The famous explorer Zebulon Pike (for whom Pike's Peak is named) visited the mouth of the Cannon, where it meets the Mississippi, in 1805. He was in the neighborhood on assignment from the US government to do the local Dakota Sioux people out of a relatively small parcel of land at the confluence of the Minnesota and Mississippi Rivers and build a fort there. (This was Fort Snelling, located between what are now the Twin Cities of Minneapolis and St. Paul.) Pike valued the 100,000 acre parcel at $200,000, but the Dakota were paid $2,000 for it.

There followed a series of shamefully unfair treaties whereby the Dakota, the Ojibwe, and other tribes gave up successive parcels of land, under pressure, in return for promises of money and goods that were never completely delivered. In the 1840s several such parcels were ceded, mostly by the Ojibwe, along both sides of the Mississippi, and the federal government opened the region for settlement. The region officially became Minnesota Territory in 1849. In 1851, two bands of Dakota people were "persuaded" by threats of an armed military invasion to sell their land to the government, including the Cannon and Little Cannon Rivers and all the land around them. The deal involved both a cash down payment and promises of annual "annuity" payments in cash and goods. Most of the Dakota were sent to live on a reservation along the banks of the Minnesota River, further west. This was not good land, and it was clear that the annuity payments would be essential to keep them alive. A few Dakota did remain in settlements in the eastern part of the territory, struggling to farm and meet the white people's expectations for "civilized" life.

As soon as the territory was organized, a concerted effort began to attract white settlers to it. Local boosters saw themselves in competition with other regions for the wealth that would follow the creation of new communities, industries, farms, and transportation networks. They were eager to promote the territory, and they took every opportunity to have their cheerful views of the prosperous Minnesota future published in newspapers and magazines all across the more populous eastern and midwestern states. Steamboat lines seeking passengers worked together with city founders who needed settlers to promote immigration. Minnesota newspaper publishers filled their pages with articles praising the region, and they encouraged their readers to send copies 'back east".

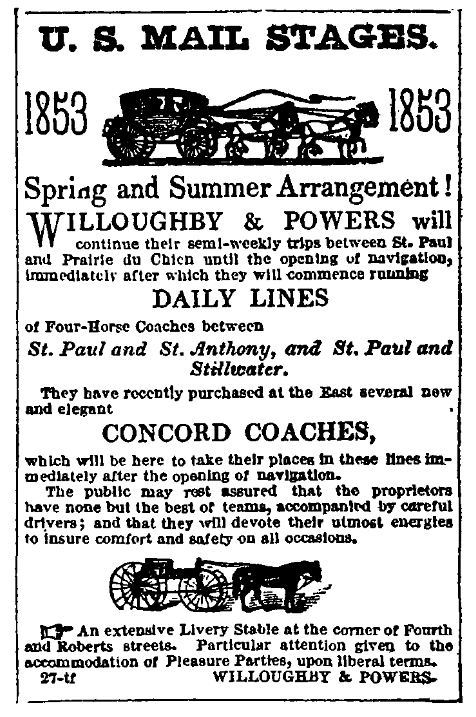

It wasn't long before this clamor for settlement began to focus on the need for roads. Already in 1849 citizens in St. Paul were complaining that the weekly mail deliveries weren't good enough, and that even three days a week wouldn't cut it. They wanted their mail every other day! Farmers staking claims in the back country away from the navigable rivers needed a way to haul in supplies and bring out the harvest.

This demand for roads ran afoul of the growing tensions of north-south sectionalism. Southern politicians believed that the federal government was trying to hem the slave states in by refusing to permit development of roads and railroads in the newly-acquired former Mexican territories in the southwest. Although they repeated old arguments about the impropriety of the government paying for "internal improvements"--a term used by ideaologues in the 1820s version of America's eternal "big vs small government" debate--southerners were simply angry that the federal government didn't want to pay for "internal improvements" for them, so they were bound and determined that it wouldn't provide them for anybody else, including Minnesotans. Proponents of the roads adopted a novel argument that would be re-used a century later by President Eisenhower in his quest to build the Interstate Highway System: the roads were a military necessity. To win this point, Minnesota's Territorial Delegate, Henry H. Sibley, slandered the Dakotas and Ojibways as the "most warlike tribes on the North American continent", and warned that settlers risked rapine and slaughter if the army couldn't quickly come to their aid.

That argument carried the day, and beginning in 1852 Congress passed legislation authorizing the War Department to lay out several roads through the area of southeastern Minnesota. Two of these trails crossed the Cannon River near several small waterfalls where the Little Cannon River met the Cannon. The first was the Mendota-Big Sioux, or "Dodd", road. This route meandered from Mendota (now an inner suburb of Minneapolis), south-southwest to Lakeville, then southeast to the Cannon falls, west-southwest to St. Peter, south to Mankato, and finally southwest to the Big Sioux River. The second road roughly followed the route of modern US 52, from Hastings, through Cannon Falls, Zumbrota, Rochester, Chatfield, and Carimona, and then on to the Iowa line. The latter road connected to St. Paul on the Mississippi River in the north, and eventually to Dubuque, IA, on the Mississippi in the south, and became known as the "Dubuque-St. Paul road".

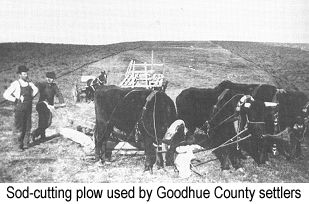

Prairie "road building" at that time didn't involve a lot of earth-moving or ground leveling, but it didn't much matter. As soon as the army surveyors pounded their stakes into the tough sod and settlers could follow them, they started coming in their tens of thousands, on foot, on horseback, and in wagons, and it was their continuous heavy plodding that actually "built" the roads.

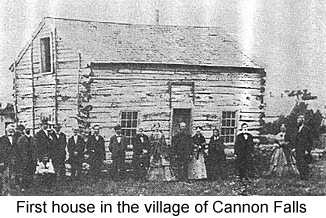

However, the village of Cannon Falls was not founded by those immigrants, but by explorers from the east. Some 30 miles east, to be exact, where the Dakota chief Red Wing had once presided over a village near a wide spot in the Mississippi River called Lake Pepin. The local land agent chose one William Freeborn to check out the area to the west. Freeborn, and a man named James McGinnis, headed up the Cannon and saw the falls. They immediately recognized the water-power potential of the site and its implications for industrial development. McGinnis took one of the first claims in the area, along with Edway Stoughton and a fourth man, the lawyer Charles Parks, who is credited with building the first house in the village in 1853.

Cannon Falls became an important rest stop for people coming up the Dubuque-St. Paul road, in wagon trains up to five miles long. The village historian noted, "On almost any day, the camping grounds were crowded with covered wagons, livestock, and travelers preparing food over open fires." The local boosters added a unique twist to the promotional newspaper articles and pamphlets that they quickly spread back down the trail. Due in part to its cold winters, which were hailed for their ability to kill germs, Cannon Falls was not only considered an up-and-coming industrial center, a "new Lowell (Massachusetts)" in Parks' words, but was thought to be a haven for people with "consumption" (tuberculosis) and other illnesses that thrived in warmer climates. These qualities fostered a firestorm of land claims, claim-jumping and speculation in the area as hundreds of people arrived almost daily between 1854 and 1857.

