a larger role there. Ed was a Ford man, with a classic Model T touring car (also known as the "tin lizzie").

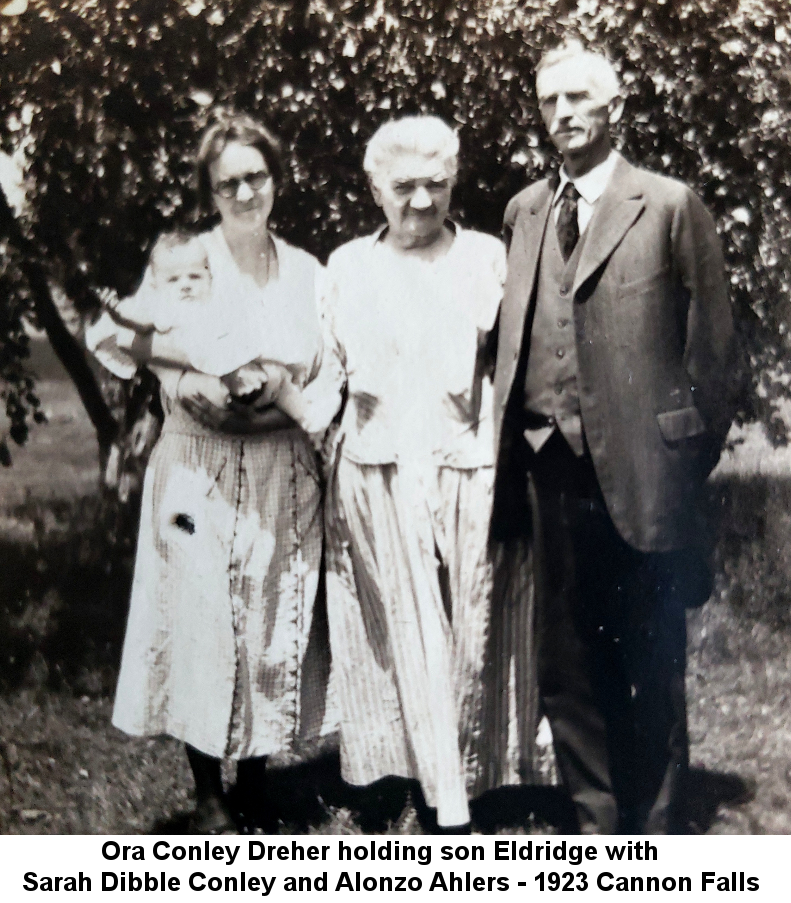

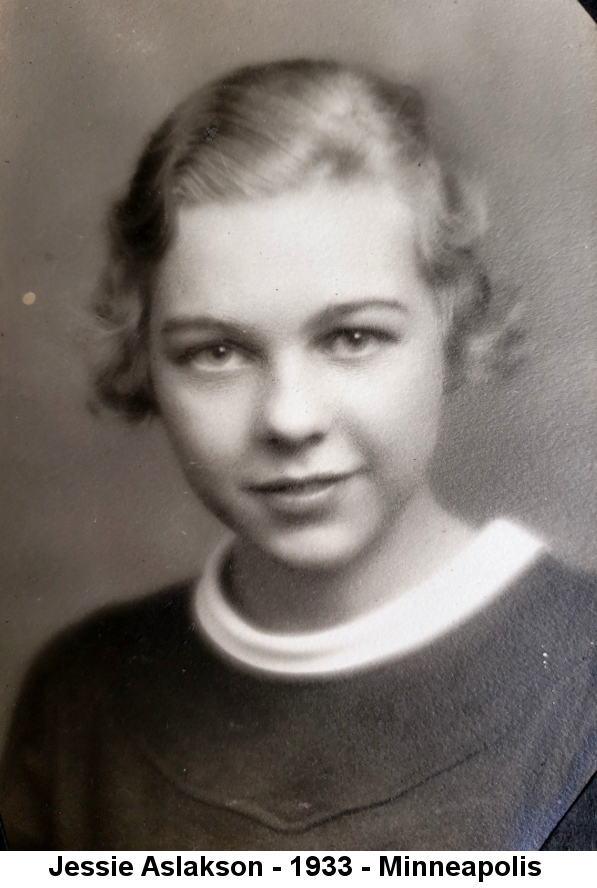

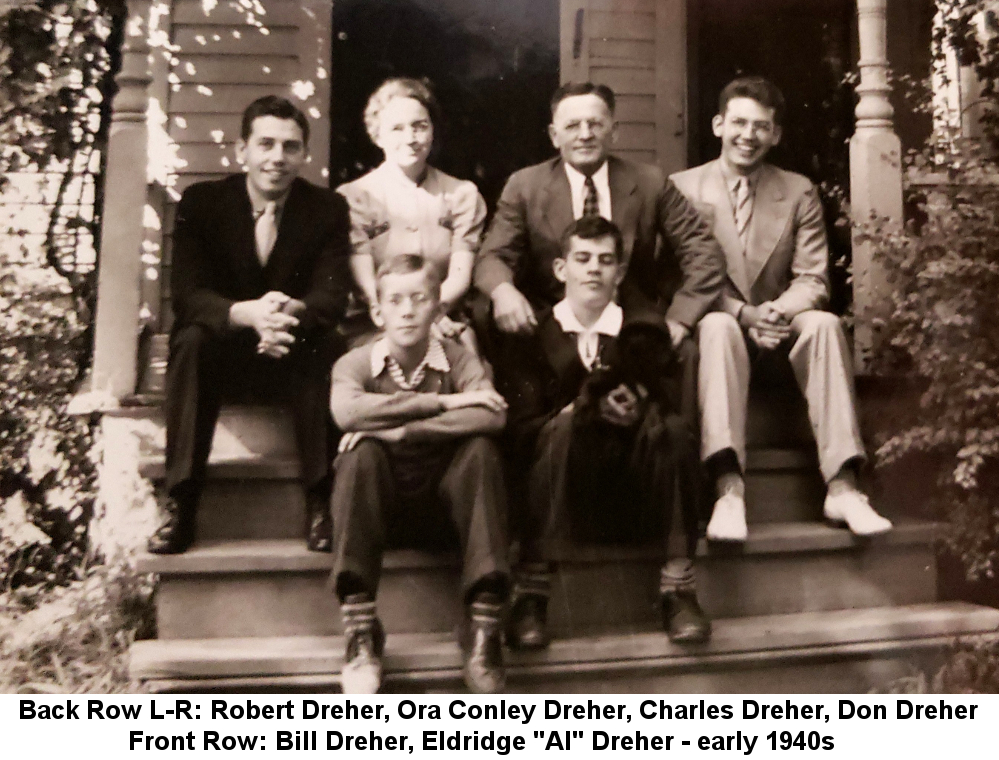

Meanwhile, the younger generation was just getting started. Dick's son Archie was still in business school in Minneapolis, where in January of 1914 he and some other young Cannon Falls men attended a dinner given by Mrs. N. A. Winslow (probably a friend of the furniture-store Danielsons). By the summer he was back home, playing left field for the Cannon Falls amateur baseball team. On July 12 they got drubbed, 10-2, by the Red Wing team: "Peters of Cannon Falls pitched a good game, but poor support at times caused the defeat. The game was interesting and several double plays were pulled off on both sides." Ed's twin sons, Willard and Willis, graduated from the University of Minnesota School of Agriculture at the end of March, 1914. Willis was elected president of the Cannon Falls High School Alumni Association in June. Ed's niece Ora Conley (daughter of Ed's sister Sarah Dibble and "Dr. Ed" Conley), was still in school there. Dan's daughter Jean and her husband the bank teller Milton Holmes ushered their first child, Merlyn Donald Holmes, into the world on April 14, 1914. Dan's son Don played basketball and baseball for the Cannon Falls high school teams. After graduation he went to Faribault, about 15 miles southwest of Cannon Falls on the Cannon River, to work for Consumers Power Company, and he played baseball (as catcher) with his cousin Archie that summer. The big social event of the season was the wedding of Ed's daughter Della to John S. Aslakson, at Ed's home, on June 20, 1914. Willard and Willis were ushers, and John's sister Pearl and Della's cousin Ora Conley were bridesmaids. After a fine wedding dinner, the couple took off for Green Bay, Wisconsin, for their honeymoon.

Almost a week later, on June 26, the often nostalgic Cannon Falls Beacon republished a poem by John Woodman that it had first printed in 1877:

"Hypocrites.

The truth's worst foe is he who claims

To act as God's avenger,

And dreams, beyond his sentry beat,

The crystal walls in danger.

Who sets for heresy his traps

Of verbal quirk and quibble,

And weeds the garden of the Lord

With Satan's borrowed dibble."

Two days after that, on June 28, 1914, Archduke Franz Ferdinand, presumptive heir to the throne of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, and his wife, Duchess Sophie, were assassinated by a Serbian nationalist from Bosnia, a province of the empire. The killings were an unlucky break for the royal family, and would not have happened at all had not the couple's driver made a wrong turn onto a side street in Sarajevo that afternoon. Little notice was taken by the people of the Cannon River valley; the Beacon reported it as merely the latest in a long line of unhappy events suffered by the Emperor, Franz Joseph. Life went on.

On June 5, Dick's nephew (son of his late sister Minnie), Charles Milford Elder, the Annapolis graduate whose adoptive parents took him to live in Georgia, achieved the rank of Lieutenant (junior grade) in the US Navy.

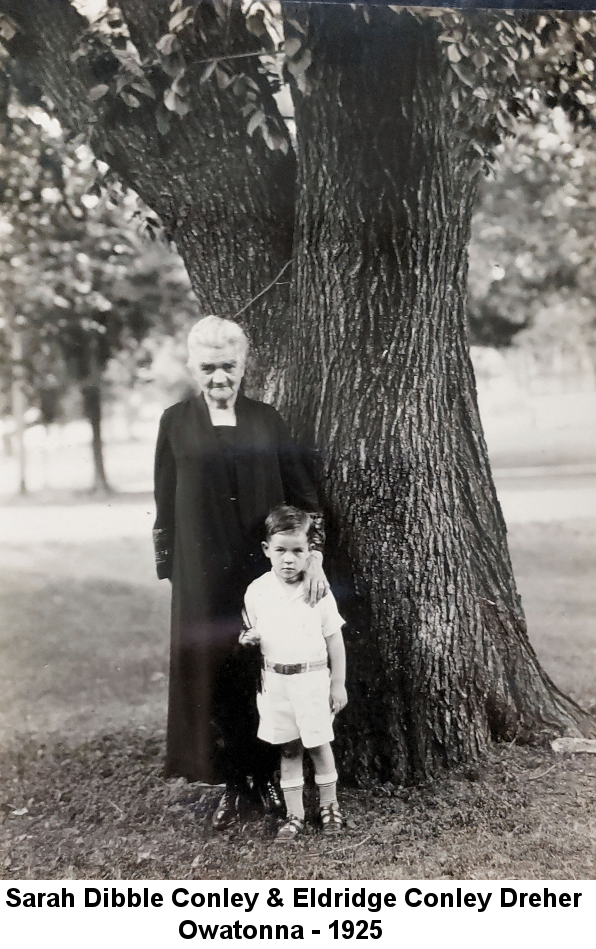

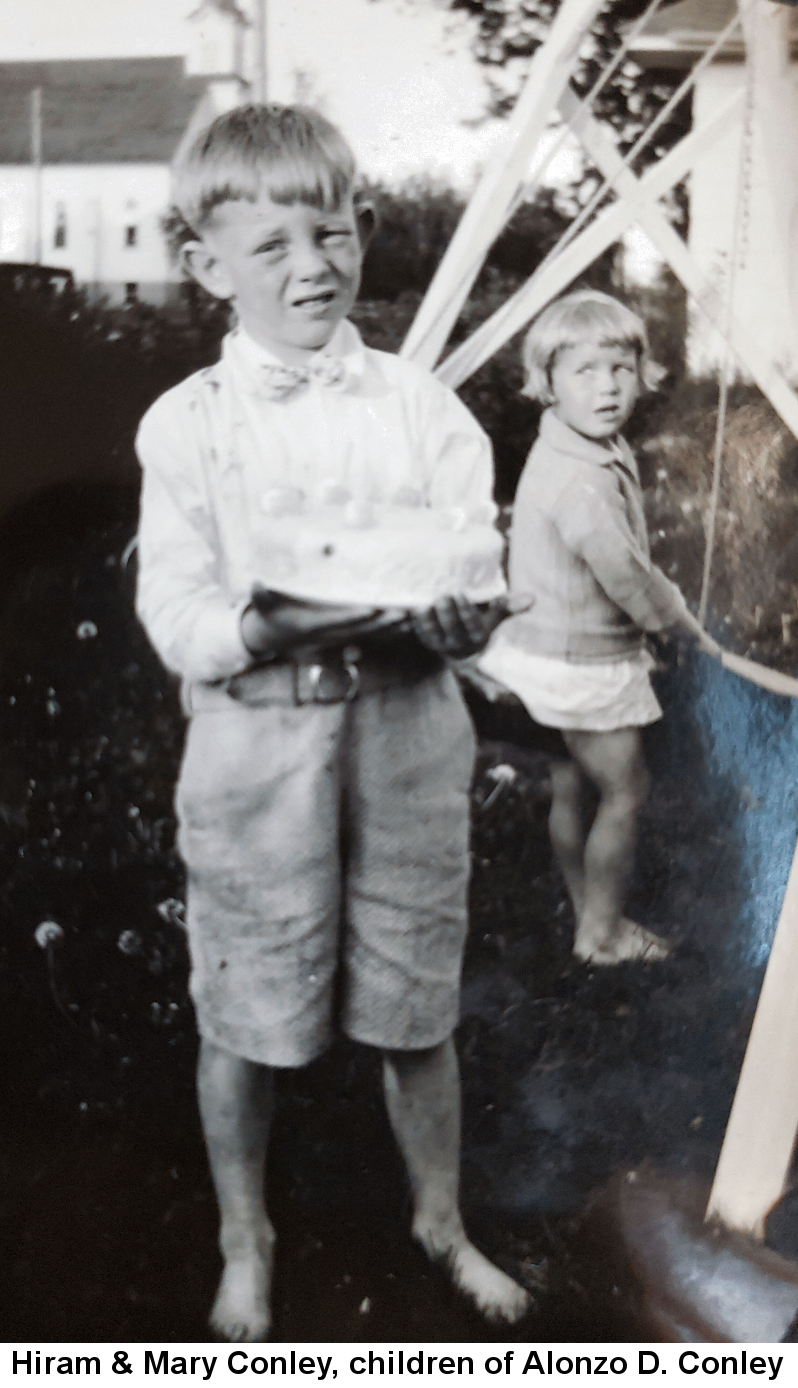

Alva Alonzo Conley, son of Dr. Ed's older brother Dr. Alonzo Theodore ("A. T.") Conley, got his MD from Minnesota State University (although he had already briefly taken over another doctor's practice the previous winter), and he began his own practice in St. Paul. The old man had a grand 67th birthday party near the end of the year, on December 6, at the home of Sarah and Dr. Ed. Many Conley family members attended.

