The Norwegian Kommune (municipality) of Våler sits astride the Glomma River in what was, in the nineteenth century, Hedmark County, about 40 miles northeast of Norway's capital city, Oslo. It lies some 15 miles west of the Swedish border in the Finnskogen, the "Forest of the Finns", one of the most heavily wooded regions of the country, and the land is rolling and dotted with hundreds of small and medium-sized lakes. Våler was allegedly founded by St. Olaf, an ancient Norse king, who settled a dispute among the earliest Christians about where to build their church by shooting an arrow into the air. The arrow landed in a Vål, a rough newly-cleared area in the woods, still dotted with burned tree stumps, on the east bank of the Glomma. Nearby is a spring that, according to legend, St. Olaf invested with miraculous healing powers. Våler is the plural form for such geographical features, and you can imagine that many places could have merited that name through the centuries. There are, in fact, several other Vålers in Norway. "Our" Våler municipality is about the size of Nassau County, New York, or just a bit larger than Indiana's Tipton County. Within it there is a village called Våler, and Våler is also the name of the local Lutheran church parish. In earlier times the parish was the governmental administrative unit, but that is not true today. There isn't much difference between the borders of Våler Kommune and Våler parish, though, so we can use the two interchangeably.

Near the end of the eighteenth century, Peder Eriksen owned and farmed a parcel of land, a bruk, called Tronstuen, that was part of the Aslakrud gaard, or farm, in Våler parish about a mile and a half west of the Glomma and about ten miles northwest of Våler village, not far from the modern town of Braskereidfoss. We can't be more specific about the location of that parcel because it can no longer be found by that name, or by its designated number, on modern maps. Peder was born in around 1758. He married a woman named Olea Pedersdatter, born in about 1769; her parents may have been Peder Larsen and Dordi Embretsdatter. Small farmers in those days, even when they owned the land, were usually fairly poor. Peder's house would likely have begun as a log cabin, perhaps with a sod roof, on a rubble-stone foundation. It may have had a loft for sleeping, and as time went on and the farm became a bit more prosperous, he may have added a wood-frame section sided with vertical rough-sawn boards. Peder and Olea's son Embret Pedersen was born in around 1791 at Tronstuen. Embret's brother Peder Pedersen was born there in around 1799.

Embret grew up on the farm and married Marthe Olsdatter. He likely inherited the Tronstuen property, and his and Marthe's son Enok Embretsen was born there on May 16, 1831.

Enok Embretsen left his parents' home and went to work on the Ommundrud bruk, perhaps as early as 1846. It was common enough for boys to go to work for a different farmer at the age of 15, and sometimes even a first-born son like Enok, who, by both law and custom, would inherit his father's land, did this. He was living at Ommundrud, perhaps half a mile north of his parents, when he and Anna Maria Olsdatter were married on April 10, 1855 in the Våler church. Anna was probably born in 1831 about 12 miles southeast of Ommundrud on a bruk called Svarthagamangen that was then part of a large farm called Sjøli in neighboring Åsnes parish. Although at times he farmed, and eventually owned land, Enok was primarily a carpenter, and he moved around a lot, plying his trade on different farms throughout Våler parish.

The first son of Enok Embretsen and Anna Maria Olsdatter, Embret Enoksen, was born on August 29, 1855, at Nordli. Nordli was a bruk attached to the Svenkerud farm, located about 2 miles north of Ommundrud. By June 11, 1861, when their second child, Olea Enoksdatter, was born, the family was about 7 miles further south, at the Sagmoen bruk, part of the Sæter farm, just across the river from the village of Våler. The family moved again, this time to a bruk called Sandmoen on the huge Braskerud farm, where their daughter Christiane Enoksdatter was born on May 21, 1864. The location of that bruk is not completely certain. The name is given as "Sandmoen" in Christiane's birth record, but there were four bruks with "Sandmoen" in their names in Braskerud at that time: Nedre ("lower") Sandmoen, Øvre ("upper") Sandmoen, Sandmoen skog ("forest"), and just plain Sandmoen. The parcel that was just plain Sandmoen in the 1860s no longer appears on maps, but the parcel then called Nedre Sandmoen does appear as just "Sandmoen" on the map today. The two bruks are about 4 miles apart.