Several Indiana residents were among the earliest settlers. In the summer of 1854, two of them were the Dibble brothers Alonzo and Jonathan. They settled on adjacant claims about two miles southwest of Cannon Falls and became Stanton Township's second and third settlers. (Stanton was the original name chosen by the settlers, but some territorial or state bureaucrat found the name "unacceptable" for reasons that have not been recorded, so they changed it to "Lillian". Some time later, perhaps after the bureacrat retired, they changed it back to "Stanton".) Alonzo's original claim, totalling a quarter-section of land, or 160 acres, contained a spring, later known as Dibble Springs, which was one of the reasons Alonzo chose the place. He built a one-room log cabin near the water source and he probably rented or borrowed a special sod-cutting plow, drawn by oxen, to break up the tough prairie sod and plant his first crops.

Alonzo's first germ-killing winter in Minnesota may have been healthful. It certainly was harrowing. A young couple, George Season and his wife, had come with the Dibbles to the new land. Mrs. Season had trouble during childbirth, and Alonzo left at 4 am to walk nearly 30 miles to Red Wing, no doubt in cold and snow along the most primitive of roads, to get a doctor. Of course, time was of the essence, so the doctor took off immediately for the Season farm on horseback, leaving Alonzo to catch his breath and then turn around and walk all the way back home. Sadly, on his return he learned that Mrs. Season and her child had both perished.

The land rush continued and intensified. The first white settlers had been largely of English extraction, but almost immediately, groups of Germans, Norwegians and Swedes arrived. Each group stuck to themselves for the most part, with the "English" people settling around Cannon Falls and Red Wing, the Scandinavians occupying the central and southwestern areas of the county, and the Germans settling south of Red Wing in the Hay Creek area. Among the Germans arriving in 1854 were Charles Ahlers and his 18-year-old daughter, Louisa Wilhelmina, who was born on February 24, 1836 in Prussia.

Back in Prussia Mr. Ahlers was known as Karl. He was born there in around 1803. His wife was also named Louisa; she was born around 1813. In addition to the younger Louisa, the couple had a son, Karl (also later known as Charles), born August 23, 1835, a daughter Maria born around 1838, and a son Julius, born around 1848. The Ahlers family first arrived in New York City on the ship Elise on June 28, 1853. Karl (Charles) Sr. staked a claim in Hay Creek in 1854. The following year he, his wife Louisa, and his son Charles Jr. were founding members of the German Methodist Episcopal Church in that little town.

By early 1856, Charles Ahlers had nearly completed his first log cabin on his claim near the Zumbrota Road in Hay Creek, not far from his church and Burkhard's hotel. (Today, as best we can tell, this is near the corner of Route 58 and 315th. Street, just a couple miles south of the Red Wing High School.) But sadly, as seems to be the case in any land rush, claim jumping was a common activity among the new settlers in the area.

The problem was made worse due to mismanagement related to the "half-breed tract". Because mixed marriages between white and Native American people had become common in the plains regions, and the children of those marriage were frequently victims of discrimination by both groups, some well-intentioned people proposed that land be set aside for them where they could establish local government and civil rights for themselves. These regions were called "half-breed tracts", and there was one running along the south shore of Lake Pepin that was established by the 1830 Treaty of Prairie du Chien. Its northwest corner included the area that became Hay Creek. As might have been expected, a lot of mixed-race people did not actually want to live in these segregated areas, and the land was largely empty until the Minnesota land rush began in the early 1850s. That's when the trouble started.

There were some mixed-race people who had occupied some of the tract. They soon were surrounded by white people, who began settling on the land before the1851 treaties were ratified by Congress. Some of these settlers may have been ignorant of the land set-aside, and saw the mixed-race people as "just" Indians, who were supposed to be gone. Reports that the tract contained valuable minerals, including lead and copper, increased the demand for lots there.

In 1854, the federal government seized the tract (according to one source, citing alleged treaty violations), and opened it up for general settlement. The government offered 640 acres of unsurveyed federal land, presumably elsewhere, to the mixed-race inhabitants who agreed to leave, and those who took the deal were promised "scrip" that could be exchanged for that land. The actual scrip didn't arrive until 1857, but meanwhile a lot of deals went forward without appropriate documentation, including illegal sale of future scrip to land speculators, who re-sold it to settlers who wanted land inside the tract. This led some people to believe they owned land that other people were already occupying.

Things started to get ugly, and Charles Ahlers Sr. was in the thick of it. As he was finishing up the cabin in early 1856, a mob of men showed up with clubs and axes. The mob's leader claimed that Charles was on his land; that he had carved his name on a nearby tree before Charles ever set foot there. We don't know if Charles or the interloper based their claims on an illegal scrip deal, but the man demanded that Charles either abandon the claim or pay for it. Charles had little choice; he paid up. He finished the cabin and his family lived there peaceably. Charles was known as a friendly and helpful citizen who frequently offered the hospitality of his cabin to travelers.

Over on the quieter west side of the county, Stanton Township's namesake, William Stanton, arrived from Vermont during a memorable week in 1855 when his group of settlers claimed a total of 3,000 acres in three days.

Also among the year's new arrivals was John A. Wilson, a 30-year-old lawyer from upstate New York. John was born on March 1, 1824 in Howard, about ten miles from Canisteo in Steuben County, in New York's Southern Tier. His father may have been Hawley Wilson, and John may have had a younger brother, though we don't know his name.

A letter written by a settler that summer notes, "This renowned place we found to consist of two log hotels and two cabins for private residence. The town is regularly laid out and the rush here is great. Every day numbers are coming in and making claims anywhere in the vicinity and it doubtless soon will be quite a town. There are two or three good waterfalls here, sufficient for a large amount of machinery!"

The 28-year-old Alonzo must have been feeling at least as optimisic as the letter-writer. Although he'd barely had time to build a cabin, and could not yet have brought in a crop, on June 11, 1855, Alonzo married Louisa Ahlers. Louisa also got a new brother that year, Alonzo, born September 22, whose name may have been inspired by the other recent addition to her family. That fall the elder Alonzo participated in the first political election in Cannon Falls, as one of the thirteen registered voters.

1855 also saw the birth of Hiram Edward Conley, a future major player on the Cannon Falls scene, in Iowa.

The Conley family came from the St. Lawrence River valley of upstate New York. Hiram's grandparents were Thomas Conley and his wife Sylvia, and their first child, Lewis Conley, was born in Leroy, Jefferson County, NY on November 20, 1822. Soon after that, the family moved to the Town of Alexandria in Jefferson County. This township is the site of the prominent tourist destination of Alexandria Bay, on the St. Lawrence, but the Conley farm was a couple miles away from the river, on the shore of Butterfield Lake.