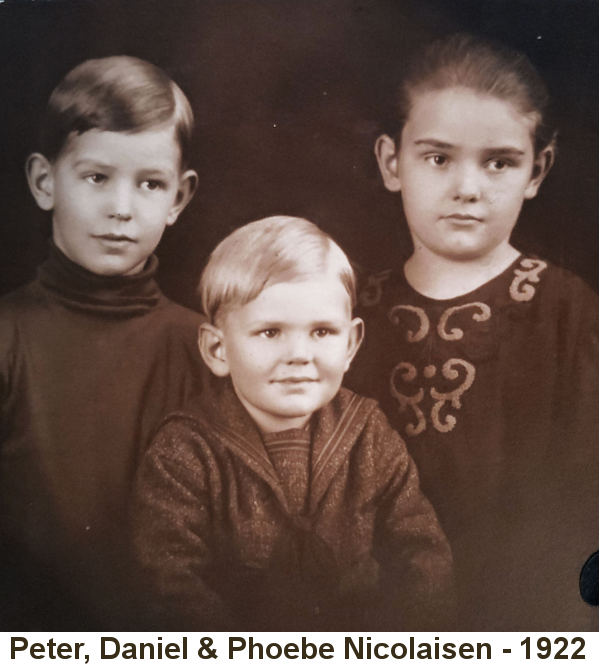

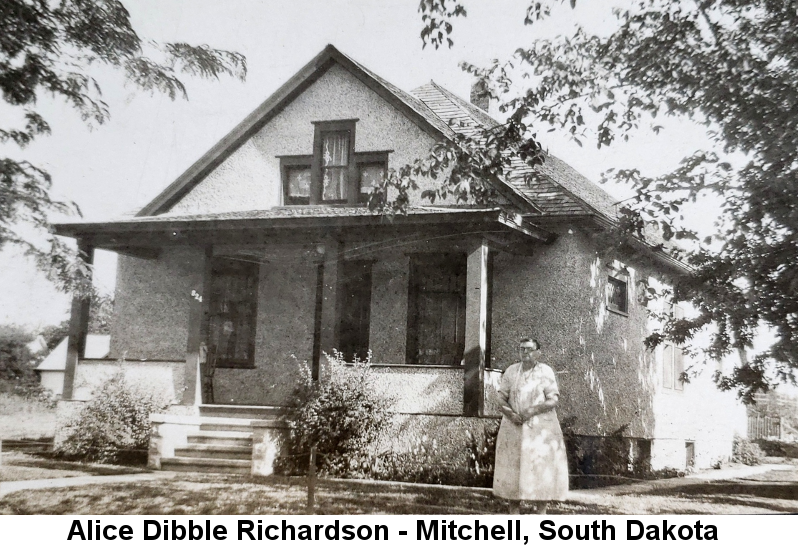

In July, Ora Conley and some of her friends formed a "young ladies club" to meet and discuss important issues of the day. Ed Dibble's niece Cora, daughter of his sister Alice and Frank Richardson, was the editor of the Chicago Herald's children's page. She came to visit friends and family in Cannon Falls later that month. Alice herself had been in town a couple months earlier, visiting from Perkins County, South Dakota on the North Dakota border, with daughter Louise and her husband John Peter Nicolaisen. The couple had married some two years before, in 1912. John, a farmer, was born August 18, 1873 in Iowa to German immigrants Peter Paul Nicolaisen and Kathryn Harkert; he was 21 years older than Louise. They lived near Mount Vernon in Davison County, SD, about 75 miles northwest of Sioux Falls.

So Cora was in town in Cannon Falls on July 23, 1914, when the Austro-Hungarian government, with the support of the German military and diplomats, sent an ultimatum to the Kingdom of Serbia, demanding that Serbia accept an Austro-Hungarian investigation of the Archduke's assassination, including allowing Austrian police to operate in Serbia, as well as requiring Serbia to suppress "anti-Austrian" propaganda and all "terrorist" organizations operating within its borders. Serbia was given 48 hours to reply. Before the deadline expired, the Russian Empire, believing that Germany was using the opportunity to increase its power at the expense of other European nations, decided that it would intervene on the side of Serbia if war erupted. Russia was an ally of Britain and France. French diplomats had by then assured Russia that their alliance included supporting Serbia in a war. But the Russians told the Serbians to accept the ultimatum, perhaps to gain time to complete a planned miltary modernization project. Although historians disagree on some of the details of subsequent events, Serbia's response, though couched in conciliatory language, was perceived by Austria-Hungary as a rejection of the ultimatum.

Austria-Hungary's ally Germany was a multi-party constitutional monarchy with an elected legislature, albeit rather weak. The monarch, the Emperor or "Kaiser", while conveniently portrayed as a monstrous villain in the years to come, was a mostly-ceremonial head of state. The elected head of government, who had the real executive power, was the Chancellor. Kaiser Wilhelm II, an often bellicose first cousin of King George V of England who has been characterized as "insecure", "unstable", "irresponsible" and "reckless" by historians, was not really in charge, and he blew hot and cold as tensions rose. In early July he strongly supported the German ambassador to Austria-Hungary, who pledged German support to that empire "through thick and thin". In late July Serbia, Austria, and Russia (whose Tzar Nicholas II was also a cousin of both King George and Kaiser Wilhelm) mobilized troops, and France began preparing to do the same. But when Kaiser Wilhelm finally got to read Serbia's response to the ultimatum on July 26, he concluded that Serbia had capitulated and there were no grounds for war. He wrote a note to the ambassador proposing that Austria could send an occupying force to the Serbian capital to ensure that the Kingdom kept its promises but should not go to war. He also said he would not support a German military mobilization. This turn-around outraged the Chancellor and the army generals. The Chancellor edited the peaceful overtures out of Wilhelm's note and instructed the ambassador to avoid "giving the impression that we want to hold Austria back." The foreign secretary also instructed the German diplomatic corps to ignore the Kaiser's peace offer, and the minister of War suggested to Wilhelm that the army would stage a coup and replace him with his son the Crown Prince if he didn't drop his peace initiative.

Austria declared war on Serbia on July 28. Diplomatic maneuverings among the other "Great Powers" continued, to try to keep the hostilities confined to those two countries, but the German foreign secretary played both sides of the fence. He falsely told the British ambassador that he was trying to restrain Austria, but when Britain sent a message stating that it would join the war on the side of France and Russia if Germany attacked France, the foreign secretary began backpedaling in earnest. By then it was too late; Austria-Hungary refused to stand down. Germany mobilized and Kaiser Wilhelm switched sides again, expressing his support. By early August, the Great War had begun.

On August 7, the Beacon took the position that while Austria was primarily responsible for the conflagration, there was plenty of blame to go around. An editorialist wrote, "When this crisis came in Europe none of the powerful and influential men maintained their balance. To use a common expression they 'got rattled,' panic stricken, and what at first was a quarrel between Austria and Servia [sic] drifted into a a war involving nearly the whole of Europe. There are men, and many of them, in the humble walks of life who are more capable of acting calmly and thoughtfully than most men in whose hands are placed the destinies of nations."

Fortunately, there were some calm and thoughtful women on the scene. Just a couple of days before the Beacon published its views, Ora Conley's ladies' club held a meeting at which "Miss Alice Lewis read a paper on the present war." However, their calm should not be equated with acquiescence to the circumstances that led to the omission of women from the Beacon's editorial, or from the diplomatic table in Europe: "Miss Alice Smith talked on different women of importance," and "Miss Ora Conley gave a very interesting talk on Mrs. Pankhurst." This was the highly militant British suffragist Emmeline Pankhurst, who by 1914 had been imprisoned at least once, and had taken her organization, the Women's Social and Political Union, in a radical direction, condoning the destruction of property as a means of protest. The activities of Ora's organization might have grown even more "interesting" had it continued, but it seems to have disbanded after a September 5 meeting during which nothing more contentious than card games took place, and Ora returned to college in Minneapolis on September 15.

Meanwhile, Red Wing City Attorney Charles P. Hall, husband of Dick Dibble's first daughter Olive, was raising his public profile. On September 28, he introduced the Democratic candidate for Minnesota governor, Winfield Scott Hammond, at a political meeting in the Red Wing Opera House. In October he delivered an address to a convention of the League of Minnesota Municipalities on "Taxation of Abutting Property for Local Improvements in Minnesota." He favored what he said was a "constitutional provision" that "assessments should be made according to the benefits" that would result to the municipality, rather than following a formula based on street frontage, as was the common practice. But he also called for scheduling days in court before and after assessment proceedings to "give the property owners every chance", and he advocated that the state university produce a model provision for uniform assessment procedures to be used in every city charter in the state. Charles' father, former Democratic Congressman Osee Matson ("O. M.") Hall, must have been proud to see his son operating in a wider political sphere before he passed away on November 26, 1914. He was buried in Oakwood Cemetery in Red Wing.

The year 1914 saw other life-and-death events among the more distant outposts of our families.

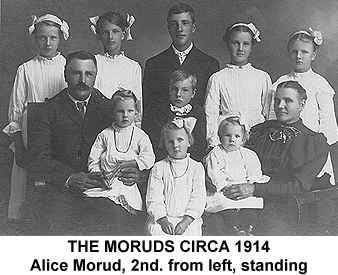

Up in Fergus Falls, Arne Kvern's son Paul and his wife Sena's second child, Alfred Reuben Kvern, was born on May 18 that year. Alfred was the grand-nephew of Anna Marie Kvern Halden and her husband Lars, whose daughter Eline and her husband Ole Morud were busy raising a pack of kids even further north near Warren, MN. Leonard M. Halden, the son of Lars' brother Mathias and his wife Manda, had moved to Big Sandy, MT where the rest of the family now lived, and their daughter, Irene Lavonne Halden, was born there on September 15, 1914.

George Willard Engstrom, a son of Dr. Ed's sister Mary Anastalia Conley and her husband Augustus E. Engstrom, married Ada McLeod (born January 21, 1890) in Blue Earth, Faribault County, Minnesota, about 100 miles southwest of Cannon Falls, on December 18, 1914.

William John Crook, nephew of Ed Dibble's wife Laura, and his wife Hattie M Hine also had a boy child, Clyde Kenneth Crook, born February 7, 1914 in Bozeman, MT.

Dick's brother-in-law Herman Kowitz had moved out to Hysham, on the Yellowstone River in what was then Rosebud County, eastern Montana, earlier in the century, where he and his wife Beda had a 160-acre ranch a few miles south of town along Box Elder Creek. On February 8, 1914, the day after Clyde Crook was born, Herman's mother-in-law Kate (Katherine Trenter) Kowitz, apparently visiting or living with Herman, "died from a fall on ice." In 1912 the county commissioners had proposed to build a new road along the creek between Hysham and Tullock Creek. They did not follow the procedure required by the state for the taking of land for road-building, so Herman staged a nearly two-year legal battle to block the road from crossing his property. He won a permanent restraining order against the county in November 1914. Meanwhile a new board of commissioners was elected and the Billings, MT Weekly Gazette reported, "it is doubtful if the new board will take any action" to start a new, legal process to take the land. However, somebody eventually did build a road between those points (although today there is only an actual Tullock creek, and no town of that name), and Old US Highway 312 and US Interstate 94 seem to follow the proposed route, at least approximately.

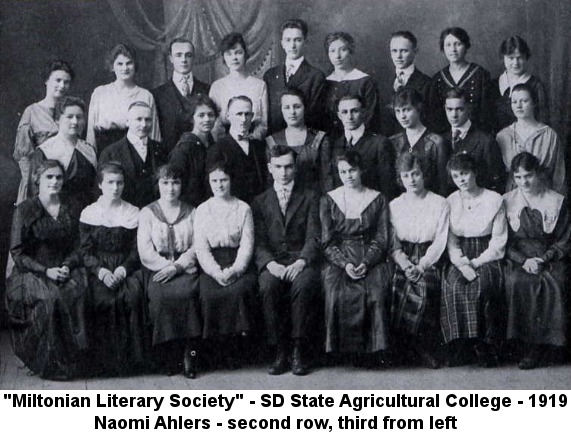

Considerably further east, in Cleveland, North Dakota, on September 24, 1914, Sidney and Evelyn Ahlers had their second child, Roberta Josephine Ahlers. Roberta was a great-niece of Alonzo Dibble's first wife, Louisa Ahlers.