At any rate, it wasn't long before Enok's and Anna Maria's family moved again, to a bruk called Morud. We know exactly where that is, and it's just south of today's Sandmoen. The farm is on the north side of a gravel road called Engevegen, about 170 yards east of that road's intersection with the Bronkavegen (vegen means "road"), about a third of a mile west of the Glomma River and some 2 miles northwest of Braskereidfoss. In the 1865 census, Enok was a husman med Jord, a "cotter" or sharecropper at Morud, likely working on a rent-to-own arrangement, and at that time Morud belonged to the Svenkerud farm. By December 14, 1869, when Enok's and Anna Maria's second son, Ole Enoksen, was born, Enok owned the bruk, though it was still listed as part of Svenkerud. Today it's part of Braskerud.

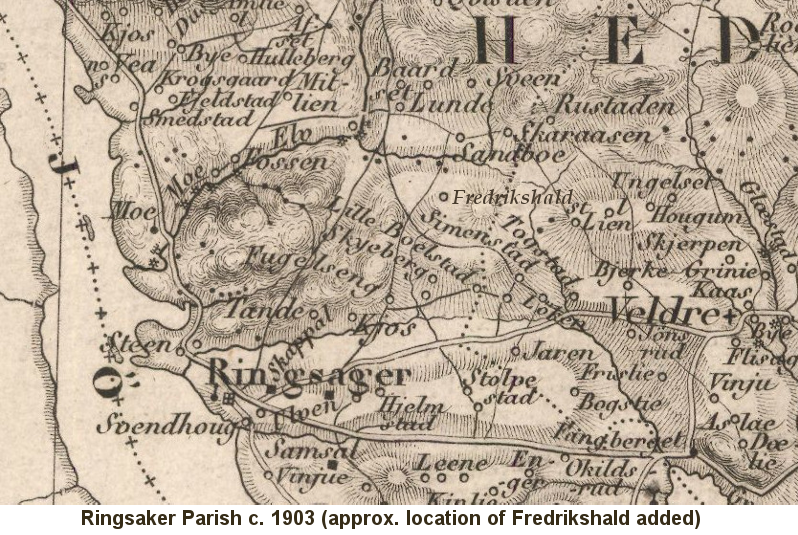

Roughly 40 miles to the northwest of Våler parish, the Ringsaker parish town of Moelv lies along Mjosa Lake, a wide spot in the Lagen River. Also in Hedmark County, the area is about 10 miles southeast of the Olympic site of Lillehammer and some 40 miles due north of Oslo. Ringsaker parish is about the size of Genesee County in NY, and a bit smaller than Marin County, California. About a mile south of Moelv stands the Ringsaker Church, named for the nearby Ringsaker Farm, which is also still there. (It's been suggested that "Ringsaker" refers to the Norse god Ullr and can be translated as "Lord of the Ring Field".) The eastern portion of the parish generally slopes downward toward the lake, and in the early 19th century was mostly covered with pine forests out of which farmland had been cleared.

About 13 miles northwest of Moelv lies the farm of Nedre ("lower") Alm. On one of its bruks, a child named Johannes Pedersen was born in October 1816. His father, Peder Pedersen, may have been born in 1782 and, as a teeenager, lived on the adjacent farm of Øvre ("upper") Alm.

Johannes moved to a farm called Kroksgaard (sometimes spelled "Krogsgaard") at some point, about 12 miles southeast of Nedre Alm, and only about a mile and a half north of Moelv. That's where he was living when he married Kjersti Larsdatter on December 29, 1840 in the Ringsaker church. Kjersti's parents were Lars Pedersen and Gjøa Hansdatter. She was born on November 18, 1814, possibly on a bruk called Lunde Søndre, about 27 miles southwest of Kroksgaard in neighboring Oppland County, or perhaps much closer, on a farm called Sørlunden.

Johannes and Kjersti had moved less than half a mile to a farm called Fjeldstad by November 18, 1842, where their son Lars Johannesen was born.

Several years later, on May 26, 1849, Johannes and Kjersti had another son, Mathias, who was called "Mat". We don't know where he was born, but by 1857 the family had moved again, either to Fredrikshaab, a farm about seven miles north of Alm, or to Holla, some four miles southeast of Nedre Fjelstad, where Lars was confirmed on October 11 of that year.

Certainly by June of 1862 Johannes and his family were at Holla. At least, that's the name the locals knew it by. In the official church records it was called "Fredrichshald" or "Fredrikshald".