Lewis was one of the local public school directors and was given the job of finding a new teacher for the school. The minister of his church in neighboring Macomb, St. Lawrence County, recommended a young lady, just turned eighteen, for the job. She was Betsey Hutchins, born June 16, 1827 to Bradley and Syrena Hutchins. He gave her a three month contract, which turned into a courtship, and they were married on March 25, 1847 in Macomb.

Lewis Conley was an ambitious, or perhaps just curious, man. The couple initially lived in Rossie, St. Lawrence County, where he burned lime, an ingredient for mortar, for a living, but soon moved to an 80-acre farm in Alexandria, where he ran a sawmill. Their first child, Alonzo T. Conley, was born there in 1848, and a second son, Melvin D Conley, was born there on February 26, 1850. Lewis got tired of running the mill and struck out for the west in May, taking a steamboat with his brother Wesley up the river and through the Great Lakes, and spending several months in Batavia, IL, before returning home.

In October 1851 the Conleys left New York for good, eventually arriving in Linn County, Iowa in 1853. They rented a log shanty near Palo, just a few miles northwest of Cedar Rapids, and there, five weeks after their arrival, their third son, John Wesley Conley, was born. Hiram Eldredge Conley, their fourth boy, was born there on July 11, 1855.

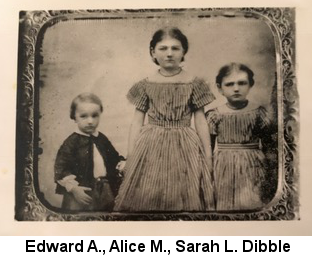

Back in Stanton Township, Goodhue County, MN, Alonzo's and Louisa's first child, Sarah Louise Dibble, was born the following spring, on May 27, 1856. When Louisa came due, Alonzo remembered his experience with Mrs. Season, and he drove his wife in an oxcart to stay with her mother in Hay Creek, where she would be nearer the doctor.

Five new school districts were created in Goodhue County in 1856, and many new roads were also built, to accommodate the settlers. In that year's elections, Alonzo not only presumably voted as part of a much larger electorate, but also served as one of three "judges of elections" for the Cannon Falls precinct.

Rapid settlement continued into 1857, when the Chapman family, including Rebecca Chapman, arrived from New Hampshire.

The Chapmans probably consisted of several households who settled in Lillian/Stanton Township and the village of Cannon Falls. Benjamin Chapman, the patriarch, was a deacon who helped found the Cannon Falls Congregationalist Church. He was born on September 20, 1796, and before he brought his family west, he had a farm on Bramble Hill in North Hampton, Rockingham County, NH. While there, he and his first wife, Hannah, whom he married on September 15, 1818, had several children, most of whom died as infants or toddlers. Those who survived were Leonard Willey Chapman, born April 6, 1823, Joseph Edward ("J.E.") Chapman, born December 12, 1825, Rebecca Sarah Chapman, born June 23, 1830, and Simon Leavitt Chapman, born April 22, 1836.

By 1857, Hannah Chapman had died and Benjamin had remarried to Louisa C. Brown, who was born on April 20, 1814. It was this couple who arrived with Rebecca (and probably their other children) in burgeoning Goodhue County and its seat Cannon Falls, which had reached the size of 1200 residents.

Meanwhile, south of Red Wing in Hay Creek, the land situation got worse before it got better.When the actual scrip showed up, people began trying to formalize their claims at the land office in Red Wing. The scrip holders argued, reasonably enough, that any white settler who occupied land in the "half-breed tract" before the treaty was ratified had no right to be there. But those settlers disagreed--violently. In the absence of official police and judicial authority, they seized the land office and set up an armed guard there, and they established a local committee to "try" land disputes. These "trials" often consisted of armed intimidation of scrip-holders, who were "persuaded" to turn in their scrip. This usually worked, but not always without a fight, and it seemed as though the constant pressure of rapid growth might bring on more violence.

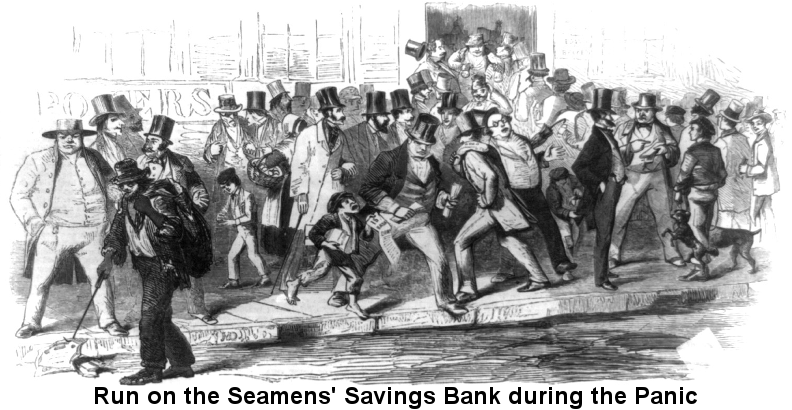

And then, everything crashed to the ground. On August 24, 1857, the Ohio Life Insurance and Trust Company of New York ran out of money and stopped making payments on its debts. This triggered a string of bank failures across the country as each bank's creditors were unable to collect their payments, and almost overnight, the supply of ready cash dried up. This was the Panic of 1857, and Minnesota, with its hordes of bank-financed land speculators, was in the thick of it. Property values dropped all along the Cannon River, and nobody was in a position to lend money to farmers to buy seed or to real estate developers in town. The vast hordes of settlers left as quickly as they had come. By the summer of 1858, Cannon Falls had shrunk to a hamlet of 300 people and those remaining dissolved the village corporation.

Among those who returned from whence they came was Alonzo's brother Jonathan, after September 27, 1857, though we don't know for sure that the Panic was his reason. The year was made bleaker still when the Dakota people were forced to cede the northern bank of the Minnesota River--half their reservation--to the United States.

However, not everyone on the roads around Cannon Falls was leaving in 1858. In May of that year, the federal government finally stepped back into the "scrip" fray, and produced a settlement in which the illegal squatters in the tract were allowed to keep the land, and the future still seemed bright enough that Minnesota was granted statehood.

Also in that year, a child named Peter S. Aslakson and his parents, Sven and Liv, arrived from Norway. Sven Aslakson Odegaard was born in Vinge, Telemark, Norway on September 9, 1818. Odegaard was the name of the farm where he was born (Gaard means "farm" in at least one Norwegian dialect. We don't know what ode refers to.) Most Norwegians only had one name in those days; when necessary to tell one from another, their father's name was added, and if still further differentiation was needed, then the place where they were living was appended--but not as a name, as an "address". More information on Norwegian naming conventions is here. Vinge is about 90 miles west of Oslo. Sven married Liv (also known as "Lizzie" and sometimes as "Elizabeth") Petersdotter Voltvedta in Rauland, Telemark, Norway, perhaps in 1852. She was born on March 28, 1827. Their son Peter was born on June 3, 1852 (which poses a delicate problem--at least for those living in Victorian times, as this family did). The family settled into Mineola Township on 160 acres purchased, the story goes, "from an Indian squaw". This farm was probably near the corner of County 50 Blvd, 400th. St. and 135th Ave. in Mineola, just south of the Mineola Lutheran Church.