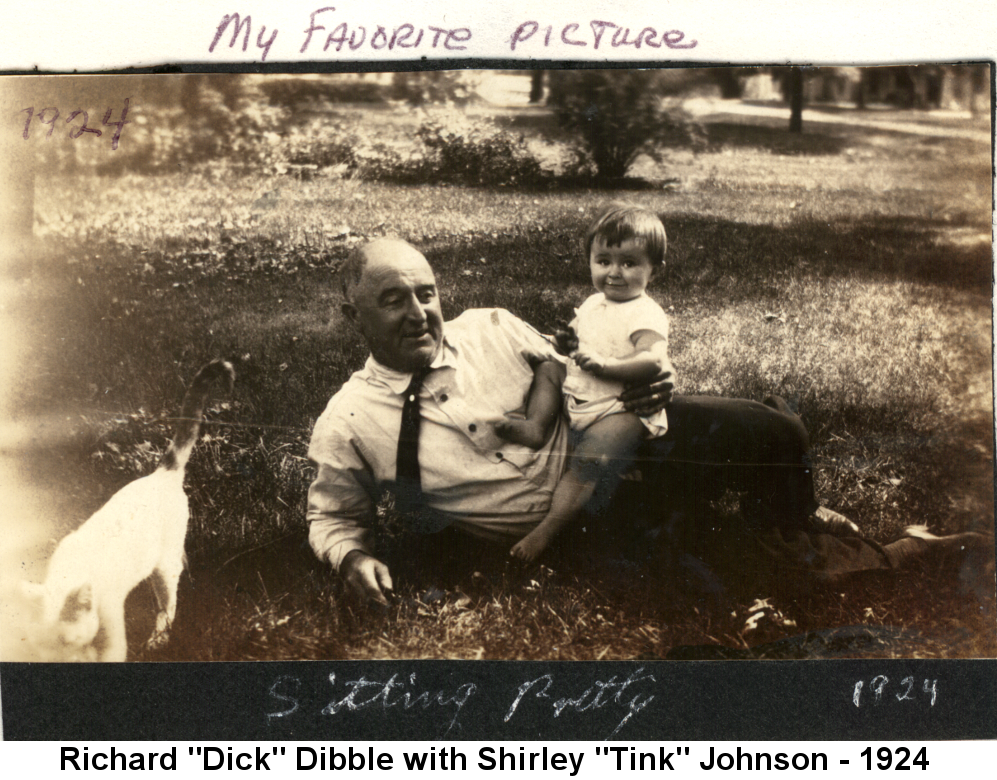

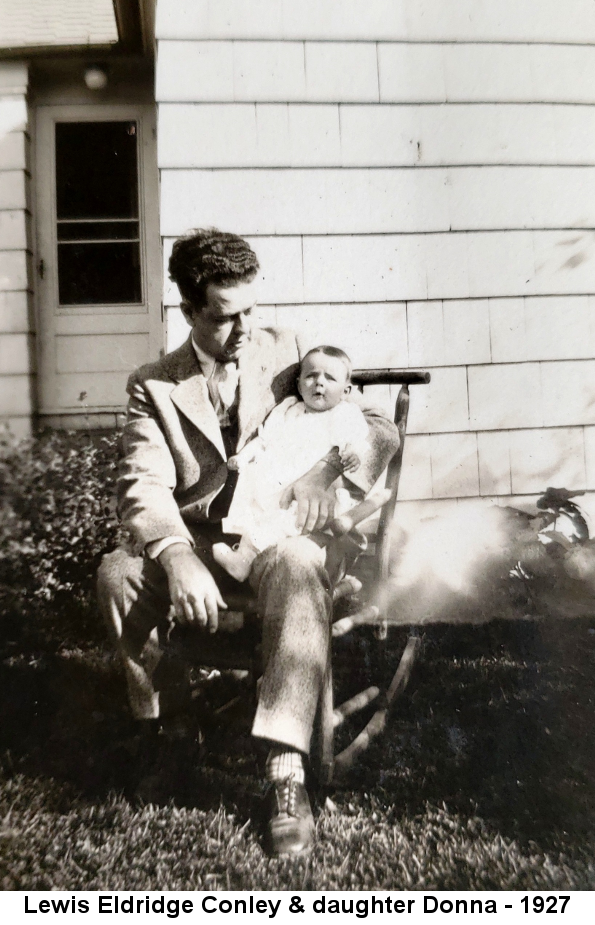

That fall both Don Dibble and Milton Holmes played amateur basketball for the Cannon Falls team. The annual Dick & Bertha Dibble Thanksgiving dinner had a relatively small number of attendees for that tradition, with only 24 people, including Ed and Laura Dibble and their son Willard and daughter Della with her husband John Aslakson, who now lived in Minneapolis; Sarah and Dr. Ed Conley and their daughter "Miss Ora", son Eldridge and son Alonzo D. Conley and his wife Edith; Dick's brother Dan, his wife Isabel, and their son Don and daughter Jean with her husband Milton Holmes; and Dick's daughter Olive Hall.

As the year came to a close, Cannon Falls citizens were thinking about the war in Europe. In early August Germany had invaded Belgium en route to Paris and had installed a particularly cruel occupation regime over most of the country. On December 4, the Beacon urged: "Cannon Falls Should Help the Belgians...All over the country, from farm, village and city, relief is being sent to the suffering people of Belgium. ... Up to this time no action has been taken in Cannon Falls and vicinty but in the name of our common humanity we should delay no longer. The Cannon Valley Milling Company that is building up a large mill here offers to supply flour for the Belgians at cost, or $1.50 a sack. Let us now subscribe for and pay for 200 sacks of flour to begin with before December 15..." These sorts of agricultural relief efforts, just beginning, continued to expand during the war, and they were to have profound economic consequences for rural America in later years.

Dick Dibble's storefront building on Mill Street continued to see turnover in 1915. On January 8, the Beacon reported, "The postoffice has been moved from the Bremer building on the corner of Fourth and Main streets to the central room in the Dibble block on Mill street. The room where the postoffice is located was occupied by C. O. Lundquist, grocer, until leased by the postoffice department. The change is a change without any improvement, and was occasioned, it is understood, by a disagreement between the postoffice department and the owners of the building about the price of rent. The location was satisfactory to the public in every way. But powers that be in Washington decided in favor of a new location." We don't know if Dick's feelings were hurt by Beacon Editor Silas Lewis' characterization of his building, but his pocketbook was not.

Dick's nephew Don was living in Minnepolis that winter. We don't know for sure what he was doing there, but he may have been studying mortuary science at that time.

Don's great-aunt Louisa Ahler Dibble's nephew, Courtney Pearl Ahlers, and his wife Ethel Jilson Walker had a baby boy, Ahlen Leroy Ahlers, born January 22, 1915 near Webster, in Day County, South Dakota. The following month Don's cousin Alice Dibble Richardson saw a new granddaughter's arrival: Phebe Alice Nicolaisen, born to Alice's daughter Louise and her husband John P. Nicolaisen on March 18, 1915.

Dick's nephew-in-law, Milton Holmes, joined the "Cannon Falls male quartette", and a local audience was "greatly pleased with their singing" on April 5. Later that month, Ed Dibble led a discussion on alfalfa at the Stanton Farmers Club, and his wife Laura gave a talk on her successful method of raising chickens in an incubator.

On April 21, 1915, Ed, Past Master of his Masonic lodge, awarded the degree of Master to his twin sons, Willard and Willis. The Beacon remarked that, " It is not probable that such an incident ever took place in Minnesota before."

The next day, April 22, 1915, Johan Peter Johannesson (John Johnson), Swedish patriarch of our Johnson family in Pierce County, Wisconsin, on the other side of the Mississippi, died. He was buried there, in the Clayfield Cemetery near Bay City.

About two weeks later, on May 7, a German submarine torpedoed the British passenger liner Lusitania roughly eleven miles south of the Irish coast, and it sank 18 minutes later. The death toll was 1195 people, including 128 Americans. Although the ship was owned by the Cunard Line, the British government had financed its construction, in return for which it was to be made available for military purposes in time of war. Germany was open about its intent to sink any commercial traffic sailing to or near the British Isles, and it had placed 50 advertisements in American newspapers warning people not to sail on the Lusitania. At the time of its sinking it was an open secret that it was carrying "munitions", though the British denied it. There was a second explosion on board the ship shortly after the torpedo strike, and while it has been speculated that the cause was the ammunition, that portion of the cargo was mostly small arms bullets which aren't really explosive when stored in bulk. There are other theories to explain the second explosion, none of which have been proven, and the torpedo damage was likely enough to sink the ship on its own.

Much of the American media reacted to the sinking with outrage, but all the Beacon had to say about it was published on May 14: "If the State of Georgia persists and executes Leo Frank on no better evidence than that on which he was convicted we can keep our mouths shut about the injustice of sinking the Lusitania." (Frank was a Jewish factory superintendent who was convicted of murdering a 13-year-old employee of his factory named Mary Phagan. His sentence was commuted to life imprisonment about a month after the Beacon article appeared, and in August he was lynched by a mob that included a former governor of Georgia and a future president of the Georgia State Senate.) Elsewhere in the media there were some calls for war, but President Woodrow Wilson said, "There is such a thing as a man being too proud to fight. There is such a thing as a nation being so right that it does not need to convince others by force that it is right." However, behind the scenes he sent three increasingly bellicose notes to the German government, the last of which said that any further such events would be considered "deliberately unfriendly". On September 9, 1915, the Germans announced they would no longer carry out unrestricted warfare on commerical shipping, and would not attack passenger liners at all, and the crisis dissipated--for Americans.

Ora Conley graduated from the University of Minnesota in early June. Her cousin Della Aslakson and husband John had their first, and only, child, Jessie Louise Aslakson on June 20, 1915 in Minneapolis, exactly one year after they were married. Also in June, Ora's cousin George Alonzo Richardson (son of Alice Dibble and Frank Richardson, and Louise's brother), was attending a meeting of the Cannon Falls Alumni Association when something strange happened. He "developed a mental ailment". We don't know what that means, though it may have been a matter of heredity, since his father experienced a similar, though rather more serious, episode about dozen years earlier. Whatever the issue was, it got worse until, back home in Perkins County, South Dakota a couple weeks later in July, he was hauled before the "county board of insanity for examination". Unfortunately, we don't know what the board decided.

On July 16 the Beacon reported that "Oscar Swanson made application for a renewal of his license to operate a shooting gallery for the year beginning July 1, 1915, in [Dick Dibble's] building. Motion that license be granted on condition that all screens and blinds be removed to give a clear view of interior of room from street--carried." We can't even begin to imagine why the city would want to ensure that people on the street could see what was going on in there. In that same issue we learned that Dick's brother Dan sold his house to Harry Hine, whose motorcycle repair shop moved to the basement of Dick's building (accessible from the alley in the rear) a few months later. (Harry's sister Hattie had married Ed Dibble's wife Laura's brother, William John Crook, back in the gay '90s.) This may have been the house near the corner of Hoffman St. W. and 7th. St. N. where Dan was living in 1907. He likely moved to a house on the north side of Colvill St. near the corner of Fourth St. S., not far from where Dick had lived a few years earlier.

That same issue of the Beacon reported that Goodhue County had voted on July 12 to reject the "county option" to go dry--that is, to prohibit the sale of alcoholic beverages. This didn't have as much import as one might think, because nearly all of the towns in the county, including Cannon Falls, had already voted themselves dry. Pine Island, though, reversed itself and became wet; the only other two wet towns were the village of Goodhue and the city of Red Wing.

The Hine family (or "Hines" family; they were known by both names) had another connection to the Dibbles: Laura's sister, Eefluda Crook, was married to Harry's uncle James H. Hine (yes, her name was Eefluda, or, perhaps, Elfleeda; we wouldn't believe it ourselves except that was also Laura's daughter Della's middle name; the Beacon apparently didn't believe it and rendered her as "Alfreda"). On August 15, Laura learned that her sister was gravely ill and she took a train to Fair Oaks, California to visit her. Sadly, she didn't arrive in time; Eefluda died on August 16, 1915. She was in her mid-50s, and her daughter Laura P. Hine and her colorfully-named husband Monte Cristo Freeman (not likely related to the sandwich) had just had a baby six months earlier: Willard James Freeman, born February 3, 1915 .

In September Ora Conley began her career in domestic science by taking a teaching job in that subject at the Sauk Center high school. Sauk Center is about 50 miles southeast of the Haldens' hometown of Fergus Falls.