"Holla" (also spelled "Halla" or "Halle") comes from old Norse "hallr" or "hǫll", meaning a hill, rise or slope. In the Danish and Norwegian languages derived from old Norse, the word is "hallen" or "halden". There are many places in Norway called "Holla", as you would expect for such a generic name. Because land has been transferred back and forth between different farms, and the farm names and numbering system have also changed a few times, today we can't definitively identify where this particular Holla was. As best we can tell, it lay within an area roughly 2 miles north to south and 2/3 mile east to west, situated about four miles east of Moelv and about the same distance southeast of Nedre Fjelstad. The farm was in existence at least as early as 1816, when taxes were paid on it. It may have included several bruks, only one of which was at first rented, and later owned, by Johannes Pedersen.

So how did this mundanely-named place become lordly "Fredrikshald"? The short answer is, we're not sure. The long answer is an educated guess. Some 200 miles south, near Oslo, in today's Viken County, was a community called Halle or Halden, and during the 17th century, when Norway was owned by Denmark, its brave citizens fought off several Swedish attacks. In return, the Danish king, Fredrik III, granted the place "city privileges" and renamed it "Fredrikshald" in 1665. This event became a matter of considerable patriotic pride for Norwegians, and was celebrated down through the years. That 1816 tax record for Holla in Ringsaker referred to the place as "Fredrikshald". However, it seems that nobody in that neighborhood called it that in ordinary conversation; the name only appears in records--not just tax records, but census records and vital records for our family. Why that should be is unknown, but the best explanation is that the local folks knew their history and they wrote down "Fredrikshald" because they thought it sounded more prestigious than just "hill".

As for how Johannes Pedersen and his family came to be living on this august estate, the guesswork is quite a bit simpler. Johannes eventually did acquire ownership of the land. His wife Kjersti Larsdatter was baptized there much earlier, in 1828. We don't know whether her father Lars Pedersen was the owner or a renter at that point, and we don't have further records on this family to show whether Kjersti had any male siblings. But it seems quite possible that Lars became the owner of Holla/Fredrikshald and he did not have any male heirs, so his son-in-law Johannes inherited the bruk from him.

Johannes' son Lars didn't have much interest in farming, and as a young man he studied music intensively, learning to play the organ, violin and guitar, and he became a good singer. That was no way to make a living though, so he also learned the carpentry trade, and during the winters he worked as a bread baker. Like most young Norwegian men, he was drafted into the army, and on June 10, 1862, at the age of 19, he left his home at Holla, which he called "Fredrikshald" in his internal migration record, and moved to Christiania, the capital of Danish Norway (now called Oslo), probably to begin his military service. There were, no doubt, hundreds of men named Lars Johannesen in that city, so Lars needed to choose a surname to distinguish himself. We don't know for sure, but it seems plausible that he chose "Halden" at that time. It's a perfectly fine choice; in fact, in 1928 the famous Viken County Fredrikshald changed its own name to Halden.

The River Flisa flows southwest into the Glomma in Åsnes parish, Hedmark County, about 20 miles southeast of the Morud farm. Åsnes is about the size of New York's Montgomery County, and a bit larger than Clear Creek County in Colorado. From time immemorial, a waterfall called Libergfoss tumbled and sparkled about seven miles up the Flisa from its junction with the Glomma. As elsewhere, waterfalls in Norway, with their strong flowing energy, were considered good sites for mills, and in 1770, a cowherd named Jon Embretsen built a mill there. That mill burned in 1800, but it was rebuilt, and registered as "Libergfossen" in 1802, probably by Knut Eliassen of Sakserud, who was later known as Knut Eliassen Liberg. He seems to have had a daughter, Kari Knutsdatter, who married Peder Olsen on October 25, 1804 in Grue parish, about 15 miles southwest of the mill, where she was living at the time. She may have been born there on August 25, 1777. Peder was a miller himself, working for the huge gaard of Sønsterud whose many bruks lay on both sides of the Flisa.

Peder and Kari had at least three children: Ole Pedersen, born, probably, on December 2, 1808 (who may have become a schoolteacher), Erik Pedersen, probably born on February 8, 1810, and Peder Pedersen, born on January 5, 1815, at Libergfossen. When the younger Peder was confirmed, on September 19, 1830, the mill was known as Sønsterudkvern.

Kvern is Norwegian for "grinder" or "millstone", and is often used to refer to a mill, even though the Norwegian word for mill is mølle. We aren't sure how the place name was changed, but a good guess is that Libergfossen became part of the Sønsterud gaard and was then referred to as the Sønsterud mill.