Not long after the Aslaksons' arrival, on Halloween, Alonzo Dibble's second child, Alice M. Dibble, was born.

By 1859, the financial situation eased. Gold and silver coins began to return to circulation and Minnesota experienced an exceptional wheat harvest, enough to export for the first time, at 50 cents a bushel. Alonzo built a better house on higher ground, away from the spring.

Meanwhile, whether due to discouragement with the economy or perhaps to find a wife among his childhood sweethearts, Jonathan was back in Indiana. On November 2, 1859, he married Ann Eliza Smith at her parents' home in Gallatin County, Kentucky. She was probably born on January 21, 1838 to Daniel and Olive Smith. Ann grew up in and around Rising Sun in Ohio County, but by 1852 her family had moved to Gallatin County, about ten miles further south on the other side of the Ohio River. By the time of their marriage the Smiths had three sons and seven daughters, including Ann, and Sarah C., who was probably born in 1848. The river posed no barrier to trade or socializing, and Jonathan may have known both of them as children before he went to Minnesota, or he may have met Ann and her family in the environs of Patriot in Posey Township, or in Rising Sun after his return. By June of 1860 the 22-year-old Jonathan and his equally young wife Ann were living in a rented house in or near Patriot, not far from his parents' homestead. Living with them was Jonathan's 20-year-old brother Sylvanus.

The separated brothers' families continued to grow. On the farm in Stanton Township, Alonzo's and Louisa's only son, Edward Alonzo Dibble, was born on June 21, 1860. In 1861, as war between North and South began, Jonathan's and Ann's first child, Nathan North Dibble, was born. That's a rather distinctive name. Just a couple of years earlier, a storekeeper in North's Landing--just across Grant's Creek from Posey Township--named Nathan H. North had married one of the Searcy sisters, America. Two other Searcy girls had married Jonathan's brothers, Charles and Henry, so Jonathan likely would have attended this wedding. He probably shopped in Nathan's store. The two men were around the same age and may even have been friends.

At some point before November 1, 1862, Jonathan's family moved a few miles north to Rising Sun, Indiana, because that is when and where Ann gave birth to their second son, Richard Dibble. (Richard's name is sometimes given with a middle initial of "F", though I have found no official sources for this.)

Back in Stanton Township, 1861 saw the birth of the "Dibble School". An enthusiastic young man, Wilbur H. Scofield, had been hired as the schoolteacher for the district, but the job involved more than writing on chalkboards and wielding a hickory switch. He had to find a school. Fortunately, Alonzo Dibble had a vacant building to offer. This may have been Alonzo's first cabin down by Dibble Springs. More likely, it was Jonathan's abandoned shack. The school appears on an 1877 map just inside the northern boundary of what had been Jonathan's first claim (now absorbed into Alonzo's farm), a mile and a half away from Alonzo's new house. (This is probably about where a house and garage stand today at the corner of Oxford Mill Road and Stanton Trail, about a third of a mile east of the Summit Golf Club.) At any rate, as fall turned into winter, Scofield made the rounds of the neighbors with an ox-drawn sled, hustling up wheat to trade for wood to build a floor in the "new" schoolhouse. He contributed $1.60 of his own money, and collected cash from the farmers to buy a heating stove for the school. On December 9, the school opened with seven students in attendance. The morning of December 23 must have been especially cold and snowy, as all the students were tardy except for Alonzo's 5-year-old daughter Sarah, and she may only have been on time because Scofield was living with Alonzo's family and brought her to school himself. This was a circumstance he was not very happy about, as Alonzo apparently made his children sleep in the attic so Scofield could have his own room. The following spring saw him in a better mood, though; Alonzo was making maple syrup and Scofield was hoping to get some.

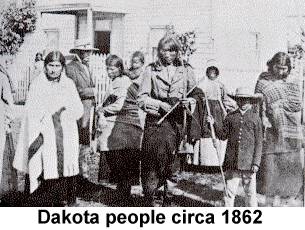

As the Civil War heated up in the south, another war caught fire up north. Left with only the very worst of the bad lands in western Minnesota, the situation of the Dakotas had became very tenuous by the summer of 1862. That year, their annuity payments were delayed, and rumours began making the rounds that gold was in short supply due to the Civil War and the Great Father in Washington would not be able to pay at all. Annuities had always been paid through the operators of the trading posts, who typically kept most or even all of them as repayment for alleged debts owed by the Dakotas. These "debts" were often inflated or even fraudulent. The Dakotas were planning to demand direct payment of the annuities and the traders got wind of it. They declared they would no longer sell food or supplies on credit, and the Dakotas began to starve.

This is the context in which the events that followed, known as the Dakota Conflict, occurred. There seem to have been several separate outbreaks of violence, some of which were unrelated except by the rage and desperation of starving people who had experienced ten years of double-dealing. The killing spread across an area of some 40,000 square miles in central Minnesota, including three major battles, in August and September of 1862. The story of one such incident goes like this:

On August 17, 1862, four Dakotas were standing by a white farmer's fence near Litchfield, about 40 miles west of Minneapolis, hungrily eyeing a nest full of hen's eggs. One man proposed taking the eggs, but another urged him not to, insisting that it was wrong to steal. The men began to argue about who was afraid of the white men, and to prove he was not a coward, one of them raised his gun and began shooting the people on the farm. Five men, women, and children were killed.

The men returned to their settlement and reported what they had done. There was much argument about the propriety of the act, but the local leaders reasoned that, right or wrong, it would surely bring down the wrath of the entire US army upon the Dakota, and the only reasonable response would be to drive the settlers out of Minnesota before that happened. The Dakota were going to die anyway, they said, and it was better to die in battle than of starvation. So a war party was assembled and sent out to massacre the whites.

The settlers around Cannon Falls were never closer than 60 or 70 miles from this bloody business, but there were still communities of impoverished Dakotas at Red Wing and Eden Prairie, and there was no reason to assume that they would not join the killing frenzy. Alonzo fed those who sought his help, and though his daughter Sarah was "deadly afraid" of them, she remained observant. "Each Indian stuck his piece [of bread] in his blanket and withdrew his hand quickly," she later wrote. "I looked, expecting the bread to fall out at their feet and have always wondered why it did not." Sarah also recorded that, "a man rode by our house every day to tell us how far the Indians had advanced but they never came near to where we made our home."