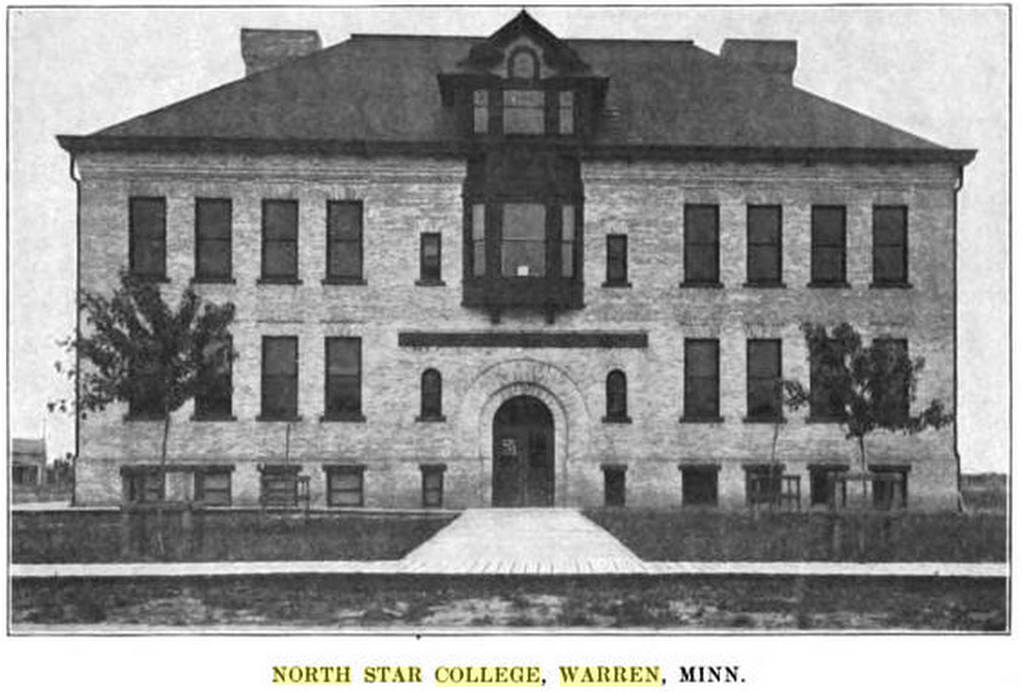

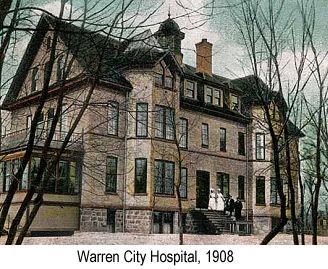

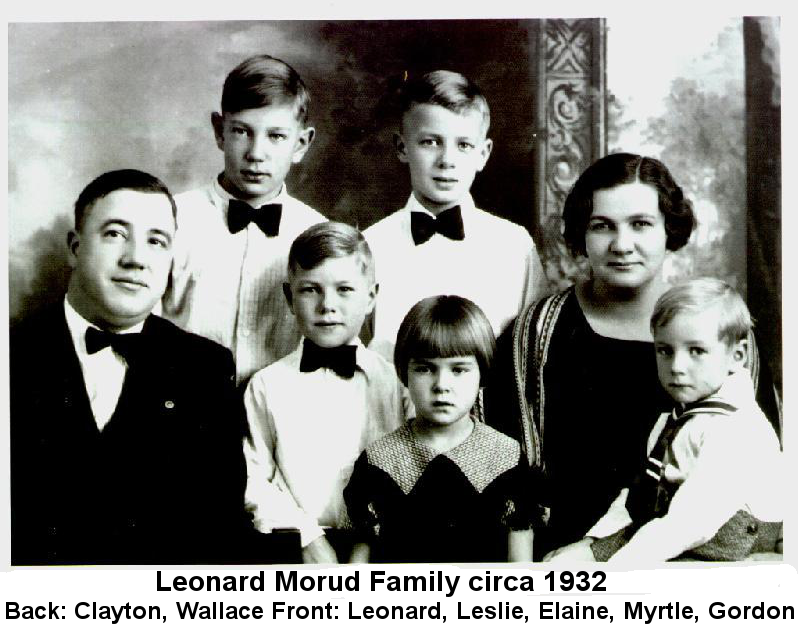

Almost 200 miles north of Ora's new home, the oldest son of Ole Morud and Eline Halden, Leonard, was attending North Star College in Warren. The "college", which was started by the Augustana Synod of the Lutheran Evangelical Church in 1908, actually seems to have been a cross between a high school and a community (what used to be called "junior") college. Leonard pursued the "commercial" course there and graduated, at the age of 17, in May 2015, when he received an award for penmanship from the "Business Journal of New York City". Apparently he was so excited about it that, according to the Warren Sheaf, he "fell off his bicycle on commencement day and dislocated his shoulder. He was immediately brought to the hospital where the joint was replaced. On the following day he was brought to his home by Arthur Willson. On Tuesday he came to Warren on his bicycle. It did not take him long to mend."

While in school Leonard used some of the family acres to grow popcorn, which he sold to pay his tuition. After graduating, he got a job as a bookkeeper for a lumberyard down in Fargo, North Dakota (about 100 miles south of Warren).

Meanwhile Eline's cousin, Emma Louisa Halden, daughter of Eline's uncle Mathias, got married, to Clyde Franklin Knotts on October 5, 1915 in Great Falls, MT. Emma's older sister, Ida, stayed home with her parents and remained single for many years. On the same day that Emma was married, October 5, 1915, Elina's uncle Arne Kvern, her mother Anna's brother, passed away in Fergus Falls. Also in October, a grand-niece of Sarah Dibble Conley was born: Janet Helena Engstrom was born on October 9, 1915 in Hills, Rock County, MN. Janet's parents were Dr. Frederick A. Engstrom and Lilian Rubena Olson. Frederick's mother was Mary Anastalia Conley, a sister of Sarah's husband "Dr. Ed" Conley.

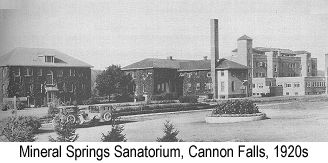

In the early years of the 20th century, tuberculosis was consistently among the top three causes of death in the United States. Public health campaigns against the disease were organized by volunteer organizations, which raised money for education efforts and the construction of sanatoriums, and also advocated for government funding to address the scourge. Health experts thought most tuberculosis infections began in children who were exposed to family members who had the disease, and this was an important reason why isolating adults with TB was favored. We now know that santoriums had little if any effect on the curtailment of the epidemic; reporting of cases to public health authorities and better sanitation, including laws prohibiting shared drinking cups in public places, were more effective. Goodhue County opened its Mineral Springs Sanatorium on November 2, 1915. The facility was located about a mile east of Cannon Falls on the north side of the Cannon River, south of Forest Road near the intersection of 95th. Avenue Way. It had 34 beds for patients, and admission was free to "indigent" county residents; more prosperous residents paid $7.00 a week, and out-of-county patients were charged $10.00 a week. The people of the county were quite proud of this facility.

At some point that same November, Don Dibble moved from Minneapolis to West Concord, in Dodge County, just over the Goodhue County line, about 25 miles south of Cannon Falls. He apparently began working as an undertaker there, perhaps for the West Concord Funeral Chapel.

Also in November, a new member joined Della Dibble Aslakson's extended family. Laura Mathilde Aslakson, sister of Della's husband John, and her husband Edward H. Lidstrand, welcomed Paul Delbert Lidstrand into the world on November 19, 1915.

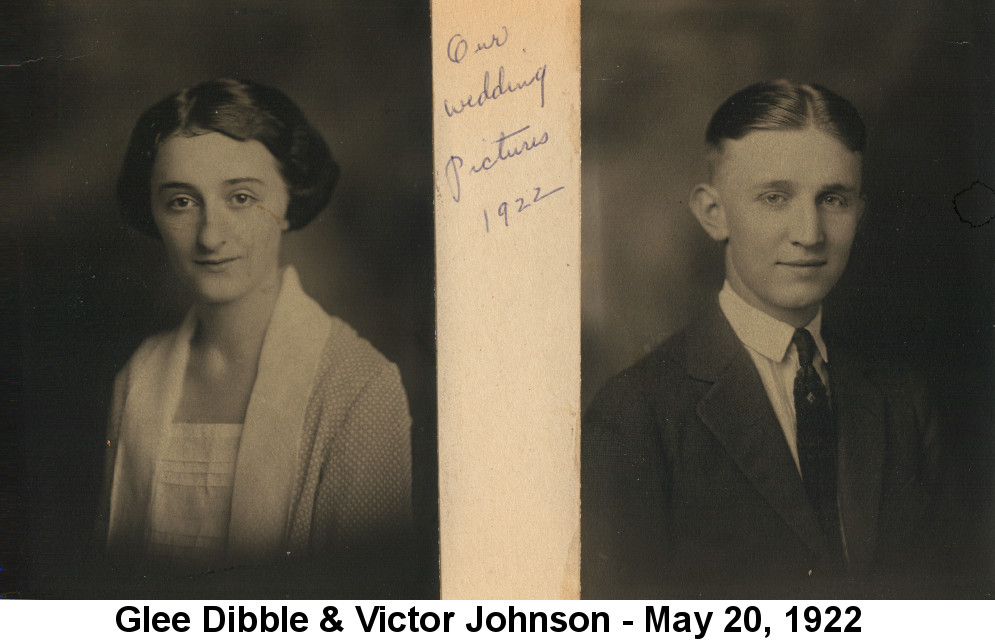

As the year came to a close, Dick Dibble's daughter Glee was elected president of the eighth grade literary society, and she, along with Wilbur Scofield (likely a descendant of his namesake, Wilbur H. Scofield, first teacher at the Dibble School in Stanton Township), was also elected to represent the eighth grade on the "executive council for the ice skating rink." Glee had a small blue velvet-covered autograph book in which several of her friends and relatives wrote little verses and signed their names during her school years. Leona Peters wrote, on July 20, 1913: "Glee:- Think of me long/Think of me ever/Think of the fun we/Have had together." In October of 1917, Eldridge Peters wrote, "The pen is poor,/The ink is pale,/And my hand shakes/like a little dog's tail." At 9 pm on the evening of September 11, 1916, her longtime buddy Frances Thill wrote, "Dear Friend Glee, Always think of me as I think of you," and she signed it "Your Schoolmate". Relatives were a bit less sentimental in their musings. On August 2, 1914, her cousin George "Dode" Wilson wrote: "Glee:- As you stand beside the tub/Think of me before you rub." And, date unknown, Glee's brother Archie inscribed thusly: "Dear Sister Glee, One day as I sat at the table/weary and ill at ease/There suddenly came upon me a/strong desire to sneeze." He credited this little gem to Shakespeare.

Archie, home from business school, was working as a clerk at Scofield Brothers drug store. He was mentioned in a half-page ad for Christmas toys in the Beacon on December 17, 1915, headlined "Santa Claus Headquarters", that told a story of how he had "inadvertently left the door to Noah's Ark open and a large number of the animals had made their escape and at once went to carrying on in high style, evidently bent on having 'a hot time in the old town to night.'" The ad also featured several nasty racist stereotypes, common in those times.

On February 18, 1916, up in Fergus Falls, John Alfred Halden and his wife Ida welcomed a new daughter, Margerie Eleanor Constance Halden. She was a grandchild of Mathias Halden, and so a cousin of Eline Halden Morud. John, a jack-of-all-trades, may have been running a threshing rig for local farmers and also working as a machinist at this time. One month later, on March 18, out in scenic Kalispell, Montana, Eline's brother Alfred and his wife Olga had their second child, Ruth Elida Halden. Alfred worked as a baggage handler for the Great Northern Railroad. Ruth's middle name was the same as her mother's.

George and Ada Engstrom had moved from Blue Earth down to Winona, where he took a job as superintendent of the Jones & Kroeger Co. printing plant, and that is where their son, George McLeod Engstrom, was born, on April 12, 1916. Later that month, on April 22, Alice Dibble Richardson came to visit her brother Ed and sister Sarah in Cannon Falls. By this time Alice was working as a teacher in Ruthton in Pipestone County in the southwest corner of Minnesota, about 50 miles northeast of Sioux Falls and several hundred miles southeast of the Richardson farm in Perkins County, SD. After a few days she went to Chicago, where she stayed with her daughter Zelle, a schoolteacher, and her husband Roy C. Mills, a streetcar motorman.

Dairy production was the main occupation of many of the farmers in southeastern Minnesota in the early 20th. century. The University of Minnesota's School of Agriculture Experimental Station and its Cooperative Extension program undertook several activities to help farmers in those years. Ed Dibble's twins, Willis and Willard, had taken temporary jobs with one of these programs following their graduation, and were involved in testing the milk output of dairy herds in Goodhue County in the late winter and early spring of 1916. The Cannon Falls Cooperative Creamery had been a local institution in Cannon Falls since 1894. Its incorporation papers, though, included a limitation; they would expire on March 9, 1916. So in January of that year, the company was reorganized and renamed the "Farmers Creamery Company of Cannon Falls", with Ed as Secretary and local banker and "summer Santa" Clifford W. Gress as Treasurer. The Beacon happily--not to say cheesily--reported, "The cheese manufactured by this establishment has gained a reputation for excellence throughout the west and northwest and always finds a ready market."

Things were less happy on the southern border of the United States. In early March of 1916, the Mexican revolutionary and bandit Pancho Villa attacked Columbus, New Mexico with about 500 raiders, and they killed 12 US soldiers. President Wilson sent 12,000 troops over the border on March 15 to chase Villa down.

As the attack on Columbus was winding down, on March 9, the Cannon Falls Civic Improvement Club held a meeting featuring a talk on "Preparedness" by Dr. A. T. Conley, Dr. Ed Conley's older brother (the club's president was A.T.'s son, the dentist Samuel L. Conley). As quoted in the Beacon, the elder Conley said, "All the nations of Europe will no doubt after this war is over, find themselves impoverished and will look with envious eyes upon us. The Japanese, for instance, are a very proud people and they insist that we treat their people as we do the people of this nation and this we do not do." (We don't know if the Beacon quoted some of this out of context, but it seems unlikely that the well-educated physician thought that Japan was in Europe.) "Preparedness" was already becoming a topic of discussion throughout the United States as the war raged on in Europe, Africa and the Middle East, and the Mexican border troubles gave it a big boost. Its most extreme form was promoted by former president Teddy Roosevelt, who felt that all the talk of staying out of war was unmanly; he was for a national conscription program. Dr. Conley was more moderate; in his view recruitment of young men by the military was a problem because civilians starting out in the workforce could make two or three times as much money as new soldiers were paid. He proposed that the military offer training in the trades and arts and sciences in return for a three-year enlistment. However, when he began to describe the potential threats the country was facing, his talk seemingly ran off the rails. He suggested that impoverished England and "proud" Japan might ally against us, with Japan coming at the US mainland from the west through the Philippines and Hawaii, and then joining up with the British in western Canada to invade the Pacific Northwest. He also speculated that an equally "envious" France might also get into the act, invade Mexico, and then take Texas and other southwestern states. He said, "These are not idle dreams but only the forebodings of wise men today."

Some individual Americans did not wait for their goverment to act. On April 20, the "Escadrille Americaine" (American Squadron; later known as the Lafayette Escadrille) was formed by American volunteers with the French Air Force. Some Americans joined the Imperial German Flying Corps. Others crossed the Canadian border and signed up with the Canadian Expeditionary Force. Still others joined the French Foreign Legion.

Yet in early 1916 there was an equally strong peace movement in the United States. Industrialist Henry Ford, who believed that capitalism could defeat war by offering stronger incentives for peaceful economic development, organized a "peace ship" that carried anti-war activists to Europe, where he hoped to convince European leaders to convene a peace conference. Most American religious leaders were pacifists, as were the leaders of the women's suffrage movement. Although the cause was later strongly identified with the political left, including labor unions, syndicalists, and socialists, the so-called "old right"--Republicans who didn't like Teddy Roosevelt--were also in favor of keeping the US out of the war.