Young Peder Pedersen married Hellene Andersdatter of Knappom on July 19, 1839. Knappom is another big gaard, with bruks just a bit east of Libergfossen/Sønsterudkvern, on the other side of the Flisa. We don't know which bruk Hellene came from. She was born on May 6, 1818. Her parents were Anders Tostensen, probably born on February 3, 1782, and Marthe Eriksdatter.

Peder Pedersen and Hellene Andersdatter had many children, one of whom was Anna Marie Pedersdatter, who came into the world on December 16, 1842, just about one month after Lars Johannesen of Fredrikshald was born. The others were:

Karen Pedersdatter, born around 1839

Peder Pedersen, born around 1844

Arne Pedersen, born May 3, 1846

Eberhard Pedersen, born around 1848

Pernille Pedersdatter, born February 4 or 5, 1851

Knud Pedersen, born around 1853

Ole Pedersen, born around 1856

Hannah Christine Pedersdatter, born around 1858

Martin Pedersen, born around 1860

By the time of the 1865 census, this large family were all living together on Sønsterudkvern, which Peder Pedersen was renting. The oldest child, Karen, had married a tailor named Johan Jacobsen (born about 1836), and they had two sons, Jacob Johanesen, born about 1861, and Peder Johanesen, born about 1863. The others were all single. Peder Pedersen, Arne Pedersen, and Eberhard Pedersen were all lumberjacks. That suggests they weren't working for the mill, because it was a gristmill that ground grain into flour, not a sawmill. In later years millworkers recalled that working around the mill was dangerous; it would be easy to get caught up and mangled or crushed in the various belts and pulleys that transformed the downward energy of falling water to the rotational energy required to grind two huge horizontal millstones against each other. It was also messy, as the horses that pulled wagonloads of grain and flour to and from the mill left little piles all over the ground. On the other hand, the job apparently came with a free lunch; the millers told how they ate "hot flour fresh from the grindstone".

A bit over 200 miles southeast of that part of Norway lies the Swedish county of Jonkoping. There, somewhere just west of Lake Ralangen, between the town of Aneby and the little church crossroads at Lommaryd, Johan Peter Johannesson was born, on March 30, 1833. Although the landscape is an attractive patchwork of forests, fields, and lakes, the farmers who lived here had a hard time of it; the soil is a sandy, rocky mixture that did not produce well before the introduction of modern farming methods and fertilizers.

Sweden, like the rest of Scandinavia, was a Lutheran country, and until the mid-1800s its citizens were forbidden to practice any other religion. Those who did faced severe repression. Even when things began to be liberalized after 1850, Catholic Swedes, a tiny minority, were still forced to remain members of the Lutheran church.

Johan may have married a woman known as "Stina" (short for "Kristina") in February 1860, though they may not have had any children early on. Many of Johan's neighbors, facing lives of grinding poverty, were emigrating to Minnesota, and in 1870 he and his wife joined them. Perhaps, as Catholics, they also hoped to be free of interference with their practice of religion in the new land.

Meanwhile, back in Ringsaker, Norway, Lars Johannesen's family had also been hearing wonderful things about Minnesota, where some of their friends had taken homesteads after the Homestead Act, which, unlike earlier American land settlement acts, did not require a cash payment for land, was passed in 1862. Lars may have heard the same tales in the army. In any case, when he got back home the family was buzzing about the new opportunity, including Johannes who, though by this time the owner of Fredrikshald and not just a tenant, must have felt that things would be better for his children in America. So they saved their money and booked passage in the early spring of 1866.

They did their homework and were prepared with food and equipment, bringing with them dried beef, dried smoked herring, butter, cheese, dried peas and beans, flour, sugar, vinegar, dried flat bread, a keg of sour milk and even a barrel of water. They loaded chests with clothing and bedding, soap, and a "'fine comb' as they would be sure to get lice on the boat." They brought Lars' carpenter tools, axes, scythe, a muzzle-loading shotgun, pots and pans, dishes, silver, lamps, Bibles, hymnbooks, music books, and a spinning wheel and wool carders.

On board the boat, Lars met Anna Marie Pedersdatter. She was traveling alone, but as she and Lars became friends, she decided to accompany his family to wherever they ended up.