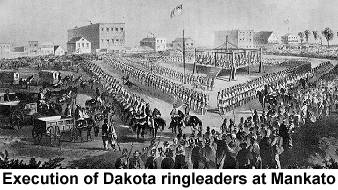

About 500 settlers were killed by the time the Minnesota militia, augmented by a regiment of Civil War veterans hastily sent north, put down the warring Dakotas. 393 of them were rounded up en masse and tried; 303 were sentenced to be hanged amid strident cries for blood and several attempts at vigilante justice by mobs of settlers. President Lincoln, upon receiving this report, was concerned by the large number of death sentences and asked to review the trial transcripts. Minnesota Governor Ramsey demanded that all of the condemned be put to death, lest the state explode in an orgy of mob violence. But an Episcopalian Bishop, Henry Whipple, wrote Lincoln to set the record straight on the duplicitous behavior of the settlers, traders, and local military that had led up to the violence. Lincoln commuted 265 of the death sentences. 38 Dakotas who had been identified as ringleaders were hanged in a mass execution at Mankato, about 40 miles west of Cannon Falls, on December 26, 1862.

Determined that such a thing should never happen again, but unwilling to ensure it by restricting the behavior of white settlers and traders, Congress, in April 1863, cancelled all further annuity payments to the Dakotas and moved all of the reservation dwellers out of Minnesota, settling them in South Dakota and Nebraska.

Some of the Indiana Dibbles saw war and death from a much closer vantage point. Three of Silas's sons served the Union cause. Sylvanus left the comfort of his brother Jonathan's home to go to war as well. He did not return. On December 3, 1863, Sylvanus Dibble died in an army hospital in Nashville, Tennessee, of dysentery. (For much more on this, see Indiana Dibbles in the Civil War.)

We know nothing of Jonathan's business or state of mind at this time. It's conceivable that he had grown close to his younger brother over the last few years, and was so upset by his death that he felt compelled to leave the scenes of their association behind. Or it may simply be the legendary Dibble wanderlust that drove him forward. Whatever the reason, Jonathan was clearly unsettled around this time. He suddenly pulled up stakes and returned to Minnesota, with his wife Ann and his sons Nathan and Richard, probably in 1864.

We don't know in what part of the year he returned, but his family first stayed with Alonzo's brood in Lillian/Stanton Township. A Minnesota State census enumerator caught up with them there in June 1865. He listed them as a separate family, right after Alonzo's. By that time Jonathan's (probable) original cabin was housing the Dibble School, but Alonzo may still have had his first house near the spring, and perhaps Jonathan's wife Ann and the toddlers Nathan and Richard stayed there. Jonathan himself was serving in the army at the time, as noted by the enumerator.

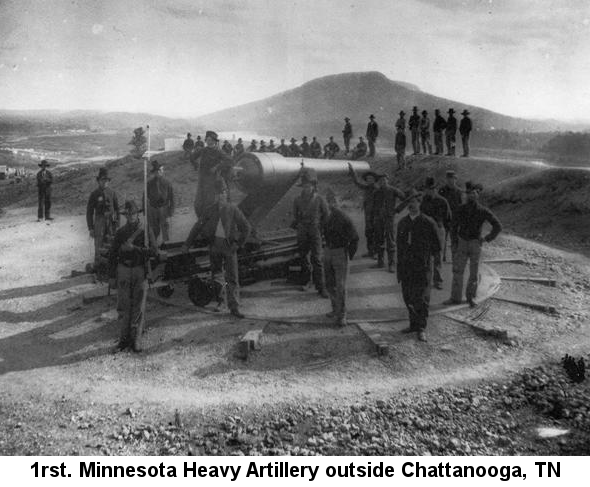

He joined up on February 7, 1865, in Cannon Falls, and was inducted on February 11. He was assigned to Company H of the First Minnesota Heavy Artillery Regiment in April, perhaps even after General Lee's April 9 surrender to General Grant. The unit was sent to guard the fortifications of Chattanooga, Tennessee in case General John Bell Hood (famous for losing Atlanta to General Sherman) tried to retake the city. However Hood, by then, was in Mississippi and planning to surrender. Jonathan's regiment saw no combat, and it was disbanded on September 27. During his service, he probably met the unit's 14-year-old drummer boy, Albert Woolson. Woolson became the last Civil War veteran to die, in 1956, at the age of 106.

His decision to enlist that winter, so soon after moving his young family over 800 miles from southeastern Indiana to southern Minnesota, when the war was all but over and its outcome quite obvious to both sides, seems strange. Even if he had been mulling it over since Sylvanus's death, the obvious lack of military urgency at this late date suggests a continuing unsettled emotional state.

Jonathan was formally discharged from the army in September, but he was probably back home in Minnesota well before then. He received his last pay on April 30. The army sent him home with $6.44 to buy civilian clothing. He bought his musket (with "accouterments") from the army for $6.00, and the army sold him a horse with tack for another $66.66.

Some time after he rode his army horse back into his brother Alonzo's dooryard, Jonathan took up farming in Warsaw Township, where he had claimed 40 acres in the northeast quarter of the northeast quarter of section 12. Today this appears to be near the right-angle curve of 63rd Avenue Way, a mile or so northeast of the Cannon River Driving School.

By then he seems to have been firmly committed to life in Minnesota--or perhaps his wife was trying to make a point. One of them named their new daughter, born March 10, 1867, Minnesota. She was called "Minnie" for short, which was no doubt quite a relief to her in the schoolyard.

William H. Kelley, the Mormon (Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints) missionary, arrived in Minnesota in 1868, where he seems to have had a striking, though short-lived, effect. He apparently induced Jonathan and Ann to briefly join the Mormon church. She was baptized by Kelley on June 22, 1869, and on November 7, local veterinarian Charles F. Burrows became the presiding elder of the newly organized Little Cannon Valley branch of the Reformed Latter Day Saints. Kenyon Postmaster Samuel Clapp was chosen as priest, D. C. Stranahan was appointed clerk, and Jonathan was named "Teacher", an office similar to that of a deacon. The congregation had 17 other members. This organization didn't last long. On December 28, 1874, Kelley wrote that he "spoke to a full house, at the old place of meeting in the Little Cannon Valley. The brethren, so far as yet seen, remain firm in the faith, and appreciate and delight in the beautiful system prepared to make them free. They have heard no sermon for over two years, and have been scattered, insomuch that no meetings of any kind have been kept up." By 1875 Burrows was gone, having moved some 80 miles southwest to Lake Crystal, near Mankato, MN. None of Jonathan's children seem to have been practicing Mormons. It was, no doubt, a brief flirtation, inspired, perhaps, in a revival tent on a hot summer night by the simmering oratory of a charismatic preacher, but in the end only a small disturbance on the surface of the placid pool of the Minnesota Dibbles' Episcopalianism.

It was probably sometime during the war that the Coplin family first arrived in Cannon Falls. Norman Coplin was born in around 1839 in Lenawee County, Michigan, about 50 miles southwest of Detroit. His father, Jared Coplin, was born on October 9, 1796, probably in or near Cayuga County, New York. His mother was Parinthia Blake, known as "Parney"; she was born in around 1806. She and Jared may have been married the day before Christmas in 1825 in Cayuga County. Norman was the fourth of their seven sons. He was on his own and working as a miller by the age of 21. Wandering seems to have been a traditional lifestyle of millers; the German song "Das Wandern ist des Mullers Lust" put it this way:

"Traveling by foot is the joy of the miller.