In May, over in Northfield (about ten miles up the Cannon River from Cannon Falls in neighboring Rice County, and some five miles west of Ed Dibble's farm as the crow flies), there was a showing of the film The Battle Cry of Peace, which tells a story of how the nation's enemies manipulate pacifists to prevent the US government from spending enough money to prepare for war, and as a result the country is invaded and taken over by the enemy. The 1915 film had a bad reputation among peace activists, and a local man, C. A. Ryan, the "secretary of the World Peace Association", had sent out a flyer the week before to organize a boycott of the showing. He claimed he had several city aldermen on board in opposition to the film, but the film's promoters issued a rebuttal in which the aldermen said they had been "misquoted". This became a big topic of discussion around town, and the film drew large crowds two nights in a row, leading the Northfield News to remark sagely, "that the best way to advertise a thing is to oppose it."

Congress began debating how prepared the nation needed to become, and in June reached a compromise between war and peace. The National Defense Act of 1916 was enacted on June 3. It provided for an increase in the standing army to about 200,000 troops and the National Guard to 450,000 over the course of five years. It created the Reserve Officer Training Corps, which offered summer training camps, and increased the size of the army's Aviation Section, providing funds for 375 new airplanes. The Beacon was most impressed with the Act's reduction of the term of service required of an enlisted man before he became eligible for appointment as a Second Lieutenant from two years to one, and with the additional educational opportunities to be provided to those who enlisted, a la the suggestion of A.T. Conley.

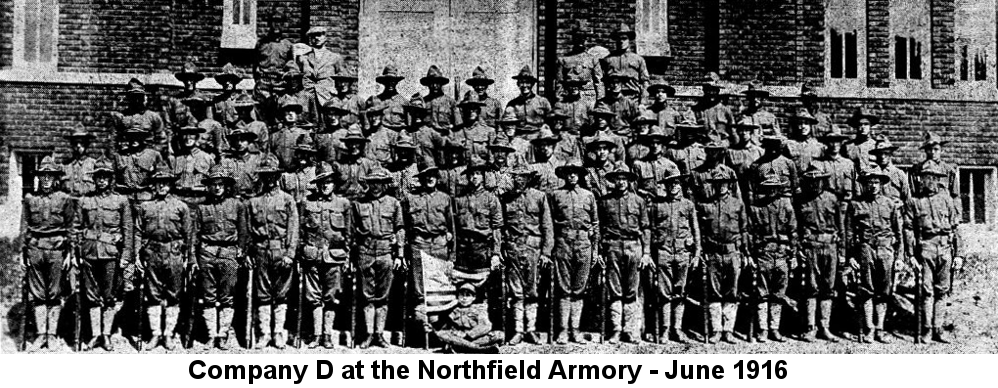

In mid-June the Minnesota National Guard, including Company D of the 2nd. Infantry, Northfield's own, was mustered into the US Army in preparation for service in Mexico. The men of Company D were ordered to report to the armory in Northfield. They were allowed to go home for meals but required to remain in uniform. It was expected that they would soon be ordered up to Ft. Snelling in Minneapolis, which had been preparing to receive an influx of soldiers, to receive training. The company was not up to its full complement of 65 men, so a request for recruits was sent out. Over 50 young men responded, and many more would have but their parents objected. Sure enough, a few days later the company was ordered to report to Ft. Snelling. On the morning of June 26, 1916, the men paraded proudly from the Armory at the corner of Division St. S. and 6th. St. W., crossed the river, and marched north to the depot at 3rd. St. W. and Linden Street, where they boarded a special train that was headed for the fort.

Also at Fort Snelling, with Battery F of the Minnesota 1st. Field Artillery, was Sarah Dibble Conley's nephew, 19-year-old Gordon Charles Curran, a son of Dr. Ed's sister Emma and her husband the Reverend Charles William Curran. Gordon, a student at the University of Minnesota Agricultural College whose family lived in LeSueur about 40 miles west of Cannon Falls, was a frequent visitor to his relatives in the latter city. With him at the fort was Leland Mullen, a brother of Samuel Conley's wife Maude. Samuel and Maude had seen the arrival of their son Kenneth C. Conley just a couple of weeks earlier, on June 13.

The Minnesota boys were sent to the Mexican border in late July to be ready to repel more invasions. As members of the National Guard, they were considered to be "militia", which under federal law could not be sent to fight outside the nation's borders. Gordon wrote two letters to the Beacon from Camp Llano Grande near Mercedes, Texas, about 50 miles west of South Padre Island and five miles north of the Rio Grande, the Mexican border, to describe his work in the camp kitchen, where he cut bread, washed dishes, and performed other "odd jobs". Battery F returned to Fort Snelling by mid-September, apparently without seeing any combat, and Gordon went back to college that fall.

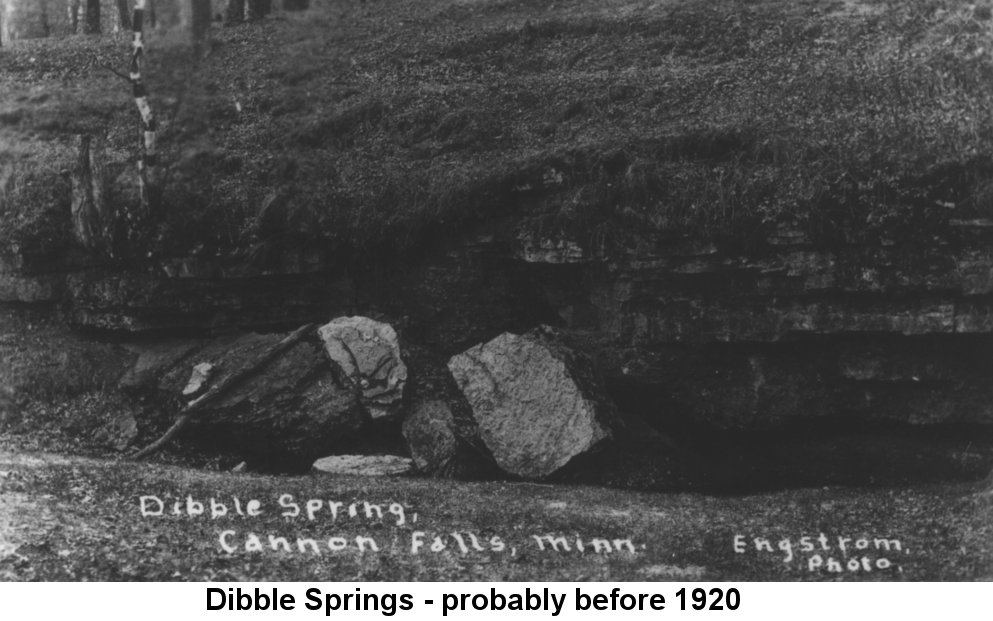

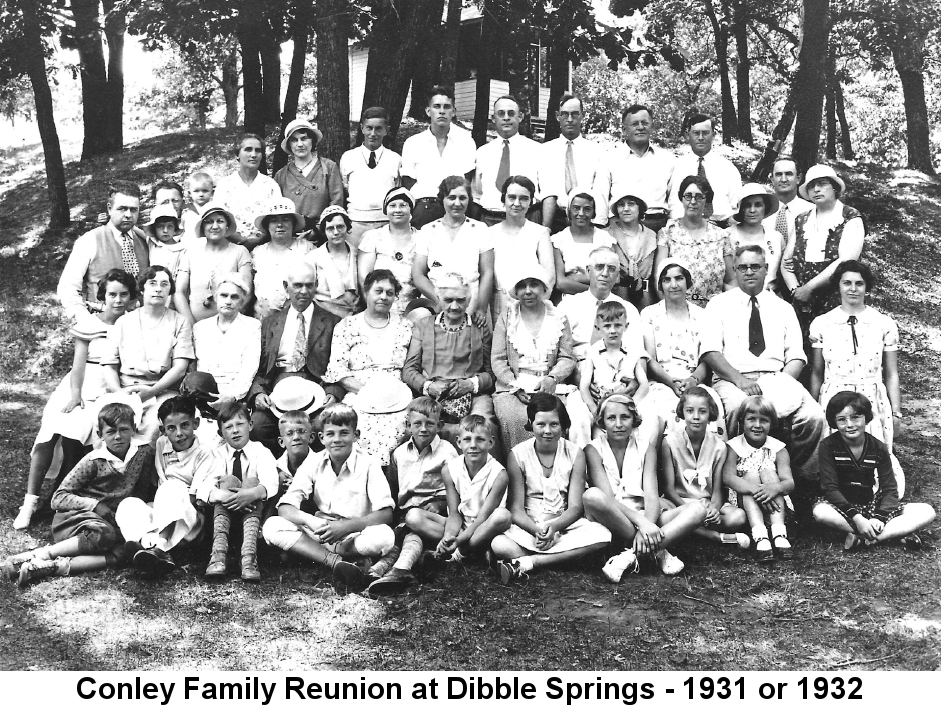

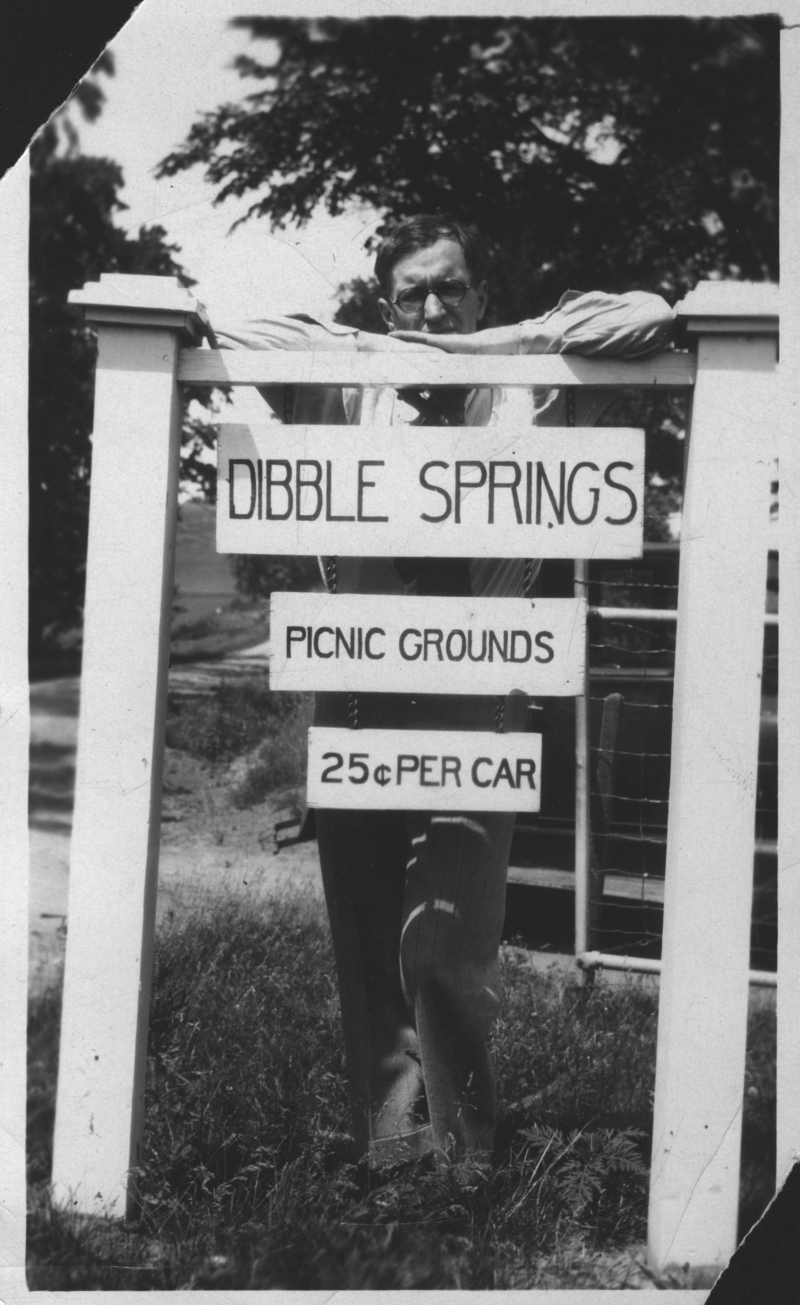

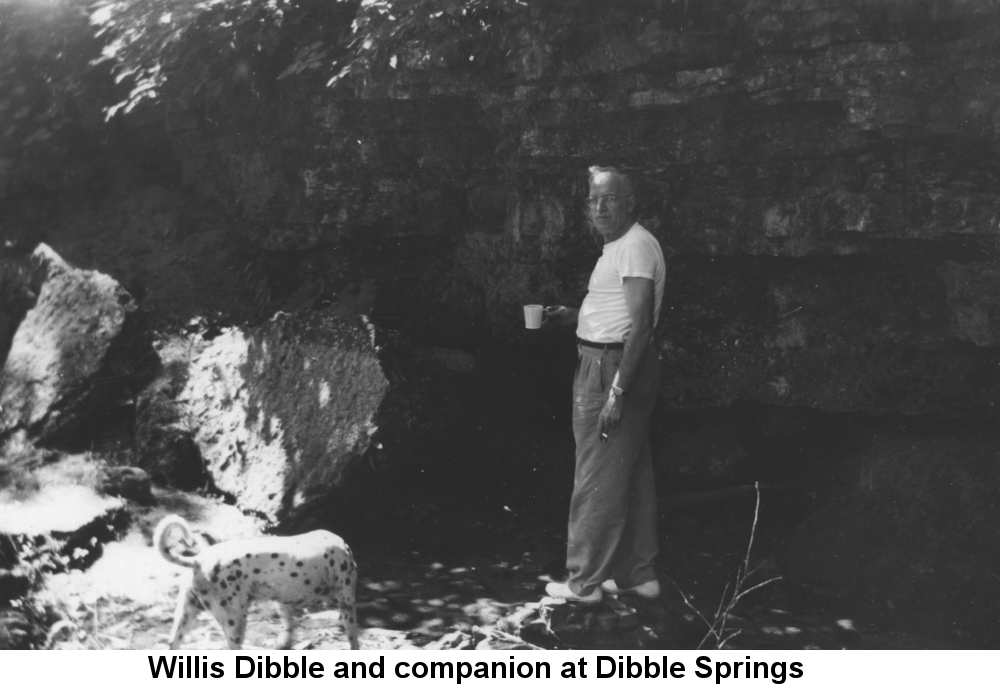

Back in Goodhue County, an idyllic summer was getting underway. Dibble Springs, on Ed Dibble's farm in Stanton Township, had been a frequently used and well-beloved recreation spot for the people of the Cannon River valley since at least the early 1890s. Located along the Little Cannon River, the spot featured a swimming hole and picnic area large enough for school and corporate events. The precise location was just east of what we believe to have been Jonathan Dibble's first homestead cabin, a building that later became the Dibble School. The spring still exists, east of the corner of Stanton Trail and Oxford Mill Road, although the course of the Little Cannon has changed over time, making it unsuitable for picnics today. The spring got its name not long after the Dibbles settled in the 1850s; there's a story that during the Civil War, men from Warsaw Township, just south of Stanton, were receiving military training in the area and "members of this company engaged in a hunt near Dibble Springs when 75 deer were shot." On June 14, 1916, two of Ed's organizations, the Farmers Shipping & Produce Association and the Farmers Creamery Company, held a huge picnic at the Springs, featuring "some of the best speakers of the Northwest", as well as a baseball game between the two companies.