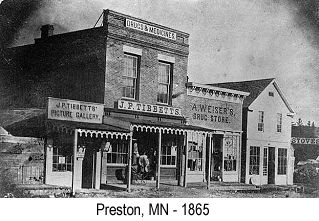

Lars Pedersen and his family, along with Anna Marie, arrived first in New York City. Lars and kin were all of Fredrikshald, but it's likely they gave the name "Halden" to the immigration officials at this time (as we mentioned, Lars may have chosen the name earlier). Anna Marie, of Sønsterudkvern, may have shortened her previous residence name to "Kvern" at that time as well. They traveled across the country together to join friends in Fillmore County, Minnesota. At the land office in Preston, they learned that there was no more unclaimed land in the area. They resolved to claim land farther north, but first they needed to raise some money. Lars and Anna worked together for the same farmer, for 50 cents a day apiece plus room and board. A temporary stop became a four-year sojourn. Lars and Anna were married on October 8, 1866 in the Union Prarie Lutheran Church. (Actually, the marriage was likely performed in the home of Ole Embretson. The church had just been founded the year before by Norwegian immigrants. The founders bought a two-acre lot about halfway between Preston and what later became Lanesboro, but did not erect a building until 1869.) Lars' and Anna's daughter Caroline was born on July 5, 1867, in or near Preston. That town is ten miles north of the Iowa border and only about 65 miles southeast of Sogn, where at that time Jonathan and Ann Dibble were working their farm and getting to know their new infant daughter, Minnie.

Time passed. Lars' mother Kjersti became ill and died. Lars and Anna worked hard and acquired a plow, wagon, oxen, a cow and other things they would need for their new farm. After the harvest in 1868, Lars and Mat took a trip northwest to look for land, first taking the train to Alexandria and then walking north about 50 miles to where they had heard claims could be had. They found an attractive region of lakes, woods, and rolling hills near where the town of Fergus Falls would later be founded. The brothers walked back to Alexandria, and filed claims for Lars and for their father Johannes (Mat, at age 19, was too young to stake a claim).

The following spring, the Haldens joined several other families from Fillmore County in a wagon train headed north. The trip of about 225 miles took several weeks at the slow pace of the oxen that drew the wagons. The women would hang buckets filled with dirty laundry, water and soap under the wagons as they traveled, and the jouncing motion washed the clothes for them. Then they discovered they could churn cream into butter the same way. The bouncing motion did not seem to bother Anna, even though for at least part of the trip she was in "a family way".

As the family historian reported, "After reaching the St. Paul area, for a time they could follow the trail where the Red River ox carts had gone, but the last part of the journey was virgin land. There were many lakes to skirt around, and rivers to cross, so picking their way was not easy. At night they formed a circle with their wagons, tethered the cattle and oxen to graze, and proceeded to feed their families and rest for the night. One man was always on guard. However, they had no trouble with the Indians, in fact they did not even see very many of them. After milking, they often made a milk soup with barley or oatmeal in it, or made a porridge for their supper. Game was plentiful so they sometimes had duck, prairie chicken or rabbit to eat."

In the second week of July, Lars and his family arrived on their claim on the eastern edge of Fergus Township, about 3.5 miles northeast of where Fergus Falls is today. His neighbor Ole Jorgens, who settled a few miles southeast of Lars near Wall Lake in Aurdal Township, reported that there were only a handful of white families there at the time.

Lars claimed 160 acres (the south half of the northwest quarter, and the south half of the northeast quarter, of Section 24) just west of the location reserved for Aurdal School No. 80. There was a large pond on the southern boundary of the claim. Today, the Canine Acres dog boarding center (24663 County Hwy. 111, Fergus Falls, MN) occupies part of this land. Lars's father Johannes also claimed 160 acres, just southwest of Lars's land. This upside-down-L-shaped parcel included the northwest quarter of the southwest quarter of Section 24 (just south of Lars), the eastern half of the southwest quarter of Section 23, and the northeast quarter of the northeast quarter of Section 26. This area contains numerous springs, creeks, and ponds which have expanded and contracted over time. Lars's pond is still there today, but a larger lake (possibly known as "Webber Lake") that bordered Johannes' claim on the northwest corner has shrunken to half its size. Mathias likely lived with Johannes on that claim and helped him work the land.

The group of settlers worked together to plow the ground and plant wheat, potatoes, turnips, carrots and cabbage, and build their log cabins and stables for the livestock. The crops grew exceptionally well, and the farmers worked hard to clear and break up more land for the next year's planting. That winter, on January 10, 1870, Lars and Anna's daughter Eline was born. She was the first white child born in the township.