He must be a bad miller, who never got the idea

of walking from place to place."

Norman certainly did wander. He was probably in Three Rivers, MI (about 30 miles northeast of South Bend, IN) when he married Eliza Payne; their first child, Hattie B. Coplin, was probably born there in 1861. Their second child, Albert Coplin, was born on April 15, 1863. We don't know where he was born, but he died only a little more than a year later, on September 11, 1864, and he was buried in the Cannon Falls Community Cemetery.

After his death Norman, Eliza and Hattie returned to the bosom of their family in Three Rivers, where their third child, Ella G. Coplin, was born on December 10, 1864. Sometime after that, they returned to Cannon Falls. Their fourth child, Cora Coplin, was born there on June 18, 1870 and died just three months later, on September 25.

In town, John Wilson was becoming a successful and popular lawyer, winning respect among the citizens of Cannon Falls. He married Susan Margaret Poe on October 10, 1865. Susan was born on March 7, 1844 in Center Township, Hendricks County, Indiana. Her parents were Margaret Kemmer and Richard Morris Poe. John and Susan's first chld, Edward Richard Wilson, was born on November 29, 1867. Also born that year was Cannon Falls' first baseball team, on whose successor team Edward would later play.

Birth and death are a familiar cycle in all times and places, but in those days of primitive medical technology and vast distances that doctors traveled no faster than a horse could trot, the wheel of life spun faster. On March 25, 1869, Alonzo's 33-year-old wife Louisa died. Just a few weeks later, on May 3, about the time when a young Norwegian couple, the Haldens, was arriving at their new homestead in Fergus Falls, MN, Jonathan's and Ann's third son, Daniel Smith Dibble, was born. And then on August 17, John and Susan Wilson's second child, George Elmer Wilson, was born. (The Wilsons had three other children who died very young, as well as a daughter Kate, who was born on April 17, 1875.) The following winter, Ann may have prematurely given birth to a second daughter, Ann E Dibble, on January 17, 1870, who died just nine days later, on January 26.

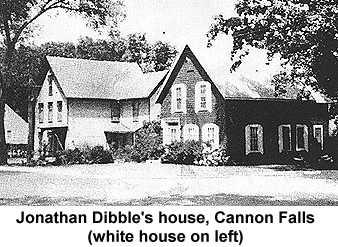

By 1870, Jonathan's Warsaw Township farm, near the hamlet of Sogn, had expanded to as much as 200 acres, including 100 acres of woodland. The farm was valued at $3000.00, and Jonathan had two horses, five milk cows, five beef cows or oxen, 20 sheep and 40 pigs. He produced 600 bushels of oats, 500 bushels of spring wheat, and 200 bushels of rye. By 1875, like many well-to-do farmers of the age, he had moved into town. He bought one of the village of Cannon Falls' first three private homes, a 2-story frame house at 311 N. 6th. Street (now 319 6th. St. N), from Al Leach, who had bought it from its builder, the sea captain Charles Gellett. He also opened a livery stable, a place where one could rent horses, carriages and wagons, and harness.

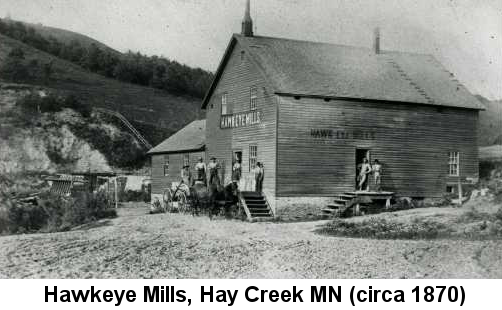

It was probably a prosperous business, owing to growth from the continuing stream of immigrants. Still, the town had not yet fully recovered from the 1857 panic. In 1870, Cannon Falls had a population of 700 people, "mostly American and Swedes", according to a promotional tract produced by Minnesota businessmen in that year. The village also had "2 large flouring and 1 woolen mill, 3 churches, 3 stores, shops, etc., but no hotel." Compare this to the two hotels that were there in 1855, and the population high of 1,200 people in early 1857. Wheat was "king", though, and there were 17 (mostly flour) mill sites within two miles of the village center, drawing power from the many little waterfalls on the Cannon River. John Wilson was serving as the village's Justice of the Peace.

Things were also looking up for Jonathan's widowed brother. On August 28, 1870, Alonzo married 40-year-old Rebecca Chapman, daughter of the devout Congregationalist deacon, and Stanton farmer, Benjamin Chapman. They were married in the Episcopal Church of the Redeemer in Cannon Falls. Rebecca's brother Joseph Edward ("J. E.") Chapman had served on the church's building committee four years earlier (though he had been a founding member of his father's Congregationalist church six years before that), and he was one of the witnesses who signed Alonzo and Rebecca's marriage certificate. While it wasn't terribly unusual for a woman to leave her family's denomination to take on that of her husband in those days, it was perhaps rather more "scandalous" for a deacon's daughter to do so, and even more strking that her brother also left his father's church.

Rebecca, though, seems to have led a fairly independent life in other respects. In 1860 she was living not with her father but with J. E., a tinner (sheet-metal worker) in Cannon Falls, along with a 9-month-old baby named Eva Chapman and two other women. One of these was an 18-year-old Norwegian domestic servant named Clara Peterson; the other was 58-year-old Jane W. Paxton. We don't know who Jane was, but it seems likely that J. E. was married and either the enumerator missed counting his wife or she died in childbirth, and Jane was J. E.'s mother-in-law. In July 1870, just before her marriage to Alonzo, Rebecca was working as a seamstress and living with a 23-year-old Swedish store clerk named Alson Andrus in Cannon Falls.

After the wedding Rebecca lived with Alonzo on his farm and took on the care of his children Sarah, Alice and Edward. Sarah later recalled that she was a good stepmother who encouraged their education. Much later, Alonzo's granddaughter Della would tell the story that her father Ed once asked Alonzo why he had married again. Alonzo said, "to take care of you," and Ed replied, "Well, look at the holes in my pants!" But there was another Sarah present on the Dibble farm at this time. Alonzo's mother, Sarah Howe Dibble, still sprightly at 71, was there in August of 1870 when the census-taker came. She may have come north from Indiana to help Alonzo out with the kids before he and Rebecca married. She did not stay indefinitely though; she returned to Patriot, Switzerland County, IN, where she died on January 16, 1875.

Not much more than a year after their marriage, on October 17, 1871, Rebecca's father Benjamin died. An obituary published the following April reported:

"During his closing months, he passed through severe bodily suffering, having for twenty-five years had a cough which ended in consumption. His last years here also clouded by the severest domestic affliction; through all of which he passed with resignation and the most implicit trust. The closing weeks were but a patient waiting for the Master's coming.