A few weeks later, the Cannon Falls baseball team beat the Nerstrand (about 15 miles southwest of Cannon Falls) nine. The Beacon reported, "Dibble of Cannon Falls [first baseman] was about the busiest man on the diamond and when the game ended he had fourteen put-outs to his credit." He also stole a base. Sadly, we don't know which Dibble this was: Dick's son Archie, his nephew Don, and his cousins Willard and Willis, Ed's twin sons, all played baseball with the high school and local amateur teams of the time. Archie played left field and Don was a catcher, so the game's hero, also featured in other July 1916 baseball games, was probably one of Ed's twins, although we can't rule out a different Dibble entirely; there were other Dibble families located in most of the counties surrounding Goodhue.

That same week, eight young girls established "Camp Linger Longer" at Dibble Springs. The Beacon reported, "The evenings were always spent around a huge camp fire, where everyone enjoyed making candy, popping corn and toasting marshmallows. Cloudy skies did not frighten visitors or campers and the cooks did not put off one breakfast on account of the rain. ...

On Sunday the girls were prepared for company. Misses Irene Carlson and Laura Lockrem spent the day and Wendell Westman, Willis Dibble, Foster and Russell Barlow and Russell Kraft were entertained for supper. In the evening they increased the camp fire circle and entertained a car load of boys. The guests were entertained by vocal selections and Edison records by Bugs, the clown of the bunch, and also by the Linger Longer Comb Orchestra.

Monday night an unbidden prowler was seen around the outskirts of the camp. After he took one of the coziest hammocks, the sentry guard went after the Dibble twins and after a regiment was organized, they searched the woods for all traces of the Mexican bandit. By the bravery of Corporal Bugs, the bandit was almost captured and was court martialed out of camp by a shot gun. ...

The girls also appreciated the kindness of Mr. Dibble for allowing them to pitch their tents near his spring."

Near the end of that month, Ed Dibble's sister Alice, the schoolteacher, returned to town for a few days on her way back from Chicago to Ruthton.

After Dick and Dan Dibble dissolved their partnership on September 1, Dan advertised the business in the Beacon as the City Meat Market, and he sought recognition from former customers: "The meats I handle are Government Inspected and guaranteed to be as represented. A share of the public's patronage is respectfully solicited." The name change seems not to have gone over well though, so by the end of the year his advertisements referred to "The Dibble Meat Market".

In October, Dick's son Archie joined a new 32-piece orchestra in Cannon Falls, where he played second trombone. Archie's little sister Glee was elected president of the Cannon Falls High School freshman class. Glee was also a musician; back in June she had played a piano duet with her friend and rival, Frances Thill, at the eighth grade graduation ceremony. Both of them must have been pretty worried that fall, though, when their father went into the hospital for hernia surgery. He was gone for two weeks, and returned home the Monday before 1916's national election on November 7. We don't know if he voted, or how. We'd guess that his cousin, the local Democratic Party leader Ed Dibble, voted for Wilson, though.

The election was very close. American sympathies for the European Allied Powers, England, France, Russia and Italy, were growing stronger, although many Americans of German descent favored the Central Powers. Left-leaning labor leaders, socialists, and peace activists, who had argued that the United States should stay out of a conflict that was mostly about which colonial empire would have the upper hand in world affairs, were losing the war of ideas. Pancho Villa's invasion of New Mexico had changed many people's thinking: war wasn't just something that happened to decrepit monarchies on the other side of the Atlantic; it had erupted on our own border. And Wilson's invasions and occupations of Haiti in 1915, and of the neighboring Dominican Republic a few months before the election, were still popular with voters. Despite those events and the ongoing military buildup, Woodrow Wilson's opponent, former Supreme Court Justice Charles Evans Hughes, had been effective in criticizing what many still felt was the president's failure to prepare adequately for potential hostilities. Probably the difference in the election was made by Progressive Republicans, former followers of Teddy Roosevelt, who didn't like Hughes' opposition to a recent federal law establishing an eight-hour weekday for interstate railroad workers, or his opposition to the 16th. Amendment, which established the federal income tax.

Yet still, the war only impinged slightly on the concerns of our families at this time. On December 4, 1916, Dick Dibble's nephew Lieutenant (jg) Charles Milford Elder took a position as Aide to the Commandant of the United States Naval Station at Key West, Florida. A few days later his cousins, the twins Willis and Willard Dibble, were once again in their familiar home, on the basketball court, and their team, the Cannon Falls Independents, beat the Minneapolis Beavers. Ora Conley came home too, from Sauk Center, during the winter break to spend the holidays with her parents.

Willis didn't do so well in the first game of 1917; on New Year's Day the Hotel Sherman team from St. Paul clobbered his Independents 42-20. Also that week, Alice Dibble Richardson was back in town visiting her sister Sarah Dibble Conley. Willis and Willard were featured in another Independents loss, this time 33-19, to the South St. Paul Hook 'Em Cows on February 10.

Some of the farmers in Stanton Township had organized a club in November 1916; the club met in the Oxford Church and was known as the Oxford Farmers Club. Willard Dibble was initially the club's treasurer, but by February 1917 he was its secretary. His father Ed was a delegate to a "Federation of Farm Clubs" at that time, though we don't know whether that was a county or state organization. Earlier on the same day that the Hook 'Em Cows slaughtered the Cannon Falls b-ballers, the Oxford club held a big meeting that featured a sumptious noon-time dinner, musical entertainment from the high school orchestra with Maude Conley on the organ, and several interesting talks. Maude's husband, the dentist S. L. Conley, spoke on "Teeth and their Relation to Health", including the "resultant ills of improper mastication." He also said that "a child with bad teeth took six months longer to complete the eight grades than the average child." Willard gave a talk on the "Farm Credit System"; explaining the benefits of the new federally-guaranteed cooperative land bank mortgage loan program.

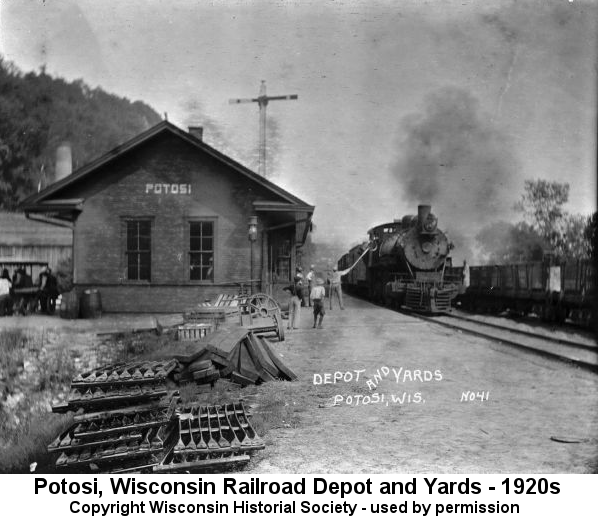

The bank cashier Milton Emmons Holmes took a job with a new branch of the American National Bank that was being opened in Forsyth, Montana, about 25 miles east of Herman Kowitz's ranch in Hysham, and on February 16 he and his wife Jean Dibble Holmes boarded the train for the journey to their new home.

At the beginning of March it had been six months since Jean's father Dan Dibble and his brother Dick disbanded their partnership, and the old company had still not been paid everthing it was owed. On March 2, the Beacon carried this stern announcement: "Final Notice: All accounts due the late firm of Dibble Bros., if not paid before March 15, 1917, will be placed for collections together with interest on the accounts."

Meanwhile, some other accounts were coming due on the world stage.

By late December of 1916, the British had successfully blockaded most of the German navy in its home port of Kiel, and their blockade of German commercial shipping was causing critical food shortages. The German military leadership had been growing increasingly concerned about American preparedness activities, and feared that a US intervention in the war would massively increase the Allied Powers' already considerable advantage in numbers of troops on the ground. A study completed earlier in the year had suggested that if Germany could sink 600,000 tons of commercial shipping per month, Britain would have to come to the bargaining table in six months--well before the Americans would be able to send over a large force. Germany therefore announced its intention to resume unrestricted submarine warfare on January 31, 1917.

This was a bad miscalculation on their part, but their worst mistake, unknown at the time, had already been made. On February 1, 1917, President Wilson cut off all diplomatic relations with the German Empire.

A few days earlier, the US Army, having failed to find Pancho Villa, gave up trying. General John J. Pershing, who had commanded the expedition, withdrew his troops to the place where the trouble began, Columbus, New Mexico. However, this had not been the only recent hostilities between the United States and its southern neighbor. Back in April of 1914, some US sailors from a ship in the harbor at Tampico had gone on an errand in a whaleboat to pick up some fuel oil, and were arrested by the Mexican authorities. Relations between the US and Mexico had already deteriorated in the wake of a 1913 coup that replaced a fragile government of democratic reformers--themselves installed in the first phase of the long-running Mexican Revolution--with a dictator. The coup had been engineered by a rogue US ambassador, whom an appalled President Wilson immediately fired, but the damage was done. In Tampico, tempers flared, communication got tangled, and an American admiral on the scene demanded that the Mexicans disavow the arrests, hoist an American flag on the shore, and give it a 21-gun salute--or else the US Navy would attack. This demand was refused. The situation then escalated to the point at which President Wilson ordered the Navy and Marines to invade and occupy the Mexican city of Veracruz for seven months.

Historians have said that the resulting bad feelings between the United States and Mexico were a primary reason why Mexico chose to remain neutral in World War I. It also seems to have been one of the reasons why the German government thought it could enlist Mexico as an ally. On January 17, 1917, a German diplomat named Zimmerman sent a cable to the German ambassador to Mexico, proposing an alliance in the hope of tying up American resources in a war with that nation. If the United States declared war on Germany, the message said, Germany would provide financial assistance to Mexico for an invasion of the US to reclaim its former territory in Texas, New Mexico and Arizona. The British having cut Germany's direct trans-atlantic cables, the message had to pass over a series of relays and through a station at Land's End in the extreme southwest of England, before reaching the German embassy in Washington, where it was re-transmitted to Mexico. The British were monitoring all cable traffic through Land's End, and they picked up the message. They finished decoding it about a month later and passed it to the Americans. Wilson released it to the press on March 1, and Zimmerman admitted it was genuine on March 3.

On March 2 the Beacon took its stand: "From all appearances it is now time that the American people should be aroused to the dangers of actual warfare. No declaration of war has yet been made openly, but the intrigues and acts of the German government are sufficient to bring on war at any moment. In common with all neutrals Americans have been ruthlessly murdered by the direct order of the German government. No sane man doubts this unless he be a German sympathizer. The time is rapidly approaching from all indications when all American citizens must be known as patriots or traitors. Call the roll and stand by President Wilson."

The Mexican government seriously considered accepting the German offer, but after some investigation concluded that it lacked the capability to successfully invade its northern neighbor, and also that the Germans could not be trusted to come through with the promised funds.

Meanwhile the Germans had sunk ten American merchant vessels since the resumption of unlimited submarine warfare, and although isolationists in Congress were still trying to block Wilson's effort to arm merchant ships, the public was outraged. Wilson asked Congress for a declaration of war on April 2, and it was issued on April 6, 1917.

US military planners believed that an army of at least 1 million men would be needed to fight the war. The National Defense Act did not envision such a huge increase, but President Wilson hoped that patriotic Americans would be stirred to volunteer for service. He was mistaken; despite constant drum-beating in the press, by mid-May, only about 73,000 men had enlisted. Forced conscription was deemed necessary, and on May 18 the Selective Service Act of 1917 became law. It called for drafting men between the ages of 21 and 31 initially (ultimately there were three rounds of the World War I draft). Every man who was not a resident "alien enemy", or who wasn't already in the military (including the National Guard) between those ages was required to register, though they could claim exemption from service on various grounds. Any exemption claim would have to be supported by quite a bit of information and affidavits from the people involved. The draft board would then review this information and decide whether to reject all claims, place the man into one of three different "temporary deferment" classes ("temporary" meant the man would not be called for service until all members of the non-exempt class were inducted), or into the "permanently discharged" class.

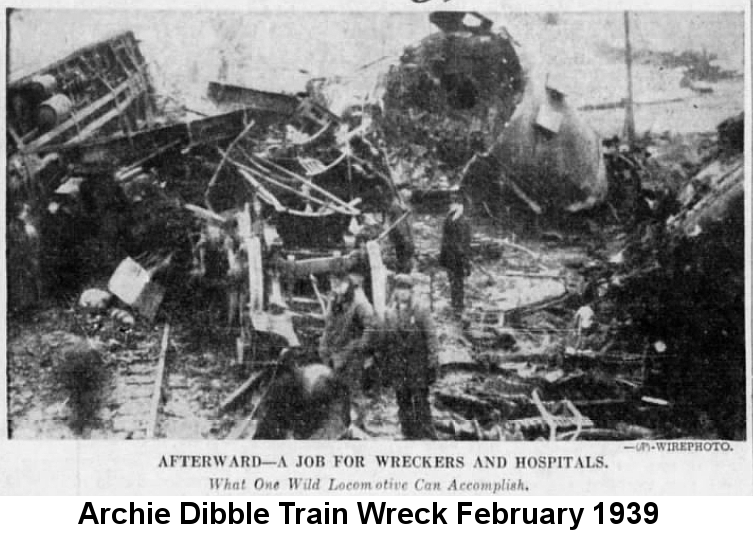

We've found draft cards from this first round for several members of our cast of characters, but not for all of them. Having a draft card, of course, did not mean the man participated in the war, and not having a card doesn't mean he did not participate. For example, we have no card for Archie Dibble, who certainly did serve in the war. We also don't have access to the local draft board records of how they processed requests for exemptions, but we do know that nationwide, almost 78% of those requests were granted. We have not found many details of service for most of our relatives who did serve, and it seems likely that some served for whom we have no information at all.