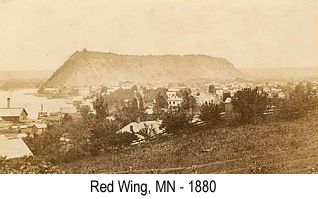

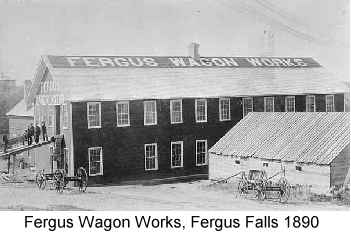

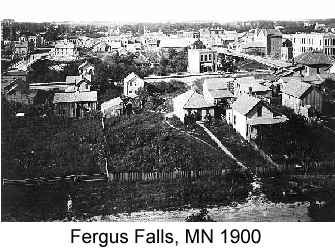

Later that year a Minneapolis real estate speculator named Burdick bought land along the Ottertail River near the falls, which had been named for a man who had financed an exploration trip to the region 15 years earlier. Burdick began promoting the area and selling land to settlers. In 1872 the town of Fergus Falls was incorporated. The new town already had two bridges across the river, a flour mill, a bank, two general stores, several churches, one doctor, and eight lawyers. Perhaps the heavy legal presence is what led the town to be designated the county seat that same year.

Time passed and, despite all the lawyers, the little band of Norwegian settlers prospered and grew. Anna's brother Arne Pedersen arrived in the US in around 1870. He lived in or near Northfield, in Rice County, MN about 5 miles west of Alonzo Dibble's farm in Goodhue County, for a while, and also did some contruction work in and around St. Cloud, and he took an 80-acre claim in Lake Andrews Township, Kandiyohi County, about 40 miles southwest of that city, before finally coming to the Fergus Falls area. By 1880 he was living with Lars and Anna Marie Halden and their family. He eventually purchased his own farm there, and also did construction work on the side. He did not immediately take the name "Kvern"; instead he went by "Pedersen" or "Peterson" for several years, and when he finally changed to Kvern, he said it was because "Der vass yoost too many damn Pedersens!"

On March 18, 1872, Lars and Anna Halden's second child, John Georg Halden, was born. He was baptized on May 9 of that year. Sadly, he died just a few months later, on December 12. Lars and Anna buried him on a little rise in the southeast corner of their claim that became the Kongsberg Cemetery. In the following year, their third son, Peter Halden, was born, on November 11. He was followed on February 16, 1876 by Inga; a second son named John (with middle initial L this time), on May 20, 1878; a son Martin born in about 1882; a son Oscar born November 16, 1883; and a son Alfred born on February 5, 1887.

Some time before 1875, Lars' father Johannes remarried to a woman named Inga. Twenty years younger than her husband, Inga was born around 1838 in Norway. By 1884, Mathias officially owned Johannes' farm.

Mathias married Mina Mikkelsdatter Braaten on September 29, 1877. Mina was born on March 4, 1859 in Hamar parish, Hedmark County, Norway, which is, roughly speaking, about ten miles east of the Morud bruk. Not surprisingly considering her patronymic, her father's name was Mikkel (Michael) Braaten, and the family may have been related to E. A. Braaten, who owned quite a bit of land around Spring Lake in south-central Aurdal Township in the 1880s. Their son John Alfred Halden was born on December 17, 1878 on the farm in Fergus Falls Township. Their second son, Karl Mathias Halden, was born on April 9, 1880. A daughter, Ida Mathilde Halden, was born on November 11, 1881. A third son, Leonard M. Halden, was born on February 13, 1884, and their last child, Emma Louise (or Louise Emma) Halden, was born on January 14, 1891.

Arne P. Kvern married the much younger Olina Haugen from over in Aurdal Township in around 1883. Olina was born February 22, 1866 in Faribault, Rice County, Minnesota. Her parents were Halvor O. Haugen, born around 1832, and his wife Karen, born around 1834, both in Norway. The Haugens had 160 acres in Section 21 (the northwest quarter) of Aurdal Township in 1884, but Arne may have met Olina as a little girl when he was living in Rice County in the 1870s. Arne and Olina's first child was Paul Kvern, born April 26, 1885. They had a son Helmer H. Kvern on March 22, 1887, and they may have had a daughter named Ella A. Kvern in November 1889.