When at last too feeble to kneel in prayer, he leaned over, supporting himself with his cane, saying, 'Like Jacob, I worship leaning upon the top of my staff.' As he was assisted the last time from his chair to the bed, he said, 'Henceforth, the Lord must be my only support. All my comfort is in the hope of the blessed future rest.'

This Christian faith, which had witnessed for God in the church more than fifty years, gained an absolute conquest over 'the last enemy.' This Christian life has left with us a savor that will not soon pass away--the aroma of spikenard, precious to its possessor, more precious in its diffusion."

Rebecca no doubt had her hands full with Alonzo's kids in 1872, so she may have been glad for a respite around Thanksgiving of that year. We don't know if the whole family went down to Roscoe Township, about 15 miles southeast of Cannon Falls, to visit Maria Sophia Ahlers, a sister of Alonzo's first wife Louisa, and her husband August Gottlieb Bucholtz, but their oldest child, Alice, was certainly there. Alice and her cousin Rose Bucholtz were about 14 years old, and Rose, one of the "young ladies of Roscoe", invited some boys to a "Leap year sleigh ride and party" on Thanksgiving Day. The adventure was reported in the Pine Island Journal: "The young people started from Mr. Hepners around 2 o'clock p.m and rode to Pine Island, remaining there just long enough to stock up with candy and sweetmeats and to get warm. Then returned to Mr. Hepners and arrived there about 9 o'clock. After supper the rest of the night was spent in playing games and having a good time generally. ... Our sleigh load will probably remember how just as they were nearing Roscoe on their way back from Pine Island the team became unmanageable, broke loose from the sleigh and lit out for home leaving the occupants wherever they happened to land. Mr. Hepner and Charlie Shiels accompanied the crowd as managers and teamsters. We arrived home about four o'clock the next morning."

Over in Red Wing at about this time, a young lawyer named Osee Matson Hall was setting up his first law practice. Born in Conneaut, Ohio on September 10, 1847, O.M. Hall graduated from Williams College in Williamstown, MA in 1868.

Probably no more than a couple of years after Hall's arrival, in about 1873, Ferdinand Kowitz and a partner started their first brewery, also in Red Wing. This may have been the "Bombach and Koke" brewery; in fact, the second name may actually have been "Kowitz".

Sadness visited the Jonathan Dibble household that year. On October 30, 1873, Jonathan's wife Ann died at about the age of 35. But a bit less than a year later, on August 30, 1874, Jonathan married Ann's 26-year-old sister, Sarah C. Smith (the "C" may have stood for "Cornelia"). Up until at least 1870, Sarah had been living at home with her parents Daniel and Olive Smith, who had moved back to Rising Sun from Kentucky. She was part of the Smith women's clothing business there; Olive was a tailor and Sarah and her sisters Alice and Luella were seamstresses. Sarah gave Jonathan a daughter named for her sister, Ann E Dibble, probably in April 1875.

We don't know what became of Jonathan's brother Alonzo's father-in-law Charles Ahlers. But his son (Alonzo's brother-in-law) Charles Ahlers Jr. had married Caroline Behrend, like him a native of Prussia, just a few years after their arrival, on October 18, 1857. Charles took up farming like his father, and the family lived in Roscoe Township in southeastern Goodhue County. Around 1860 they had a son, Edward, and in 1862 their daughter Amelia was born. A son, Henry, was born around 1863; he seems to have died young. Another boy, William, was born in 1865. Their second daughter, Louisia, was born in 1866, and their third daughter, Mary, arrived in 1868. By 1870 the family was living in Featherstone Township, just southwest of Red Wing, and west of Charles Sr.'s old stomping ground of Hay Creek, where their son Alford or Alfred Benjamin Ahlers was born, on June 9, 1870. Another boy, Lewis Alonzo Ahlers, was born on November 4, 1873. At some point after this, the family traveled to Texas, where they settled in the town of Graham, in Young County, about 100 miles northwest of Ft. Worth. Their last child, Charles J. Ahlers, was born there, on March 29, 1876. Then the family moved to Kansas, perhaps spending a brief period in what was then Indian Territory (now Oklahoma). The year 1880 found them in Kechi, Sedgwick County, KS, a suburb of Wichita.

By 1876 or so, the Coplin family had returned to Cannon Falls from yet another absence. Some time before 1875, the family moved to Worthington, Nobles County, MN, in the southwest corner of the state. From there they came to live in Northfield, another mill town on the Cannon River just ten miles west of Cannon Falls. (Northfield was founded by a member of the same North family that founded North's Landing and from which Jonathan's son Nathan got his middle name.) Not much later they returned to the latter city.

Ferdinand Kowitz's first brewery venture in Red Wing failed; competition in that town was fierce. Seeking a less crowded beer market, his family joined the stream of new arrivals to Cannon Falls at just about the same time as the Coplins returned. Ferdinand Kowitz is one of several Germans, and a very important person, in the direct line of this website's author. Our German ancestors and the Kowitz family deserve as much attention as those from Norway, and they will eventually have their own page on this website. For now, here's a brief sketch.

Ferdinand Julius Kowitz was born on July 4, 1842 in Prussia, to Erdmann G. Kowitz, a carpenter, and Christina Arendt. He had two brothers, August and Gustav, and three sisters, Caroline, Wilhelmine and Bertha, all born in Germany. The Kowitz family sailed from Hamburg and arrived in New York City in 1859; they settled first in Buffalo, NY. They migrated to Wisconsin in 1862; there is a story that Ferdinand, the oldest child, had been offered a job as brewmeister at G. Heileman's Brewery in LaCrosse. There he met Caroline Granke (born Christmas Day in 1845, probably also in Prussia) whom he married on September 13, 1864. Just a few months earlier, in April, his mother gave birth to another brother, Theodore.

Ferdinand and Caroline's first child, Ferdinand, Jr., was born on March 16, 1866. Their daughter Bertha was born in the LaCrosse suburb of Onalaska, WI, on February 14, 1869. Their second daughter, Edith, joined them on January 10, 1873, not long before the family moved to Red Wing. Their third daughter, Emma, was born there in July of 1876. Shortly thereafter, the Kowitz family moved once again, to Cannon Falls.

Ferdinand Sr. was something of a musician; he played the cornet. He was also a hard worker and resourceful businessman. Soon after his arrival in Cannon Falls, he established a brewery about a block north of the Cannon River on the village's North Side. (He may have taken over the brewery that was founded by Carl G. Mellin and Gerhard Brisman in 1868; that brewery was out of business by 1872. Or he may have started from scratch.) The Kowitz family home at 330 Cannon St. West was one of the first houses in that district. The North Side was expected by some eventually to become the main business district. Although that expectation never panned out, the area was conducive to the Kowitz Brewery, which eventually occupied a tract large enough for several buildings and a small hog farm.