Draftees for the first round were required to show up at the nearest local board on June 5, 1917 to register and fill out detailed questionnaires. The venerable Peter S. Aslakson, and Olive Dibble's husband and Red Wing City Attorney Charles P. Hall, served as Associate members of the Goodhue County Legal Advisory Board, where their job was to advise county residents on how to complete those questionnaires. Members of our families who registered on that day included:

John Selmer Aslakson, the husband of Ed Dibble's daughter Della, claimed an exemption but didn't give a reason.

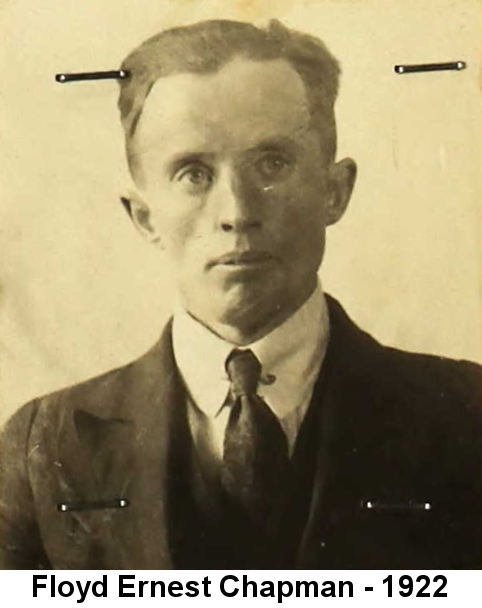

Floyd Ernest Chapman, a son of Edward A Chapman, whose aunt Rebecca Chapman was Alonzo Dibble's second wife, was working as a laborer on his father's farm near Redwood Falls, about 80 miles southwest of Minneapolis. He was single and claimed no exemptions.

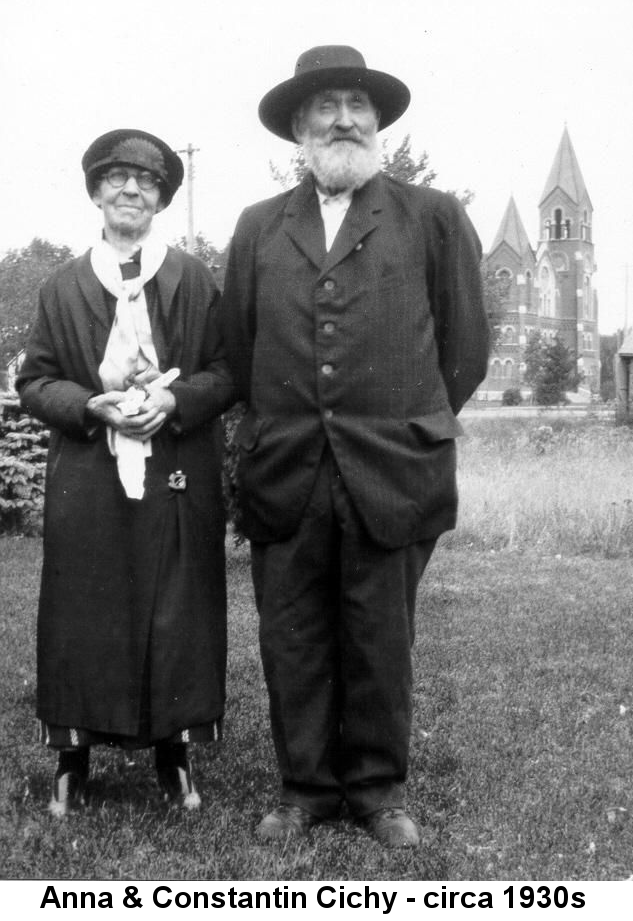

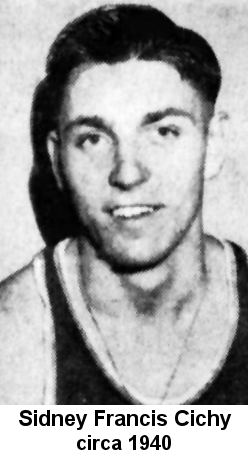

Three Cichy brothers, whose sister was the Wisconsin farmer Francis A. Johnson's wife, Rose: August Cichy was working on his older brother Stephan's farm in Ortonville, MN, about 150 miles west of Minneapolis on the South Dakota line. He did not claim an exemption. His actual registration date was June 1, 1917. Frank Paul Cichy and William Cichy, who lived together on their parents' farm near Millersville, about 25 miles southeast of Fergus Falls, both claimed exemption on the grounds that they were their parents' "sole support".

Alonzo D. Conley, a son of Sarah Dibble and Dr. Ed Conley, claimed exemption due to having a wife and child. Dr. Alva A. Conley, son of Ed's older brother A.T., claimed a physical disability, though we don't know what it was.

Jean Alonzo Curran was a son (yes, son, and that is the correct spelling of his first name) of Dr. Ed's sister Emma Conley and Charles Curran, of Mankato; Jean was a medical student at Harvard when he filled out his card.

Dan Dibble's son Donald Nathan Dibble claimed exemptions because he worked as an undertaker and at the local power utility, both of which he thought were "necessary industries"; he also claimed that his wife was fully dependent on him. Ed Dibble's twins, Willard and Willis Dibble, claimed no exemptions.

George Willard Engstrom, a nephew of Dr. Ed Conley, claimed exemption for his wife and child. His younger brother Glenn M. Engstrom did not.

Alfred Halden, a brother of Ole Morud's wife Eline Halden, who was living in Kalispell, Montana and working as a baggage handler for the Great Northern Railroad, claimed an exemption for his wife and two children. The date on his draft card is May 21, 1917 .

Milton Emmons Holmes, the husband of Dan Dibble's daughter Jean, claimed exemption for his wife and child.

Carl and Helmer Kvern, sons of Lars Halden's brother-in-law Arne, from Fergus Falls, claimed no exemptions.

Some members of a National Guard machine gun company from over in Faribault came to Cannon Falls on a recruitment mission in the last week of June, 1917, and collected several men, but the Beacon mistakenly reported that Archie Dibble was one of them. Archie and his aunt Edith Kowitz Wilson (wife of the barber Ed Wilson) went out to Hysham, Montana, to visit Edith's brother Herman Kowitz in mid-July. They returned about a month later, and Archie went back out there again in mid-September. Herman had greatly expanded his holdings over the previous three years. He owned a meat market in Hysham, and he and his wife Beda (known as "Minnie") now had 640 acres spread across three sections east of Sarpy Creek Road (Rte. 384) and south of where I-94 now runs. The place today is a collection of scrub-covered hills, dry washes and small ponds about three miles southeast of the Hysham Airport.

Among all of the men of our families of an appropriate age during this time, we only know of two who enlisted during the early call for volunteers in the spring of 1917: Charles Clark Ahlers, a son of Alonzo Dibble's first wife Louisa's brother, Alonzo Ahlers, from South Dakota, enlisted on May 2. He served as a Private First Class with the 110th. Infantry Regiment of the 28th. Division, US Army Expeditionary Force. Dr. Frederick A Engstrom, a nephew of Dr. Ed Conley, enlisted on July 21.

Some members of the then-still-small US standing army arrived in Europe in June 2017, and the entire National Guard was activated as part of the army on August 5, but no Americans saw combat before October of that year. Meanwhile, life went on for our families, though the war and its political and ideological imperatives became increasingly intrusive.

A few days after the declaration of war the Minnesota state leglislature passed a bill to create a state Commission on Public Safety, intended to manage and mobilize the state's resources for the war effort. The legislation, passed just before the legislators adjourned for the summer, was not much-debated or scrutinized, and it granted sweeping powers to the Commission to regulate just about everything in the state. Under the law, each county established its own Commission, which carried out the directives of the state body. Ed Dibble's son Willard served on the Goodhue County Commission, representing Stanton Township. Simultaneously the federal government launched the Liberty Loan program, an opportunity for citizens and organizations to purchase interest-bearing bonds to help finance the war. Local officials were also appointed to promote sales of these bonds. The Public Safety Commission got to work immediately. One of its first helpful actions was to issue instructions to the county boards and the railroad companies to ensure that freight cars were used efficiently, and not sent out half-full; counties were told to increase local storage facilities for freight. One of its first examples of overreach was an order that all saloons and cafes that sold liquor must be closed between the hours of 10:00 pm and 8:00 am. More was to follow. A Beacon article on December 14 called the Commission "the official head of our government in Minnesota" and praised its activities in assisting the United States to defeat "Prussian autocracy" and "make the world safe for democracy", including the fact that its seven-member unelected Board had largely replaced nearly 200 members of the state legislature, whose diverse opinions when deliberating on how to address war issues would have been too "unwieldy, expensive and slow." The Commission's efforts so far had been difficult, because, "At the time of the entry of this nation in to the war the people of our state were in anything but a warlike mood. They were prosperous, happy, peace loving and had no idea of the deadly peril that threatened them at the hands of the Prussianized autocratic power seemingly so far removed as to make any thought of danger now or in the future too ridiculous to contemplate." But the Commission and its county coordinators had succeeded in changing people's attitudes, and loyal Minnesotans were now prepared to begin the next urgent task, to "smoke out the Huns within our gates."

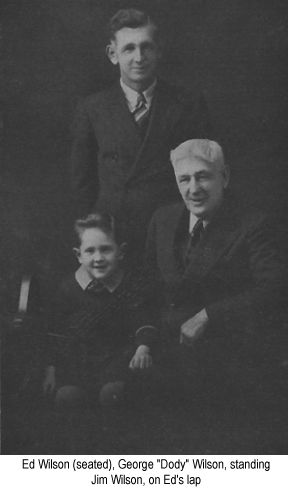

Meanwhile the local Liberty Loan boosters, in cooperation with the Commission, began an increasingly aggressive campaign to convince people to buy bonds. Names of buyers were published in the Beacon, and among the earliest were Dick and Dan Dibble, their cousin Ed Dibble, Dr. Alva A. Conley, and barber Ed Wilson's brother George Elmer Wilson, a Cannon Falls judge and city clerk, as well as loan financier and cemetery monuments retailer. Ultimately sale of these bonds paid for about 58% of the total US cost of the war. An "America First" association was established nationally as well; its statewide and local chapters focused on staging "loyalty" rallies.

Noting that the Minnesota National Guard had been mustered into the regular army, theoretically leaving the state without its protection, the state Commission ordered the establishment of a "Home Guard" in late April to ensure public safety. Home Guard volunteers had to be at least 26 years old and were not paid except when placed on active duty. They added a military flavor to patriotic gatherings and parades, provided honor guards at funerals, escorted newly-enlisted (or drafted) men to the troop trains, and even harvested crops on farms whose young men were serving in the war. Although the Home Guard performed some heroic functions, including assisting survivors of at least one tornado, and of a massive wildfire that swept through northeastern Minnesota in 1918, it also functioned as a military enforcement tool for the Commission's efforts to track down "slackers" (people who failed to enlist in the army or register for the draft), harass people of German descent and those who did not purchase Liberty Bonds, and to quell labor unrest. Spanish-American War veteran Charles J. Ahlers, President of the C. J. Ahlers Electrical Company in Red Wing, nephew of Alonzo Dibble's first wife Louisa Ahlers, and himself a German-American, was the only member of our families known to have joined the Home Guard, though we don't know what Guard activities he participated in. Dan Dibble may also have been a member, though he was only referred to as an appointed member of the "volunteer body organized in Goodhue county, Minnesota, to respond and assist in case the peace of our community should be threatened." Paul Kvern, up in Fergus Falls, may also have been in the Home Guard; he was eventually a member of the Minnesota National Guard unit that it became.

All of these organizations were supported by the federal Committee on Public Information (CPI), whose job was to spread pro-war propaganda to the diverse population of the United States, including many millions of German Americans, some of whom were uneasy about whose side we were on, millions more Irish Americans who did not favor an alliance with Great Britain, and many others who had strong isolationist beliefs. One of the CPI programs was the "Four Minute Men". The name played on the Revolutionary War militias known as "Minute Men", and referred to the time it typically took for a movie theater projectionist to change reels on a feature-length film. The Four Minute Men were trained as public speakers and given topics and outlines, and would stand up and deliver speeches during the reel changes, on topics such as rationing food, supporting the Red Cross's efforts on behalf of soldiers overseas, registering for the draft, and, of course, buying Liberty Bonds. They also spoke at churches, lodges, schools, public parks, auctions, and labor union meetings. Charles P. Hall, and the dentist Samuel Lewis Conley, both served as Four Minute Men. Hall also wrote the lyrics to two songs, "Loyal Red Wing" and "Loyal Minnesota: Star of the North", with music by Ernst Smith, that were sold to benefit the Red Cross in 1917.

Despite all the military and patriotic folderol, and the increasingly sinister repressions of free speech and civil rights happening around them, our folks did manage to do other things.

Ed Dibble helped test phosphate fertilizers on his farm beginning in April. Phosphates had been tested in other parts of Minnesota and not found worth the effort, but they had not been tested in the southeastern part of the state, whose soil was similar to that of other locations where those fertilizers had been effective. The Cannon Falls High School Agricultural Department, working with the University of Minnesota, organized the research. Two six-acre fields on Ed's farm and that of another local farmer were used for the tests, in which different quantities of phosphate were applied and the progress of crops of corn, clover, and "small grains" such as oats or rye, was observed. Unfortunately, we can't find a report on the results of the tests.