Arne's sister Pernille Pedersdatter came to the United States in 1880. She considerately brought her husband, Eberhard Olsen, along with her. They sailed from Oslo on April 30, and arrived some time in May of that year. The couple had been married in 1879 in Norway, and their first child, Olava Eberhardsdatter, was born there in that year. Eberhard was born in 1853; in 1875 he and his parents Ole Olsen, a land-owner and logger who was born in 1819 in Åsnes and Gunnild Syversdatter, born in 1826, also in Åsnes, were living on one of the Ingelsrud gaards (there were two: Ingelsrud store ("big") and Ingelsrud lille ("little"), each with several bruks), about a mile or so southwest of Sønsterudkvern. Thus he was known as Eberhard Olsen Ingelsrud back in the old country, but the couple chose to adopt his patronymic as their surname, and Americanize its spelling, when they came to America. Pernille and Eberhard went first to the Fergus Falls area, where they probably stayed with her sister Anna Marie and Lars Halden, along with her brother Arne, who was also staying with the Haldens. There, on November 17, 1881, Paul Olson became their first child born in the United States. In 1884 they purchased a farm in Erdahl Township, Grant County, MN, about 25 miles southeast of Fergus Falls. In 1900 this farm consisted of 240 acres comprising the south half of the northwest quarter, and the southwest quarter, of Section 22, some three miles south of the Erdahl post office.

Pernille and Eberhard Olson had several other children in Grant County:

George Olson, born November 26, 1884

Edward Vernon Olson, borh February 12, 1888

Elise Paula Olson, born August 15, 1890

Selma Olson, born December 28, 1893

Emma Olson, born April 1, 1896

The Fergus Falls settlers were also busy in other ways. They built a log schoolhouse, perhaps just southeast of Lars' claim on the other side of the Aurdal Township line (where School No. 80 appeared on a later plat map). They also established a Lutheran congregation in 1872, known as the Kongsberg Church, which met in Lars' home for many years. They didn't get around to building a church until 1886; it may well have stood next to the cemetery. But it didn't have a steeple because none of the settlers understood the complex geometry and trigonometry required to build one.

Meanwhile, down in Goodhue County, the Swedish immigrant Johan Peter Johannesson (now known as John P. Johnson) and his wife Sarah had settled in what was then Grant Township in around 1870. Its name was changed to Welch in 1872 to honor Major Abraham Edwards (or Edward) Welch, of Red Wing, who died in the Civil War. The township is notable for its many "Indian mounds", the remains of towns, forts, and ceremonial locations built along the Cannon River by a considerable population of Native Americans before the "Great Dying". Coincidentally, its first white inhabitant's name may also have been Johnson--the Methodist Episcopal minister J. C. Johnson, who settled there in 1855. That Johnson reported that there were still many Dakota people in the area at that time.

Welch Township is at the northern tip of the county, between Cannon Falls and Red Wing. It contains the little hamlet of Welch, on the Cannon River on its southern border. We don't know if John owned or rented his farm in the township, but in 1870 he and his family would have lived perhaps 15 miles, as the crow flies, northeast of Jonathan Dibble's prosperous Warsaw Township spread.

John and Sarah Johnson had at least four children:

Mary Johnson, born in 1873 or 1874

Hannah Johnson, born August 30, 1875 in Welch

Charles Johnson, born around 1877

Francis Alfred Johnson, born March 2, 1880, in Welch

Back in Norway, the young Ole Enoksen of Morud, like Lars Halden, had learned carpentry skills, as well as shoemaking. But he was the younger son and did not stand to inherit his father's farm. He was also facing compulsory military service when he turned 21, so he decided that he had a better future in America. On a spring day in the early 1890s, he packed up his prized chest of carpenter tools, and with his friend Ben Sonstrud, he took ship for the United States.

At first they joined friends in Reynolds, North Dakota. Reynolds is about 12 miles south of Grand Forks, ND, and some 35 miles south-southwest of Warren, MN. Perhaps Ole's friend Ben was related to Olaf Sonsterud, who owned the land on which the town of Reynolds was established. (We might guess that both of them came from the Sønsterud farm on the River Flisa, but unfortunately, and as is often the case in Norway, there were several other locations, including gaards and bruks, with that name widely scattered through that country.) Olaf sold the land to the St. Paul, Minneapolis & Manitoba Railroad in 1880. The town was named for Dr. Henry A. Reynolds, a Civil War surgeon from Maine. He and others filed claims in the area, and we assume the railroad donated some of the land for the town, since having towns to which passengers and freight would travel was in their interest. Dr. Reynolds laid out the original town plat, and in 1881 he was appointed its Postmaster.

Many of the earliest settlers of Reynolds were Germans and Norwegians; they had to communicate with each other by means of gestures and sketches. The first edition of the local paper, the Reynolds Enterprise, published October 2, 1891, contained this plea: "NORWEGIAN SPEAKING CITIZENS: If you cannot read an American paper yourselves, don't keep your children in ignorance of what is going on around them, but let them have the Enterprise and read the news in their own American language ... taught them in the public schools..." We may wonder how the non-English-reading Norwegians got this message, but the editor seems to have understood marketing.