Meanwhile, Jonathan Dibble, while maintaining his livery stable, embarked on a new venture. In those days, the US Post Office hired private contractors to handle overland transport of the mails. With a partner, fellow (former?) Mormon D.C. Stranahan, Jonathan purchased the delivery route from Red Wing to Northfield from previous owners Platt and Helstrom, and by early May 1876 he was in the mail business, which became something of a family tradition. Around this time his second wife, Sarah, became pregnant again. Later that summer, he took a trip "out west", and when he came back on July 29, the Beacon reported, "He informs us that the grasshoppers and farmers are both busily engaged harvesting what grain is left; the hoppers being a little ahead." This was the very same "grasshopper plague"--they were actually locusts--that Laura Ingalls Wilder recounted in On the Banks of Plum Creek, which took place at this time about 100 miles west of Cannon Falls, near Walnut Grove in Redwood County, MN. Then, in mid-February 1877--perhaps February 10--while the hoppers slept, Jonathan and Sarah's second child, also named Jonathan, was born.

Unfortunately, there was little time for these three people to get to know each other. Some six weeks later, Jonathan Sr. was suddenly taken ill and died within a few days, on March 23, 1877, at the age of 39. Cannon Falls residents were shocked; he had seemed to be in excellent health. His manner of death suggests a heart attack or stroke. Then, on August 7, baby Jonathan died. Sarah, and Jonathan's older children Nathan, Richard, Minnie and Daniel, along with Ann E, his daughter with Sarah, moved to Alonzo's farm. Sarah, understandably, may not have been up to providing much nurturing to the children for some time; family members later remembered that they were taken care of by Alonzo's wife Rebecca. Sadly, little Ann E herself passed away less than two years later, on January 17, 1879.

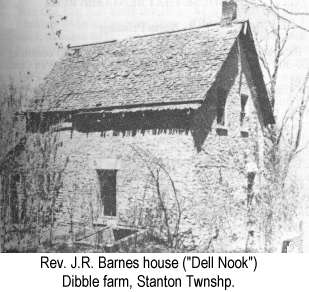

By 1877, Alonzo had purchased several tracts of land surrounding his and Jonathan's old claims (an "old settler" named John Hoffstatter and his wife sojourned on the latter for a few months in the late winter of that year), including that of the Reverend Jeremiah Root Barnes, minister of the First Congregational United Church of Christ where his wife Rebecca's father had served as deacon, whose ruined stone house on the land became known as "Dell Nook". According to the 1956 History of that church:

"Had the deep valley in which Mr. Barnes located his homestead been on the seashore it would have been called a cove. It was semicircular with a wide opening to the East, looking across to the hills opposite the new hamlet. As soon as possible Mr. Barnes began the quarrying of limestone from their own hill and, with only the help of his regularly employed man, built a house that still stands as sturdy as it was nearly one hundred years ago. Many men who lean to the fine arts have little ability in the manual arts, but Mr. Barnes was an exception. His building was not only sturdy and commodious, but he exhibited remarkable ingenuity in the contrivance of clipboards, closets, and storage space, things dear to the heart of every homemaker. Outdoors, too, he pleased his wife by leveling up the ground with a stone retaining wall and planting hardy lilies and wild rose bushes." As of 2021, those ruins seem to have disappeared; as best we can tell they were on land now owned by Harry Robinson, about 1500 feet northwest of the Dibble farmhouse on Oxford Mill Road.

In 1878 a new institution was founded in Cannon Falls, the First National Bank. Among its charter stockholders were both Alonzo Dibble and Ferdinand Kowitz.

And there was more evidence of the Kowitz family's prosperity. The brewery made deliveries by horse and wagon all over town, charging 90 cents a keg. In addition to the brewery, Ferdinand owned a saloon and a liquor store on 4th. Street downtown. His hog farm supplied pork for free luncheon sandwiches at the saloon. While this has been cited as a sign of Ferdinand's generosity of spirit, in fact it was common in the mid- and late 19th. century for cities to require saloons to provide a free lunch so customers would have something in their stomachs to soak up the alcohol. A better indication of generosity was the fact that he also provided free sandwiches to the brewery workers. Kowitz also chopped ice out of the Cannon River every winter, whether to keep his beer cool or to sell to the general public we don't know.

Ferdinand's and Caroline's son George Herman Kowitz was born on May 18, 1878. He was, for some reason, known as "Bismark". Their last child, Herman J Kowitz, was born on January 17, 1881. He was known, even more inexplicably, as "Napoleon". This childbirth was evidently too much for 36-year-old Caroline; she died two days later.

Meanwhile, young Peter S. Aslakson was proving to be an intellectually ambitious, and apparently very fast-learning, man. He was enrolled in the "Fourth" or freshman class at Carleton College in Northfield, Minnesota, about ten miles west of Cannon Falls, in the fall of 1875. Carleton, established in 1866, was highly unusual in that it admitted students of all races and both sexes, and did not bar women from any course of study or degree. Although the female students "reside[d] with the lady teachers, in a separate building", they intermixed freely with the male students in class and elsewhere. The institution was established by a group of Congregationalist churches and considered itself a "Christian college", but it did not promote any particular denomination, and the institution cited its Christian focus as the reason for its universal admissions policy. Peter was in the "English Course", a four-year course of study for students "unable to secure a thorough classical education". But he soon moved on from there to attend a "normal school" (teachers' college) and a business college in Keokuk, Iowa, while also taking a "full course in penmanship", and managed to graduate from the Iowa State University law school less than three years later, in 1878.

He returned home to his family's farm in Mineola Township, near Zumbrota in Goodhue County, and like many young lawyers on the make in those days, he started out as a schoolteacher, while also working a side job as a bookkeeper. He married Maren (Mary) Christina Ullevig, who lived in Hader, a village a couple miles west of the Aslakson farm, on May 7, 1879. Maren was born on February 25, 1860 in Lower Telemark, Norway; she came with her father Johannes Johannesen Ullevig and the rest of her family to the United States in 1862. Their first child, Laura Matilda Aslakson, was born on November 20, 1879.

By now, Cannon Falls and Goodhue County were looking less like the frontier and more like middle America. The county's leaders were exceptionally proud of their school system. The 1878 county history states, "No interest is dearer to the hearts of the people of the American Republic than the free school system. To make war on that system would be to make war on the life of the nation." Alonzo's daughter Sarah certainly agreed with that sentiment. She taught in the Cannon Falls schools beginning in the late 1870s. While still living on the farm, she would walk into town to teach, and also on Sundays to play the piano at services at the Episcopal Church of the Redeemer. She was probably present at the 1880 Graduating Exercises, where Ella Coplin performed "Now I Lay Me Down to Sleep" with three other girls. There were just two graduates that year, and they were far outnumbered by the students who participated in the program.

Farther north and west, though, life remained raw and uncertain, and tough immigrants still struggled to dig a living out of the tough prairie sod.

.png)

.png)

Dibble-captioned.png)

Dibble-captioned.png)

Dibble & daughter Ann E.-captioned.png)

-captioned.png)

.png)