On April 6, the Beacon reported that James Andrew Elder, the adoptive father of Navy Lieutenant Charles Milford Elder, had "died very recently at his home in Cordele, Georgia." The paper had reported in February that he was "in very poor health" and he and his wife were planning to return to Cannon Falls. Apparently they didn't do so, and the actual date of his death is unknown. James's widow Elizabeth came to visit her sister near Cannon Falls in late June, and she relocated permanently to Minneapolis shortly thereafter.

Isabel Dibble, Dan's wife, was elected to attend a regional meeting of the state Federation of Women's Clubs in late April. These clubs were a primary means of social and political expression for American women prior to their receipt of voting rights. They operated on the basis that since women were allegedly naturally inclined to take care of the home, they would be good at so-called "municipal housekeeping", which became a synonym for community activism in various public policy arenas. Representatives of these federations gained entry to the offices of male politicians and bureaucrats, who usually listened to them respectfully and sometimes acted on their recommendations. Unfortunately, we have very little information on Isabel's specific beliefs or activities. She was a member of Eastern Star, a mixed-gender offshoot of the male-only Masons, along with Ed Dibble's wife Laura. She also belonged to the "Home Economics Club", along with Bertha Dibble (wife of Dick Dibble), at whose meetings such important topics of home management were discussed as "The Emancipation of the Slaves to Johnson's Administration", "Problems Bequeathed by the Civil War", "Johnson's Administration to Cleveland's Second Administration", and "The Early New England Poets".

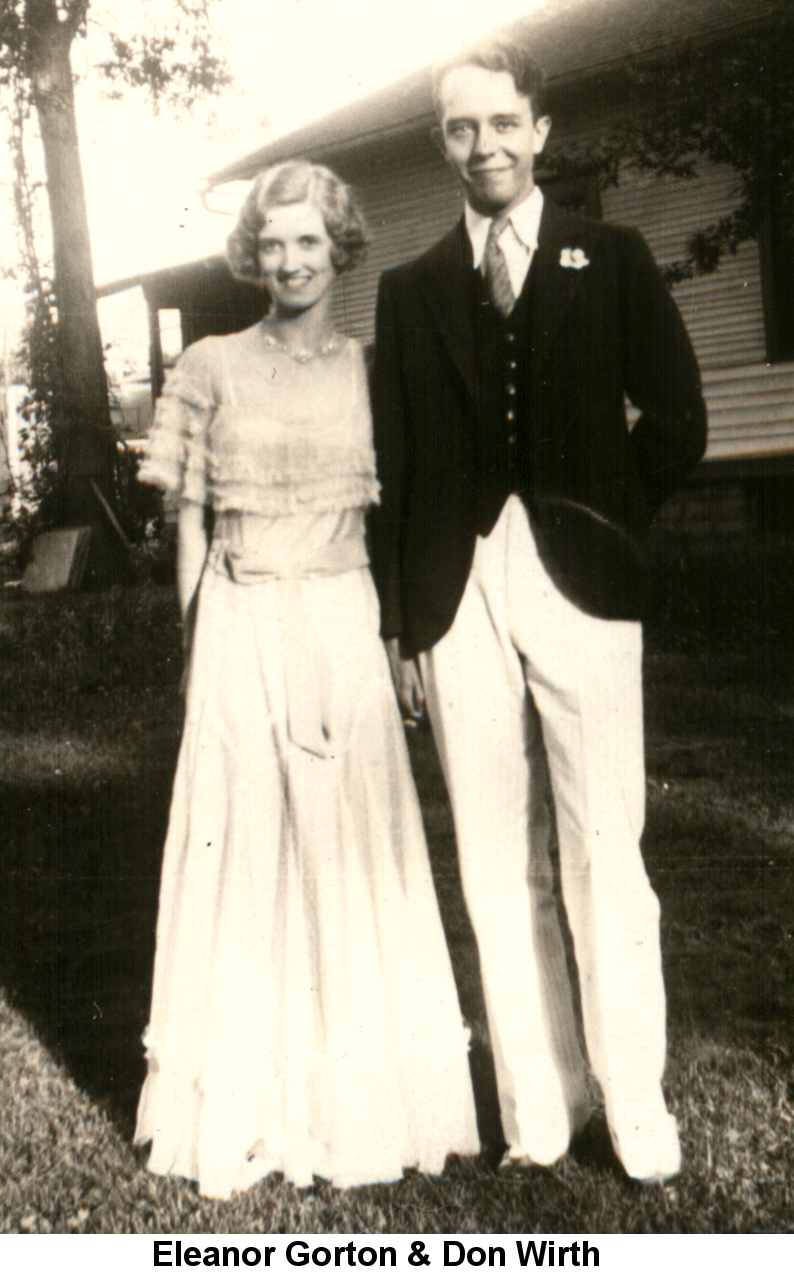

On May 12, 1917, Isabel and Dan's son, Donald Nathan Dibble, the West Concord undertaker, married Margaret C. Brooks in a very small ceremony at his parents' home in Cannon Falls.

That same spring, the Morud farm near Warren, MN was besieged by fire. Prairie fires were always a threat. The farmers would turn over the earth in broad strips around the farmyard each year to try to keep fire away from the house. On this occasion, Ole Morud had left for the grain elevator in the town of Radium, about 5 miles away, with a load of grain. A prairie fire came whipping up from the southeast. Ole's wife Ella tried to start a back-fire to burn out the ground between the house and the prairie fire, hoping to stop it in its tracks. It didn't work, and the barn caught fire. 14-year-old Emma was home from school with a cold, and she managed to get four horses out of the barn. But several calves and chickens, and Ole's prized hunting dog, died.

The Moruds survived this disaster, however, and despite the hardships of life on the cold, windswept prairie, continued to maintain a bastion of culture and education for their nine children. School was so important to the Moruds, in fact, that when the children were in high school--at this time this would have included Alice and Mabel--they rented their own apartment in town near the school to ensure they would be there every day even in rough winter weather. As we shall later see, this determined approach to education produced a high number of educated, professional women among the Morud children, at a time when that was definitely not the norm.

In June, Ora Conley, another educated professional woman who certainly stood out from the norm, and who had been teaching high school home economics in Sauk Center, moved to Minneapolis "to attend summer school at the University" of Minnesota.

On July 7, over in Northfield, another young Dibble was married; this time it was Willard, and his bride was Cora Rose Hanson. Cora was a nurse who graduated from St. Luke's Hospital nursing school in St. Paul. She was "one of the head nurses at the hospital at Phalen Park"; this may have been the State Hospital for Indigent, Crippled and Deformed Children, which was located on land adjacent to Phalen Park in St. Paul (and later known as the Gillette State Hospital for Crippled Children). Cora was born on September 13, 1890, probably in Sioux Falls, Lincoln County, South Dakota. Her parents were Thomas and Mary Hanson.

In August, yet another local booster group, the Cannon Valley Agricultural Association, was incorporated with Ed Dibble as its president.

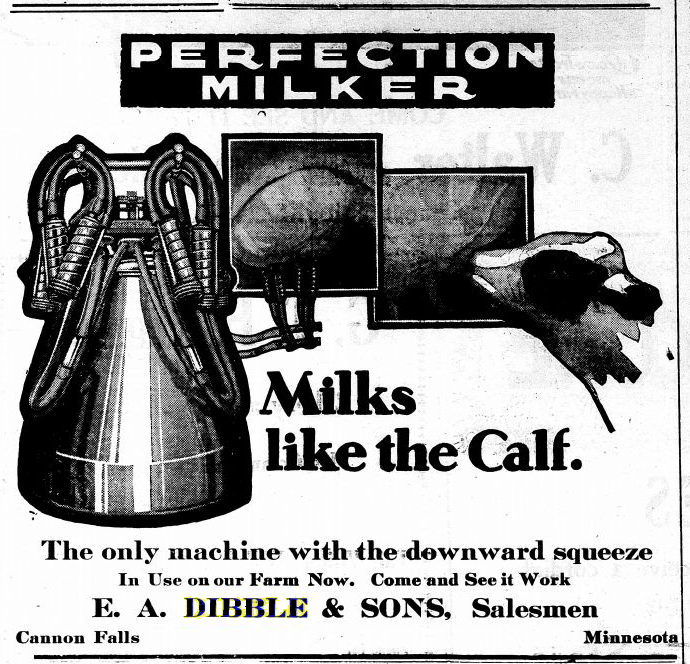

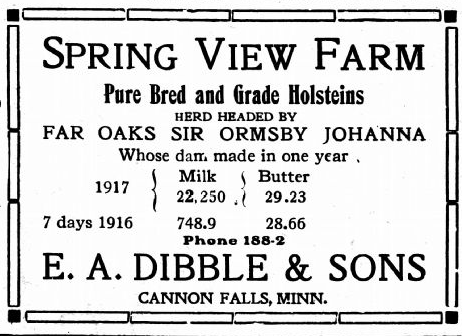

There's a story that Dick Dibble was awarded a contract to supply meat to the US Army during the war. We don't know when, or even really if, that happened. But Dick's farm on Spring Garden Road was certainly producing fine cattle. He won a first prize for Holsteins at the Cannon Falls Fair in late September. Ed, now styled as "E.A. Dibble and Sons", took two first prizes and a second prize for the same breed.

Dick's wife Bertha had broken her arm the previous week while "cranking an automobile"; nevertheless she hosted Dick's daughter Olive and her husband Charles P. Hall as visitors the next day.

Certainly the availability of food for the troops was a big concern, and all Americans were expected to avoid wasting food products. The state of Minnesota, in conjunction with the University of Minnesota and the Federal Department of Agriculture, established an "emergency" Food Conservation program. The program sent out trained "demonstration agents" to teach women new ways to use food substances frugally. Ora Conley took a position as the agent for Pipestone County in early October.

Also in October, Glee Dibble won second prizes in dressmaking in the "combination suit" and "Night Gown" categories; her friend and frequent competitor Frances Thill took the first prizes in both. Glee also played girls' high school basketball that fall and winter.

In November, Laura Dibble, her sons Willis and Willard, and their cousin Alonzo D. Conley were all listed as Liberty Bond buyers. On November 20, 1917, Della Dibble Aslakson's sister-in-law, Pearl Martha Aslakson, married Mark W. Bray in Kenville, New Jersey. At around that same time Dr. Ed Conley and Ed Dibble attended a Loyalty meeting in St. Paul as delegates from Cannon Falls and "towns adjacent". On November 30, Lieutenant Charles Milford Elder was assigned to a post at the US Naval Academy in Annapolis.

On January 17, 1918, Dick Dibble's brother-in-law, George Kowitz, was working as a supervisor in a railroad shop in La Crosse, Wisconsin, and he criticized the work of one of his underlings, Lloyd Knutson. Lloyd "became peevish" and beat him up. He was charged with assault, and he pleaded guilty and paid a fine of $5 plus court costs. Apparently he also lost his job, because he told a newspaper reporter that "he didn't mind the fine as much as he did the enforced idleness."

Later that month, Loring Miner was a doctor in rural, sparsely-populated Haskell County in southwestern Kansas, about 30 miles southwest of Dodge City, and about 30 miles south of Garden City, where Elizabeth Dibble (of the Indiana Dibbles) and her husband William Pate settled around the turn of the 20th. century. As the winter of 1918 progressed, Dr. Miner became concerned about a local epidemic of influenza of a type he had never seen before. Young adults became severely ill very quickly, and many of them developed pneumonia and died. And then, abruptly, the local outbreak ended. But Dr. Miner was so shocked that he published a paper about it in the US Public Health Service's journal, Public Health Reports. Little attention was paid at the time. But in the following weeks some young men from Haskell County reported to Camp Funston at Fort Riley, about ten miles southwest of Manhattan in northeastern Kansas, for military training.

Also in February, Dr. Alva Conley was chosen to be vice president of the Goodhue County Medical Association, and at that time there was no mention of influenza in the Beacon or the Northfield News, except in the usual, endless advertisements for patent medicines.

On another disease front, Dan Dibble's meat market was still going strong in late February 1918, when he was reported to be the primary supplier of meat to the tuberculosis sanatorium.

Meanwhile, efforts to enlist all Americans in some aspect of the war effort had reached even institutionalized disabled people. On February 15, the Beacon reported that "nearly 12,000 inmates" of state institutions in Minnesota were knitting sweaters, scarves, socks, and "helmets", and were also sewing "hospital shirts" and making gauze surgical dressings, for the Red Cross. This included children in the state school for the "feeble-minded" in Fairbault, schools for the blind and the deaf, and the hospital for "crippled children" at Phalen Park in St. Paul, where Cora Hanson Dibble had worked. Sixty allegedly "feeble-minded" knitters were using up $100 worth of yarn a month, or about $1900 in 2021 dollars. The children were also contributing money to the Red Cross, organizing dances "and other entertainments" and charging ten cents admission which they gave to the cause, and even selling Liberty Bonds.

Disabled children weren't the only kids being encouraged to contribute to the war effort. Late in 1917 the federal government came up with "war savings stamps", a less expensive, less remunerative type of bond. A "savings certificate" stamp cost $4.12 on January 2, 1918, and could be redeemed for $5.00 on January 1, 1923. Now, $4.12 in 1918 equates to about $80 in 2021, not an amount every school child could be expected to cough up. But the feds also sold 25-cent stamps, which did not accrue interest, but if a child accumulated sixteen of them over time he could exchange them for a full savings certificate. And if a quarter every so often (worth a bit less than $5.00 in 2021) was still too steep, kids got kits distributed by their schools, with penny and nickel savings booklets so they could save up for a 25-cent stamp. Willis Dibble served on the Stanton Township War Savings Committee, which also included a member of the school board that operated the Dibble School. His brother Willard joined the Colvill War Savings Society, one of many such organizations dedicated to bringing together people who would serve as good examples of "frugality" and who would also buy, and recruit others to buy, war savings stamps. This Society was named for William J. Colvill, who led a Minnesota volunteer infantry regiment in the Civil War.