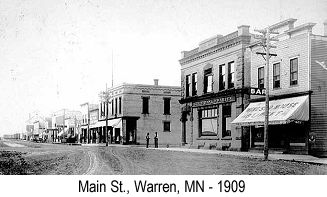

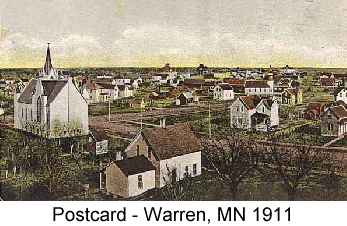

Ole and Ben worked as carpenters and kept an eye out for available land. They learned that unclaimed ground was available east of Warren, Minnesota, about 15 miles northeast of Grand Forks, and only about 35 miles from the Canadian border. So they journeyed to the nearest US Land Office, at Crookston, to inquire. From there they walked about 30 miles north to check out the area. They met some fellow countrymen on their hike who urged Ole and Ben to settle near them. The land was flat and mostly treeless, and there were fewer lakes in this part of the "Land of 10,000 Lakes" than in the Våler region of Norway. We don't know if this cold, empty place reminded Ole of home.

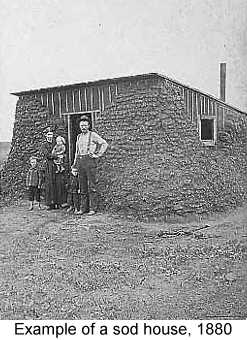

Ole claimed the southeast quarter of Section 14, 160 acres. As so many settlers on the Great Plains did, he built a house of big blocks of tough prairie sod. The house was probably pretty close to the farmhouse and barn that today stand at 22052 190th. St. NW in Helgeland Township. As Ole's daughter later described it, "The walls were quite thick, so it would be fairly warm in winter. It had a small window on each side and a wooden door. There was a vein of white sand nearby, so after he smoothed the walls on the inside, he made a wash of the white sand to make it lighter inside. He pounded pegs into the walls to hang things on, such as the heavy iron kettle and frying pan which was called 'a spider'. He made a carpenter's bench, which he knew he would need later. This he turned upside down and filled it with shavings and hay, which he used for a bed."

Ole worked cooperatively with his neighbors, trading labor for the loan of oxen and a plow; trading firewood for the use of a sleigh to haul it from the nearest woods, eight miles away. Slowly he dug a garden, grain fields, and livestock pasture out of the virgin soil.

During the winter he visited his cousins who lived near Fergus Falls, about 115 miles south southeast of Warren. While there, he did a little carpentry, and met the Halden family. We will return there in due time.

Meanwhile, back in the old country:

Ole's brother Embret Enoksen married Christiane Knudsdatter (born in 1851), whose father Knud Einarsen rented one of the bruks that belonged to the huge Skarderud gaard on the east side of the Glomma, on November 23, 1877. They had daughters Gustava Embretsdatter, born in 1881, and Anna Embretsdatter, born in 1885. By 1891 Embret was renting a bruk called Godaker, part of the Killingrud gaard, located about a half mile south of Morud.

Although Embret's father Enok Embretsen had been listed in vital records as the owner of Morud as early as 1869, it wasn't until December 7, 1892 that the deed was formally transferred to him from Gunnerius Knudsen. Enok lived until at least 1900. His wife Anne Marie Olsdatter passed away earlier, on May 16, 1893. Embret inherited the bruk and left Godaker behind. He died at Morud on September 12, 1936.

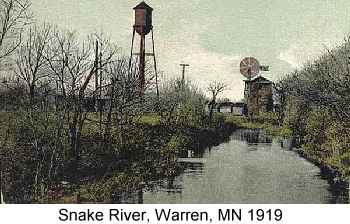

The Sønsterudkvern mill continued to grind grain, hauled by horse-drawn wagons, into flour, well into the 20th century. Around the turn of that century it seems to have added turbines to generate electricity. It was demolished in the late 1960s, and nothing is visible there today except the millrace that once delivered rushing water to its machinery.

Our Scandinavian families prospered and grew quickly, as did our other ancestors, in the fertile ground of the Upper Midwest of the United States, and that is where we will find them next.

- captioned.png)

- captioned.png)

- captioned.png)